“He could,” Jane commented slowly, “have simply hit his head on something while unloading those packages from the carriage. There might be as simple an explanation as that.”

“Then why all the subterfuge? Why hide him in the ballroom and then whisk him away again?” A breeze whipped Amy’s dark curls into her face and she hastily pushed them out of her way.

“He could have felt better and left.”

“Really, Jane!” The warmth had departed with the sun, and Amy shuddered in the twilight chill, feeling the evening breeze pierce the thin fabric of her frock. “Can you really believe that?”

Jane leaned briefly against Aphrodite, looking perturbed. She finally straightened up and made a face at Amy. “No, I can’t. Come with me and I’ll show you why.”

Amy hurried with her cousin back to the ballroom, where Jane paused just within the entrance.

“Yes?” Amy prompted Jane, who had a regrettable habit of thinking things through before acting on them.

“Look at this.” Jane indicated the door.

“It’s dirty?”

“That’s just it. It’s too dirty. It looks like someone deliberately took garden dirt and smeared it along the glass. See? Here and here? It’s too thick and too uniform to be merely dust and age. It’s as if. . .”

“. . . someone didn’t want anyone seeing in!” Amy finished for her excitedly. Jane quickly moved the candles aside as Amy leaned in to peer at the dirt on the doors, her short curls swinging recklessly close to the flames.

Jane nodded. “That’s just it. But why? What does Edouard have to hide?”

Amy shut the door with a decisive click, and beamed at her cousin. “But, Jane, that’s obvious. Don’t you see? It’s proof that he’s in league with the Purple Gentian!”

The Purple Gentian swung down from his carriage in the courtyard of his own modest bachelor residence—only five bedrooms and a small staff of ten servants, not counting his valet, cook, and coachman—with a heartfelt sigh of relief.

“Zounds, Geoff, it’s good to be back,” he announced to the slender man in waistcoat and shirtsleeves who waited by the door.

“After your dangerous mission into the heart of London society?” his second-oldest friend responded with the quiet humor that had drawn Geoff into Richard and Miles’s circle at Eton.

“Don’t mock,” Richard chided, pulling off his hat and scrubbing one hand through his hair. “I only just made it out of there alive.”

Having displayed their decades of affection by a brisk handshake, Richard surged into the foyer and began dropping his hat, cloak, and gloves on any surfaces that presented themselves. His butler, Stiles, cast his eyes up to the ceiling as he followed in Richard’s wake, gathering up gloves from the floor, cloak from a chair, and hat from the doorknob.

“Will that be all, my lord?” Stiles inquired in the afflicted tones of King Lear.

“Could you see what Cook can rummage up for me? I’m famished.”

“As you wish, my lord,” Stiles intoned, looking, if possible, even more pained than before, and hobbled his way out in the direction of the kitchen.

“He does make a convincing octogenarian,” Richard commented to Geoff as they headed for the dining room in the optimistic anticipation that food would rapidly be forthcoming. “Hell, if I didn’t know better, I would be fooled.”

Geoff darted into the study and emerged shuffling a stack of papers. “You’re not the only one he’s fooled. I gave him last Saturday off, thinking he would wash the gray out of his hair, do the rounds of the taverns, what have you. Instead, he pulled up a chair before the kitchen fire, threw an afghan around his shoulders, and complained about his lumbago.”

The two friends exchanged looks of mingled amusement and distress.

“Well, good butlers are hard to find . . . ,” commented Richard.

“And Stiles will be with you for a great many decades to come,” concluded Geoff.

“That’s the last time we accept an out-of-work actor into the League,” groaned Richard. “I suppose it could have been worse—he could have had delusions of being Julius Caesar and gone about in a toga.”

“He would have fit right in with the members of the Council of Five Hundred,” Geoff commented wryly, referring to the legislative body set up by the revolutionaries in 1795 in an attempt to imitate classical models of government. “About half of them were convinced they were Brutus.”

Richard shook his head sadly. “They read too many classics; such men are dangerous. At any rate, I prefer Stiles’s current delusion. I take it, as matters stand, that he hasn’t lost all track of why he’s really here?”

“If anything, he’s entered into it with even more gusto ever since he decided that he really is an eighty-year-old butler. He plays cards with Fouché’s butler every Wednesday—apparently they exchange remedies for their rheumatism and complain about the poor quality of employers nowadays,” Geoff added with a twinkle in his eye. “And he’s been carrying on a rather bizarre—if informative—flirtation with one of the upstairs maids at the Tuilleries.”

“Bizarre?” Richard sniffed hopefully as he entered the dining room, but comestibles had not preceded them.

Geoff pulled out a chair towards the head of the table and sent the pile of papers he had been holding scooting across the polished wood towards Richard. “He attained her good graces by complimenting her special formula for silver polish. They then proceeded to the intimacies of cleaning crystal.”

“Good God.” Richard began rifling through the stack of correspondence that had accumulated in his absence. “To each his own, I suppose.”

The pile Geoff had brought him contained the usual accumulations—reports from his estate manager, invitations to balls, and perfumed letters from Bonaparte’s promiscuous sister Pauline. Pauline had been trying to entice Richard into her bed since he had returned from Egypt, and the amount of perfume she poured on her letters increased with each failed attempt. Richard could smell the latest all the way from the bottom of the pile.

“How was London?” Geoff asked, signaling to a footman to fetch the claret decanter. “You look like you’re in need of a restorative.”

“You don’t know the half of it.” Richard abandoned his letters and flung himself into a chair across the table from Geoff. “Mother must have dragged me to every major gathering in London. If there was an affair of over three hundred people, I was there. I attended enough musicals to render me tone deaf, if not deaf in actuality. I—”

“No more, please,” Geoff shook his head. “I refuse to believe that it could have all been that bad.”

“Oh, really?” Richard raised one brow. He shot his friend a swift, sideways glance. “Mary Alsworthy asked after you.”

“And?” Geoff’s voice was studiedly unconcerned.

“I told her you had taken up with a Frenchwoman of ill repute and were currently expecting your third illegitimate child. By the way, you’re hoping for a girl this time.”

Geoff choked on his claret. “You didn’t. I’m sure I would have heard from my mother by now if you had.”

Richard tipped his chair back with a sigh of pure regret. “No, I didn’t. But I wanted to. It would have been informative to see if she could count high enough to realize three children in less than two years was an impossibility.”

Geoff looked away, displaying a deep interest in the arrangement of silver on the sideboard behind Richard. “There were a number of interesting developments while you were away.”

Richard let the subject drop. With any luck, by the time Geoff returned to England some other poor blighter would have fallen prey to Mary Alsworthy’s overused lures.

Richard leaned across the table, green eyes glittering. “What sort of developments?”

Geoff regaled him with tales of changes in security at the Ministry of Police (“Rather a case of closing the stable door once the horses have fled, don’t you think?” remarked Richard smugly), the frustrated ambitions of Napoleon’s brother-in-law Murat (“A weak-willed man, if ever I saw one,” commented Geoff. “He may be of use to us yet.”), and strange goings-on along the coast.

Richard’s ears pricked up. “Do you think he could be shipping munitions in for the invasion of England?” There was no need to ask whom Richard meant by “he.”

“That’s still unclear. We haven’t been able to get anyone close enough to see what’s being transported. Our connection in Calais—”

“The innkeeper at the Sign of the Scratching Cat?”

“The very one. He’s noticed an unusual amount of activity over the past few months. The serving wench at the Drowned Rat in Le Havre has similar reports. She says she saw a group of men transferring a series of large packages from a Channel packet to an unmarked carriage, and taking off down the road towards Paris.”

“Could it be just the usual smuggling activity?” Richard nodded his thanks as the footman set a bowl of potato-and-leek soup down before him, trying to quell the anticipation thrilling through him at Geoff’s news. He felt like a hound eager to bounce off after a fox. Of course, he had better make jolly sure first that it was a fox, and not just a rabbit, or a bunch of waving leaves. Or something like that. Richard rapidly abandoned the metaphor. Ever since war had broken out between England and France, the smugglers of both countries had done a brisk trade, hauling French brandies and silks to England, and returning laden with English goods. There had been one or two occasions in the past where Richard had gone haring off into the night, convinced he was on the trail of French agents carrying valuable intelligence to England, only to wind up with a boat full of disgruntled French smugglers and ten-year-old brandy. Not that Richard minded the brandy, but still. . . .

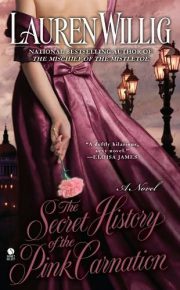

"The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" друзьям в соцсетях.