But all it takes is one, right?

And that one, Mrs. Arabella Selwick-Alderly, was currently waiting for me at—I dug the dog-eared scrap of paper out of my pocket as I scurried up the stairs in the South Kensington Tube station—43 Onslow Square.

It was raining, of course. It generally is when one has forgotten one’s umbrella.

Pausing on the doorstep of 43 Onslow Square, I ran my fingers through my rain-dampened hair and took stock of my appearance. The brown suede Jimmy Choo boots that had looked so chic in the shoe store in Harvard Square were beyond repair, matted with rain and mud. My knee-length herringbone skirt had somehow twisted itself all the way around, so that the zipper stuck out stiffly in front instead of lying flat in back. And there was a sizable brownish blotch on the hem of my thick beige sweater—the battle stain of an unfortunate collision with someone’s cup of coffee at the British Library cafeteria that afternoon.

So much for impressing Mrs. Selwick-Alderly with my sophistication and charm.

Tugging my skirt right way ’round, I rang the buzzer. A crackly voice quavered, “Hello?”

I leaned on the reply button. “It’s Eloise,” I shouted into the metal grating. I hate talking into intercoms; I’m never sure if I’m pressing the right button, or speaking into the right receiver, or about to be beamed up by aliens. “Eloise Kelly. About the Purple Gentian?”

I managed to catch the door just before it stopped buzzing.

“Up here,” called a disembodied voice.

Tipping my head back, I gazed up the stairwell. I couldn’t see anyone, but I knew just what Mrs. Selwick-Alderly would look like. She would have a wrinkled face under a frizz of snowy white hair, dress in ancient tweeds, and be bent over a cane as gnarled as her skin. Following the directive from on high, I began up the stairs, rehearsing the little speech I had prepared in my head the night before. I would say something gracious about how lovely it was of her to take the time to see me. I would smile modestly and express how much I hoped I could help in my own small way to rescue her esteemed ancestor from historical oblivion. And I would remember to speak loudly, in deference to elderly ears.

“Poor girl, you look utterly knackered.”

An elegant woman in a navy blue suit made of nubby wool, with a vivid crimson-and-gold scarf tied at her neck, smiled sympathetically at me. Her snowy hair—that part of my image at least had been correct!—was coiled about her head in an elaborate confection of braids that should have been old-fashioned, but on her looked queenly. Perhaps her straight spine and air of authority made her appear taller than she was, but she made me (five feet nine inches if one counts the three-inch heels that are essential to daily life) feel short. This was not a woman with an osteoporosis problem.

My polished speech dripped away like the drops of water trickling from the hem of my raincoat.

“Um, hello,” I stammered.

“Hideous weather today, isn’t it?” Mrs. Selwick-Alderly ushered me through a cream-colored foyer, indicating that I should drop my sodden raincoat on a chair in the hall. “How good of you to come all the way from—the British Library, was it?—to see me on such an inhospitable day.”

I followed her into a cheerful living room, my ruined boots making squelching noises that boded ill to the faded Persian rug. A chintz sofa and two chairs were drawn up around the fire that crackled comfortably away beneath a marble mantelpiece. On the coffee table, an eclectic assortment of books had been pushed aside to make room for a heavily laden tea tray.

Mrs. Selwick-Alderly glanced at the tea tray and made a little noise of annoyance. “I’ve forgotten the biscuits. I won’t be a minute. Do make yourself comfortable.”

Comfortable. I didn’t think there was much chance of that. Despite Mrs. Selwick-Alderly’s charm, I felt like an awkward fifth-grader waiting for the headmistress to return.

Hands clasped behind my back, I wandered over to the mantel. It boasted an assortment of family photos, jumbled together in no particular order. At the far right towered a large sepia portrait photo of a debutante with her hair in the short waves of the late 1930s, a single strand of pearls about her neck, gazing soulfully upwards. The other photos were more modern and less formal, a crowd of family photos, taken in black tie, in jeans, indoors and out, people making faces at the camera or each other; they were clearly a large clan, and a close-knit one.

One picture in particular drew my attention. It sat towards the middle of the mantel, half-hidden behind a picture of two little girls decked out as flower girls. Unlike the others, it only featured a single subject—unless you counted his horse. One arm casually rested on his horse’s flank. His dark blond hair had been tousled by the wind and a hard ride. There was something about the quirk of the lips and the clean beauty of the cheekbones that reminded me of Mrs. Selwick-Alderly. But where her good looks were a thing of elegance, like a finely carved piece of ivory, this man was as vibrantly alive as the sun on his hair or the horse beneath his arm. He smiled out of the photo with such complicit good humor—as if he and the viewer shared some sort of delightful joke—that it was impossible not to smile back.

Which was exactly what I was doing when my hostess returned with a plate filled with chocolate-covered biscuits.

I started guiltily, as though I had been caught out in some embarrassing intimacy.

Mrs. Selwick-Alderly placed the biscuits next to the tea tray. “I see you’ve found the photos. There is something irresistible about other people’s pictures, isn’t there?”

I joined her on the couch, setting my damp herringbone derriere gingerly on the very edge of a flowered cushion. “It’s so much easier to make up stories about people you don’t know,” I temporized. “Especially older pictures. You wonder what their lives were like, what happened to them. . . .”

“That’s part of the fascination of history, isn’t it?” she said, applying herself to the teapot. Over the rituals of the tea table, the choice of milk or sugar, the passing of biscuits and cutting of cake, we slipped into an easy discussion of English history, and the awkward moment passed.

At Mrs. Selwick-Alderly’s gentle prompting, I found myself rambling on about how I’d become interested in history (too many historical novels at an impressionable age), the politics of the Harvard history department (too complicated to even begin to go into), and why I’d decided to come to England. When the conversation began to verge onto what had gone wrong with Grant (everything), I hastily changed the subject, asking Mrs. Selwick-Alderly if she had heard any stories about the nineteenth-century spies as a small child.

“Oh, dear, yes!” Mrs. Selwick-Alderly smiled nostalgically into her teacup. “I spent a large part of my youth playing spy with my cousins. We would take it in turns to be the Purple Gentian and the Pink Carnation. My cousin Charles always insisted on playing Delaroche, the evil French operative. The French accent that boy affected! It put Maurice Chevalier to shame. After all these years, it still makes me laugh just to think of it. He would paint on an extravagant mustache—in those days, all the best villains had mustaches—and put on a cloak made out of one of Mother’s old wraps, and storm up and down the lawn, shaking his fist and swearing vengeance against the Pink Carnation.”

“Who was your favorite character?” I asked, charmed by the image.

“Why, the Pink Carnation, of course.”

We smiled over the rims of our teacups in complete complicity.

“But you have an added interest in the Pink Carnation,” Mrs. Selwick-Alderly said meaningfully. “Your dissertation, wasn’t it?”

“Oh! Yes! My dissertation!” I outlined the work I had done so far: the chapters on the Scarlet Pimpernel’s missions, the Purple Gentian’s disguises, the little I had been able to discover about the way they ran their leagues.

“But I haven’t been able to find anything at all about the Pink Carnation,” I finished. “I’ve read the old newspaper accounts, of course, so I know about the Pink Carnation’s more spectacular missions, but that’s it.”

“What had you hoped to find?”

I stared sheepishly down into my tea. “Oh, every historian’s dream. An overlooked manuscript entitled, How I Became the Pink Carnation and Why. Or I’d settle for a hint of his identity in a letter or a War Office report. Just something to give me some idea of where to look next.”

“I think I may be able to help you.” A slight smile lurked about Mrs. Selwick-Alderly’s lips.

“Really?” I perked up—literally. I sat so bolt upright that my teacup nearly toppled off my lap. “Are there family stories?”

Mrs. Selwick-Alderly’s faded blue eyes twinkled. She leaned forward conspiratorially. “Better.”

Possibilities were flying through my mind. An old letter, perhaps, or a deathbed message passed along from Selwick to Selwick, with Mrs. Selwick-Alderly the current keeper of the trust. But, then, if there were a Selwick Family Secret, why would she tell me? I abandoned imagination for the hope of reality. “What is it?” I asked breathlessly.

Mrs. Selwick-Alderly rose from the sofa with effortless grace. Setting her teacup down on the coffee table, she beckoned me to follow. “Come see.”

I divested myself of my teacup with a clatter, and eagerly followed her towards the twin windows that looked onto the square. Between the windows hung two small portrait miniatures, and for a disappointed moment, I thought she meant merely to lead me to the pictures—there didn’t seem to be anything else that might warrant attention. A small octagonal table to the right of the windows bore a pink-shaded lamp and a china candy dish, but little else. To the left, a row of bookcases lined the back of the room, but Mrs. Selwick-Alderly didn’t so much as glance in that direction.

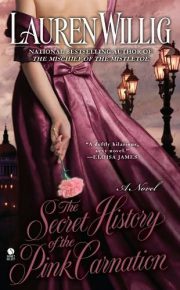

"The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" друзьям в соцсетях.