Across the room, Lord Richard was sitting in a stiff wooden chair too small for his large frame, an ankle propped against the opposite knee, utterly engrossed in what looked to be some sort of journal. Amy stared shamelessly across the room, but she couldn’t make out the title. Whatever it was, it couldn’t possibly be worse than Uncle Bertrand’s husbandry manuals. Unless . . . she had heard of one journal devoted entirely to the planting of small root vegetables. But Lord Richard really didn’t look the sort to have a turnip obsession and Amy could feel the pins and needles of nervous energy darting from her hands all the way down to her feet, pushing her forward.

Her yellow skirts made a bright splotch of color in the rapidly darkening cabin as she crossed the room.

“What are you reading?”

Richard flipped the fat pamphlet over to the other side of the table for her. Antiquarian literature usually worked as well for discouraging inquisitive young ladies as it did French spies.

Amy strained to see in the dim light. “Proceedings of the Royal Egyptological Society? I didn’t know we had one.”

“We do,” said Richard dryly.

Amy cast him an exasperated look. “Well, that much is clear.” She flipped through the pages, tilting the periodical to try to catch the light. “Has there been any progress on the Rosetta Stone?”

“You’ve heard of the Rosetta Stone?” Richard knew he sounded rude; he just couldn’t help himself. The last young lady to whom he had delivered his Rosetta Stone soliloquy had asked him if the Rosetta Stone was a new kind of gemstone, and if so, what color was it, and did he think it would look better with her blue silk than sapphires.

Amy made a face at him. “We do get the papers, even in the wilds of Shropshire, you know.”

“Are you interested in antiquities?”

For the life of him, he couldn’t figure out why he was going to the bother of carrying on a conversation with the chit. First off, he had better things to do, such as plot the Purple Gentian’s next escapade. Daring plans didn’t just invent themselves; they took time, and thought, and imagination. Secondly, voluntarily entering into conversation with young ladies of good family was inevitably a perilous venture. It gave them ideas. It gave them terrifying ideas that involved heirloom veils, ten-foot-long trains, and bouquets of orange flowers.

Yet here he was encouraging the girl to talk. Absurd.

“I don’t really know much about antiquities,” said Amy frankly. “But I love the old stories! Penelope fooling all of her suitors, Aeneas fighting his way down to the underworld . . .”

It was too dark to read, reasoned Richard. And the girl didn’t seem to be flirting with him, so carrying on a conversation with her was a harmless and sensible means of passing the time. Nothing at all absurd about that.

“I haven’t read any Ancient Egyptian literature, though. Is there any? All I know about Ancient Egypt is what I’ve read in Herodotus,” Amy went on. “And, really, I get the sense that about half of what he wrote about the Egyptians is pure sensationalism. All of that nonsense about sucking peoples’ brains out through their noses and putting them in jars. He’s worse than the Shropshire Intelligencer!”

Richard managed to stop himself from asking whether she had really read Herodotus in the original Greek. Coming on the heels of his Rosetta Stone comment, it might seem a bit insulting. “Actually, we think Herodotus may have been telling the truth on that one. In the burial chambers of tombs, we found canopic jars with the remains of human organs.” If the girl wasn’t genuinely interested, she was putting on a far better act than any Richard had ever seen.

“We? Were you actually there, my lord?”

“Yes, several years ago.”

Questions tumbled out of Amy’s mouth so quickly that Richard scarcely had time to answer one before another rolled his way. She leaned forward across the table in a way that would have had Miss Gwen barking, “Posture!” had she been awake to see it. She listened avidly as Richard described the ancient Egyptian pantheon, interrupting him occasionally to compare them to the gods of the ancient Greeks.

“After all,” she argued, “there must have been some sort of communication between the Greeks and the Egyptians. Oh, not just Herodotus! Look at Antigone—that’s set in Thebes. And so are the myths of Jason, aren’t they? Unless, do you think the Greek authors used Egypt the way Shakespeare used Italy? As a sort of miraculous once upon a time where anything could happen?”

Outside, the storm still splattered across the windows and rocked the little boat away from its destination, but neither Amy nor Richard noticed. “I cannot tell you,” Amy confessed frankly, “how good it is to finally have a genuinely interesting conversation with someone! Nobody at home talks about anything but sheep or embroidery. No, really, I’m not exaggerating. And whenever I come across someone who has actually done something interesting, they change the subject and talk about the weather!”

Amy’s face was so disgruntled that Richard had to laugh. “Surely you must allow the weather some consequence?” he teased. “Look at the impact it has had upon us.”

“Yes, but if you start talking about it, I shall have to remember something I’ve forgotten on the other side of the room or develop a passionate desire to take a nap.”

“Do you think it will be fair tomorrow?”

“Oh, so that’s your ploy, sir! You really want to read your journal in peace, so you’ve decided to bore me away! That’s terribly devious of you. But, if I’m not wanted . . .” Amy swished her yellow skirts off her chair.

The plan she described did rather resemble his intentions of an hour before, but, without even taking the time to think about it, Richard found himself grinning and saying, “Stay. I’ll give you my word not to talk about the weather if you swear you won’t mention gowns, jewels, or the latest gossip columns.”

“Is that all the young ladies of your acquaintance talk about?”

“With a few notable exceptions, yes.”

Amy wondered who those notable exceptions might be. A betrothed, perhaps? “You should count yourself lucky, my lord. At least it’s not sheep.”

“No, they just behave like them.”

Their shared laughter rolled softly through the dim room.

Richard leaned back and regarded Amy intently. Amy’s laughter caught in her throat. Somehow, his gaze cut through the gloom, as if all the light in the dim cabin were concentrated in his eyes. Suddenly dizzy, Amy lowered her hands to the sides of her chair and held on tightly. It must be that the boat is swaying more now because of the storm, she thought vaguely. That really must be it.

Richard contemplated Amy with puzzled pleasure. He did know other intelligent women—Henrietta, for one, and a few others of his sister’s circle, bright, intelligent women who were too pretty to be dismissed as bluestockings. He had even, of his own free will, dropped by the drawing room to join them in their conversations on one or two occasions. But he couldn’t imagine bantering so easily with any of Hen’s entourage.

Perhaps it was the intimacy of darkness, or of the small quarters, but absurdly, he felt quite as comfortable chatting with Amy Balcourt as he ever had with Miles or Geoff. Only Miles didn’t have immense blue eyes fringed with dark lashes. And Geoff certainly didn’t possess a slender white neck with kissable indentations over the collarbones. . . .

At any rate, Richard concluded, the Fates had known what they were doing when they set Amy Balcourt upon his boat.

“I am truly delighted to have met you, Miss Balcourt. And I promise not to talk about the weather or sheep unless it is absolutely imperative.”

“In that case . . .” Amy clasped her hands under her chin and launched back into her eager inquisition.

Only once she had satisfied her curiosity on such important subjects as tombs, mummies, and curses did Amy ask, “But wasn’t Egypt swarming with French soldiers? How did you manage to slip in?”

“I was with the French.”

For a moment, the words just hung there. Amy frowned, trying to make sense of what he had just said. “Did you—were you a prisoner of war?” she asked hesitantly.

“No. I went at Bonaparte’s invitation, as one of his scholars.”

Amy’s spine snapped upright. Head up, shoulders back, as she stared at Richard her posture locked into a steely rigidity to please even Miss Gwen. “You were in Bonaparte’s pay?”

“Actually”—Richard lounged back in his chair—“he didn’t pay me. I went at my own expense.”

“You weren’t coerced? You went of your own free will?”

“You sound horrified, Miss Balcourt. You must admit, it is the chance of a lifetime for a scholar.”

Amy’s mouth opened but no sound came out.

Richard was right; she was horrified.

For an Englishman to accompany his country’s enemy . . . to disregard all duty and honor in the pursuit of scholarship . . . Couldn’t he have waited for the English to take control of Egypt before pursuing his pyramids? And how could any man, any thinking man, any intelligent man with a modicum of feeling, have anything to do with a nation which had so cruelly and senselessly slaughtered so many of its own people on the guillotine! And to disregard all that for the sake of a few tombs! It was a slight to his country and a slight to mankind.

But, if she was being quite, quite honest, what stung most wasn’t the slight to mankind, but the sense of betrayal his words caused. It was utterly ridiculous. She had known the man all of two hours. One couldn’t really claim betrayal after two hours’ acquaintance. Even so, in those two hours, it wasn’t as though he had lied and claimed to have fought for the English and then let slip by accident that he had been with the French.

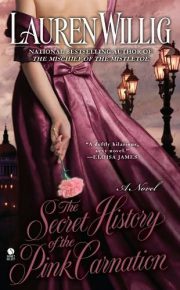

"The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" друзьям в соцсетях.