‘You will not mention Anna to me again, please,’ he said. ‘Not ever.’

By the time Rupert came to find her, Muriel was in a very nasty temper. Louise, sent for to replace Anna, had refused to wait on her and Muriel had been compelled, on a morning on which she particularly wished to dazzle, to dress herself.

‘She’ll have to be sent away, Rupert,’ she said now, angrily recounting her tale of woe.

‘There is not the slightest question of Louise being sent away,’ said Rupert levelly. He had just spent half an hour cross-examining his butler. Proom’s attempts at honourable evasion had withered before the tactics that Rupert had perfected in four years of dealing with his men. The earl was now fully informed of the situation below stairs and his anger, though perfectly contained, far outstripped Muriel’s own. ‘Louise was upset because of your treatment of Win, which, I don’t scruple to tell you, Muriel, was monstrous! As far as I can see, you virtually had the girl kidnapped on her day off.’

‘How dare you, Rupert. How dare you speak to me like that!’

‘I won’t humiliate you by countermanding the orders you have already given,’ continued Rupert as though she had not spoken, ‘but there must be no further interference with Proom’s arrangements. As for Mrs Proom, Mersham is her home and will be until the day she dies.’

‘Mersham!’ hissed Muriel. ‘Don’t talk to me about Mersham. Your precious Mersham would be under the hammer now if it wasn’t for me.’

‘Yes,’ said Rupert quietly. ‘And better it should be than that it should be destroyed by the kind of ideas perpetrated by your friend Dr Lightbody. If George were alive he’d think that too.’

‘Oh? What’s wrong with Dr Lightbody’s ideas? I happen to be about to invite him to come and work down here.’

Rupert looked at her in amazement. ‘You can’t imagine I would allow that?’ he said.

‘Allow?’ shouted Muriel, her chest heaving with operatic rage. ‘Allow! Who do you think you are?’

Rupert’s next words were spoken very softly.

‘The owner of Mersham, Muriel,’ he said.

And in the stunned silence which followed he went on more gently: ‘Surely you didn’t imagine that your wealth would allow you to bully me? As for Dr Lightbody, you are, of course, perfectly free to choose your own friends, but that I should allow a man whose ideas are wholly repugnant to me to set up shop at Mersham is quite ridiculous.’ His face creased into a smile. ‘On the other hand your relations are quite another matter.’

‘My… relations,’ faltered Muriel.

Rupert nodded. ‘Your grandmother, for example, would be perfectly welcome to make her home with us,’ he went on silkily, ‘or your Uncle Nat. I’ve always wanted to meet a rat-catcher — especially one with such original ideas about what to do with the skins.’

‘You… wouldn’t,’ said Muriel, who had turned quite white.

‘Not if you don’t wish it. But remember what I have said.’ Suddenly he reached out, took her hand: ‘Look, Muriel, you don’t love me, do you? You’re beautiful and capable and rich; you could marry anyone. It’s not too late to free yourself. Think hard, my dear — there are a lot of years ahead of us. Could you really be happy with a man who dislikes everything you hold most dear?’

Panic overwhelmed Muriel. Two days to go: literally the day after tomorrow she would be a countess! Was it possible that this glittering prize could still be snatched from her? On this very morning she had meant to tell Rupert at what times he might physically approach her. That he might find it in himself not to approach her at all had never even crossed her mind. And, squeezing her eyelids together, she managed a perfectly authentic tear.

‘Please don’t talk like that, dearest,’ she said, and for the first time he saw her genuinely afraid. ‘I’m extremely… devoted to you.’ And as he remained silent, ‘You wouldn’t… jilt me?’

Rupert shook his head.

‘No, Muriel,’ he said, trying to keep the weariness out of his voice: ‘I wouldn’t do that.’

Crossing the hall on his way out with his dog, the earl came upon a cluster of servants grouped round the library door, which had been left slightly ajar. Peggy with a feather duster, James with his stepladder… Sid.

Moving closer, he heard a voice issuing forth: high-pitched, well-modulated, self-assured…

‘… Can anyone seriously doubt, ladies and gentlemen, that the elimination of all that is sick and maimed and displeasing in our society can — and indeed must — be the aim of every thinking…’

The servants, seeing his lordship, scuttled for cover. Rupert pushed open the door. On the dais at the far end of the empty library, one hand resting on the bust of Hercules which had given Anna so much trouble, stood Dr Lightbody, testing the acoustics of his new home.

Rupert entered, Baskerville at his heels. The door shut behind him. The servants crept slowly forward again. Till the door flew open and a dishevelled, blond-haired man shot out into the hallway and collapsed in a heap on to the mosaic tiles…

Very late that night, Proom, on his last rounds, found a light still burning in the gold salon and went to investigate.

Lying sprawled on a sofa, his head thrown back against the cushions, one arm flung out — was his lordship. His breathing was stertorous; the decanter of whisky on the low table beside him was empty.

For a long moment, Proom stood looking down at his master. Something about the pose of the body, both taut and abandoned and the weariness of the slightly parted lips, half-recalled an entry he had seen in one of his encyclopaedias… Something about ‘Early Christian Martyrs’, he thought. Then suddenly it came to him: Botticelli’s altarpiece of St Barnabas in the Uffizi.

He leant forward to shake his lordship by the shoulder. Whereupon the earl opened an unfocused eye, pronounced, with perfect clarity, a single word — and at once passed out again.

‘Tut,’ said the butler, expressing in the only way he knew, his deep compassion.

Then he went downstairs to order James to come and help him carry his lordship to his bed.

On the following day, the last before the wedding, Mr Proom received a telephone call. It was from the station master at Maidens Over and informed him that a family by the name of Herring had been apprehended while trying to cheat the Great Western Railway of two fares.

‘Where are they now?’ asked Proom when he had digested this piece of information.

‘They are locked in my office, Mr Proom, pending further investigations. What would you wish me to do with them?’

‘If you would be so kind as to keep them there, Mr Fernby,’ said Mr Proom. ‘Just keep them there. On no account let them out till I arrive.’

‘It will be a pleasure, Mr Proom,’ said the station master.

But when he had replaced the receiver, Proom did not go to find the earl or the dowager. Instead he stood for a long time lost in thought. Mr Proom remembered Melvyn Herring. He remembered him very well…

‘It is impossible,’ said Mr Proom to himself after a while. And then: ‘It is absurd. I must be losing my reason even to think of such a thing.’

He continued to stand by the telephone, the light reflecting off his high, domed forehead. ‘Quite absurd,’ he repeated, ‘and in the worst possible taste. Yet could anything be worse than things as they are now?’

They could not. And presently Proom went first to find James to tell him that he would have to deputize for a few hours, and then to Mr Potter to ask if he could spare one of the cars.

Leo Rabinovitch was working in his study. He had retired from the rag trade, but his business sense was inborn and since he and Hannah had come to the country their wealth, due to his astute investments, had trebled. Now it seemed as though his fortune would go, not as he had hoped, to further the interests of the Cohens or the Fleishmanns or the Kussevitskys, all of whom had sons whose mothers had watched Susie reach marriageable age with unconcealed interest, but to the Byrnes, whose record in matters like the burning of the synagogues in medieval York, for example, was far from impressive. Still, there it was. Tom was a nice lad and Susie’s very spectacle frames, since the ball, seemed to have turned to gold.

It was at this point that the parlourmaid, round-eyed with wonder, announced Cyril Proom. Proom had come to the front door, a gesture which had brought beads of perspiration out on his forehead, and the maid had nearly fainted. Not because she had expected him to come by the back door either. She had simply expected him to be for ever at Mersham; immaculate, planted, there.

Rabinovitch looked up — and was at once attacked by a deep, an almost ungovernable lust.

Hannah was a good housekeeper. The Towers ran well, the food was excellent, the rooms clean and cared for. But Hannah, sensibly knowing her limitations, stuck to women servants, and these she treated in the traditions that prevailed in the village homesteads of her youth. In the servants’ quarters of The Towers nothing was secret, nothing, felt Leo Rabinovitch, was spared. The Rabinovitches’ maids got the shingles and the piles and were nursed by Hannah. They were crossed in love and their sobs floated up to the study where Rabinovitch was trying to read his company reports. They dreamt about nesting crows and royal babies and fire engines and told him so while serving breakfast. They walked in their sleep, their aunts fell off bicycles, poltergeists infested their cousins’ cottages — and every disaster, minutely chronicled, reverberated through the rooms and corridors of his house.

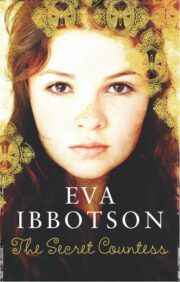

"The Secret Countess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Countess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Countess" друзьям в соцсетях.