So they danced and neither of them spoke. As the music began and his arms closed round her, he had felt her shiver. Then the melody caught her and she moved with him, so light, so completely one with him that he could guide her with a finger. Yet as he held her he had no thought of thistledown or snowflake. Here, beneath his hands, was tempered steel, was flame…

He checked, reversed, and she followed him perfectly. It seemed to him that she could fold her very bones to lie against his own. And tightening his arms, drinking in the smell of green soap, of cleanliness personified, which emanated from this changeling countess, he allowed his mind, soaring with the music, to encompass their imagined life together.

He had not wanted Mersham — had returned to it reluctantly as to a burden he must face. In the few weeks she had been there, Anna had changed all this. Her feeling for his home was unerring, as inborn as perfect pitch in music. Bending to arrange a bowl of roses, standing rapt, with her feather duster, before the Titian in the morning room, bringing in the mare at daybreak, each time she seemed to be making him a gift of his inheritance. Like those dark Madonnas on the icons whose patient hands curve up towards their infants’ heads, Anna’s every gesture said: ‘Behold!’

Anna, in his arms, was without thoughts, without dreams. Rupert had imagined her folding her bones to shape them against his. She had done more. She had folded her very soul, given it into his keeping — and danced.

‘Oh, God!’ said the dowager softly. And then to Minna, standing beside her. ‘Did you know?’

‘That Peter was her brother? I guessed almost as soon as he came. Or did you mean…?’

She did not finish. There had been no scandal yet — only a drama of the kind that any hostess must delight in. Her Harry had led Muriel first on to the floor; Tom, good soul that he was, was dancing with Lavinia; other couples had quickly joined in and were swaying and swirling beneath the glittering chandeliers. Yet it seemed to Minna and the dowager that there was no one in the ballroom except those two.

‘If only they would talk,’ said the dowager.

And indeed the silence in which those two danced was as terrible as an army with banners. Only Muriel, armoured by her outrage at Anna’s presumption as she gyrated heavily in the arms of her host, entirely failed to see what had happened.

‘What an extraordinary business,’ said the Lady Lavinia, lurching in her skirted codfish costume against the long-suffering Tom. ‘Is she really a countess?’

‘Yes.’

Tom had seen Susie come in. She was dressed as a gypsy and accompanied by her mother in the costume of a Noble Spanish Lady — and by that stout bullfighter, Leo Rabinovitch. If only he could get to Susie it would be easier to bear what he had seen in Rupert’s face.

‘Muriel doesn’t like it, does she?’ continued Lavinia with satisfaction. ‘She looks as though she’s swallowed a porcupine.’

Tom glanced at Rupert’s fiancée. Muriel certainly looked angry, but he could see no sign on her face of distress or pain.

But now the music was gathering itself up, manoeuv-ring for the climax. Mr Bartorolli had done all he could. With his fine social antennae he had understood exactly what was happening. The ball might be for the stiff, white-wigged lady in silver, but it was about the young girl with her ardour and her Byzantine eyes who seemed to be one flesh with the young Earl of Westerholme. So he had played the first repeat, the second, demanded — to the surprise of his orchestra — a reprise. But now there was nothing more to be done. For the last time, the melody soared towards its fulfilment, the dancers turned faster, faster… and with a last, dazzling crescendo, the music ceased.

It was over.

They drew apart and for a moment Anna stood looking up at him, dazed by the silence.

Then, for the last time, she curtsied.

If it hadn’t been for that curtsy, Rupert would have left her then and there. He expected no more miracles. But what she made of that gesture, combining her former respect and humility with the elegance, the lightness of the ballroom — yet all of it, somehow, heartbreakingly on a dying fall — was more than he could bear.

‘Come outside for a moment. You must be hot.’

She shook her head. ‘No, Rupert.’

He did not hear the denial, only that she had used his Christian name — and followed by every pair of eyes in the room he led her out, still protesting, through the French windows and on to the terrace. Nor did he stop there but, as familiar with Heslop as with Mersham, led her down a flight of shallow stone steps to an arbour with a lily pond and a stone bench, protected by a high, yew hedge.

‘Anna,’ he said, guiding her to the seat, ‘I shall do what is right. I shall not jilt Muriel. The mistake is my mistake and I will live by it. But if you have any mercy tell me just once that you feel as I do? That if things had been different…’ He drew breath, tried again. ‘That you love me, Anna. Is it possible for you to tell me that?’

She was silent, and suddenly he was more frightened than he had ever been. Then she turned towards him and gave him both her hands to hold and said very quietly: ‘I have no right to tell you, you belong to someone else. But I will tell you. Only I will tell you in my own language so that you will not understand. Or so that you will understand completely. Listen, then, mylienki, and listen well,’ said Anna — and began to speak.

It was already dusk. The ancient yews which sheltered them stood black against a sky of amethyst and fading rose; close by the fountains splashed and from the ballroom came the sound of a mournful, syncopated melody filched from the negro slaves.

And Anna spoke. In the wonderful, damnable language that separated yet joined them, with its caressing rhythm, its wildness and searing tenderness. He was never to know what she said, but it seemed to him that the great love speeches of the world — Dido’s lament at Carthage, Juliet’s awakening passion on the balcony, Heloise’s paean to Abelard — must pale before the ardour, the strange, solemn integrity of Anna’s words. And allowing himself only to fold and unfold her pliant fingers as she spoke, he saw before him her whole life: the small child, shining like a candle in the rich darkness of her father’s palace, the awakening girl, wide-eyed at the horrors of war… He saw her as a bride, faltering at the church door, dazzled by joy, and as a mother, cupping her slender, votive hands round the head of her newborn child… He saw her greying and rueful at the passing of youth and steadfast in old age, her eyes, her fine bones triumphant over the complaining flesh. And he understood that she was offering him this, her life, for all eternity and understood, too, where she belonged because her sisters are everywhere in Russian literature: Natasha, who left her ballroom and shining youth to nurse her mortally wounded prince… Sonia, the street girl who followed Raskalnikov into exile in Siberia and gave that poor, tormented devil the only peace he ever knew.

‘Have you understood?’ she asked when she had finished.

‘I have understood,’ said Rupert when he could trust himself to speak.

Then he bent to kiss her once very lightly on the lips and went back to the house to find his bride.

Muriel, however, was nowhere to be found. She was not in the ballroom, nor in the great hall and Tom, the most recent of her partners, said that she had excused herself to go upstairs.

The sudden elevation of her lady’s maid to the status of a guest had infuriated Muriel, but she had suffered no personal anxieties. The thought that anyone could be preferred to herself was not one that had ever crossed her mind. And when she had danced with the admiring Dr Lightbody and the dutiful Tom, it seemed to her, Rupert being temporarily absent, a perfect moment to carry out her plan.

First, the cloakroom, where she had left a large parcel which she now retrieved, opening the cellophane-covered box and looking at its contents with a satisfied smile. Yes, the doll was a triumph! White porcelain eyelids with thick, blonde lashes closed with a click over round, china-blue eyes; golden curls clustered under a muslin bonnet and when up-ended she clearly and genteely pronounced the word: ‘Mama’. No, Muriel did not grudge the expense though it had been considerable. Ollie would love a doll like that and, after all, Dr Lightbody had been right that day at Fortman’s. Diplomacy was needed in a case like this — it wasn’t as though she was dealing with servants. Whereas if she carefully explained to Ollie how exhausting the ceremony would be, how harmful it would be for her to stand for a long time on her bad leg, how much better to rest quietly at home with this lovely doll, Ollie would surely cooperate.

Ollie’s marigold head had been absent for a while now from the minstrel’s gallery. The child would certainly be in bed by this time. Muriel had found out where she slept. The problem now was seeing that she got to her alone.

Tom had been assiduous so far in the performance of his duties. He detested dressing up but he was wearing the navy sweater and bell-bottoms of a sailor in His Majesty’s Navy. He was indifferent to dancing, but he had waltzed with the detestable Lady Lavinia and snatched Muriel Hardwicke from Dr Lightbody’s arms when the music ceased, so as to give Rupert a few last minutes of happiness.

Now, however, he felt entitled to some solace and by this Tom meant — and had meant for the past two years — the company of the plump and bespectacled Susie Rabinovitch.

He found her, as he might have expected, with her mother, making easier by her uncomplicated presence the first emotional meeting between Hannah and the dowager since the day at Maidens Over.

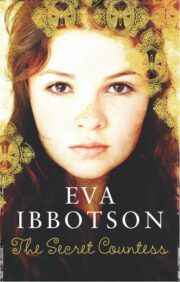

"The Secret Countess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Countess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Countess" друзьям в соцсетях.