‘I’ll take her along to get started,’ said Hawkins now. ‘She’s too late for tea, the girls are just coming out.’

Anna, who due to Muriel’s bullying had had no lunch, repressed a sigh, curtsied to the housekeeper and followed Mr Hawkins down a short flight of steps, along a winding corridor and through an enfilade of sculleries and store rooms to the pantries. Minna had done everything she could to provide her servants with comfort: the floors were carpeted, there were electric lights, new boilers, glass-fronted cupboards — but the tone of an establishment is set by those who run it and Anna was not surprised, passing the kitchens, to hear a scream and see the door burst open to eject a hysterically weeping kitchen maid, who gave a gasp of terror at the sight of Hawkins, threw her apron over her head and scuttled blindly away.

Mr Hawkins stopped at the door of a large pantry where three girls, under a barrage of admonitions from the first footman, were laying out trays of glasses and cutlery.

‘Here’s the Russian girl, Charles,’ said Mr Hawkins, pushing Anna into the room. ‘She’s to go upstairs at eight, but there’s plenty of time for her to make herself useful before then.’

‘There is indeed,’ said the first footman with a sour smile. He turned to Anna. ‘You can start by rinsing all those knives through hot water and polishing them. Hot water, mind, and no fuss about it hurting your hands. The sink’s over there.’

Watched by the hostile eyes of the other girls, Anna went to work.

Upstairs, Heslop was en grande tenue. The great hall blazed with lights, tubs of poinsettias and camellias glowed like captive fireworks against the rich darkness of the tapestries. In the ballroom with its triple row of chandeliers, Minna, remembering that she was welcoming a bride, had kept the flowers to white: delphiniums, madonna lilies, roses and the quivering, dancing Mexican poppies that she loved so much. Garlands of white ribbons and acanthus leaves wreathed the long mirrors, and the end windows, on this lovely summer evening, stood open to the terrace with its fountains of rampaging gods, its lily ponds…

Minna had dressed early and now walked quietly from room to room checking details; the French chalk spread evenly over the dance floor; the clustered grapes arranged in a suitably dying fall over the chased silver bowls; velvet cushions placed on the chairs put out for Mr Bartorolli’s orchestra… She wore the dress her Puritan great-grandmother had worn for her Quaker wedding: dove grey silk with a wide, white collar. Like her husband, Minna did not care for fancy dress, but she was glad now of the dignity lent by the old-fashioned dress. If she was to welcome Muriel Hardwicke as she should be welcomed, she had need of every aid to mannerliness and poise. Now, pausing for a moment at the door of the state dining room, where two whispering footmen were putting the finishing touches to a dazzling cold collation on the sideboard, she nodded, well pleased. There had been disasters and clashes below stairs, the chef had given notice no less than seven times, but now, like a prima donna who forgets her rehearsal tantrums, Heslop was ready to go on stage.

Minna went upstairs, smiling as she passed her husband’s dressing room and heard the choleric expletives which attended the efforts of his lordship’s valet to button him into the dress uniform of an eighteenth-century hussar, and hurrying quickly past the suite she had allocated to the Nettlefords, she entered Ollie’s room.

‘Look, Mummy, look at Hugh and Peter, aren’t they smart!’ Ollie’s eyes shone with pride as she pointed to her brother and the schoolfriend he had brought down from Craigston — and indeed the two boys sitting side by side on the window-sill in their cadet uniforms were quite spectacularly scrubbed and brushed. ‘Peter says he’ll stay up in the minstrel’s gallery with me at the beginning to watch the guests arrive and afterwards he’s going to creep up and bring me things to eat. I can stay up long enough for that, can’t I?’

Minna nodded and smiled affectionately at Hugh’s new friend who, in the space of two days, had become the object of Ollie’s hero worship. Not only the boy’s nationality but his temperament had been a surprise and delight to Minna. Peter was a first class boxer, Hugh said, and had won the Junior Fencing Cup within a few weeks of arriving at school. And yesterday, when the boys had gone out riding, Tom, with whom horses were almost a religion, had offered Peter his own hunter to ride whenever he wished. Yet he was interested in matters which most English boys would have considered effete or embarrassing: textures and fabrics, even flowers. It was to Peter that Ollie, slowly recovering from the wound that Muriel had inflicted, showed her bridesmaid’s dress and his unfeigned interest, his support during the wedding rehearsal on the previous day, had enabled Ollie to hold her head high and to aquit herself with distinction. If Ollie was once again looking forward to Muriel’s wedding, it was largely due to the Russian boy.

Back in her room, Minna sat for a few moments, absently dabbing scent behind her ears. If only things had been different she might have hoped, in years to come, of a marriage between Ollie and just such a boy as Hugh’s new friend. Whereas the way things were…

Then there was a knock at the door and Peter’s blond head appeared round it. ‘There has been a disaster with the head of John the Baptist,’ he said, grinning. ‘Lady Hermione has sat on it and wishes to know if—’ He broke off, came into the room. ‘You are sad?’

‘No…’ Minna shook her head, then remembered that the ‘nothing-is-the-matter’ technique had never gone down well with the Russians of her acquaintance. ‘But it won’t be easy for Ollie later… at dances… at balls…’

The boy closed the door and came to stand beside her chair. ‘We have a proverb in Russia,’ he said. ‘It goes: “The fox knows many things but the hedgehog only knows one thing”. Ollie, I think, is a hedgehog — like her Alexander.’

‘And what is the one thing that she knows?’

‘How to make people love her,’ said Peter quietly.

Minna looked up, tears in her eyes. She had never known a boy of thirteen who could speak like that — who could use, so unaffectedly, a word which even her own boys shied away from — and the suspicion she had entertained from the moment she met him hardened into near certainty. But she only brushed his cheek lightly with her fingers and said: ‘You know, Peter, I think I shall change my plans and get you to take Honoria Nettleford into supper!’

Anna had been in the pantry for an hour, bent over a sink of near-boiling water. After an exchange of giggles, the spiteful girls who worked with her had made a point of tipping a treble load of soda into the water every time she changed it and her hands, already chapped and raw, hurt so much that it was all she could do not to cry out. But she kept on and at last even Hawkins could not postpone her journey upstairs any longer.

The main entrance at Heslop led into a domed vestibule from which the grand staircase swept upwards and the original Elizabethan hall, raftered and galleried, opened on the right. It was in the hall that the guests would be greeted and assemble for conversation and light refreshment before ascending to the ballroom, a later addition reached by a flight of shallow stairs at the far end.

Anna, following Hawkins up the service stair, received a spate of instructions over his shoulder. ‘There’ll be two footmen at the entrance and two at the foot of the stairs and I’ll be doing the announcing. You’re to stand out of the way in the great hall beside the service table. Mr Briggs is in charge there,’ he said, referring to the tyrannical and sour-faced Charles. ‘He’ll tell you when you’re to take up a tray and offer drinks. There’s to be no putting yourself forward — and no slacking either. And remember, the ballroom’s out of bounds — you’ve no call whatever to—’

He stopped with an exclamation of annoyance, aware that Anna was no longer following closely. She had suddenly stumbled, had put out a hand to the wall of the corridor, trying to steady herself.

‘What on earth are you doing?’ he asked sharply, but he was anxious too. What if the wretched girl should faint on him? Perhaps he should have let her have some tea?

But it was no longer hunger or exhaustion that had made Anna stumble, though she was tired enough. It was a fragment, a haunting, insiduous snatch of melody carried across the well of the servants’ courtyard by a suddenly opened door. A tune known and loved from childhood which came, now, as only music can, to break down her defences and flood her with such longing, such an agony of homesickness for the world that was lost to her for ever, that she thought she would die of it.

‘What on earth did you bring that for?’ said the first violinist, putting down his bow. ‘It’s as old as the hills, that.’

‘Oh, I dunno,’ said Mr Bartorolli, alias Bert Phipps of Bermondsey. ‘I just put it in at the last minute.’ He shrugged and put the yellowing sheets of the ‘Valse des Fleurs’ back on the piano. Then he continued to hand out freshly bound copies of the latest hits: two-steps and tangos, to the musicians now arranging their places on the dais.

‘The Earl of Westerholme, The Lady Lavinia Nettleford, The Dowager Countess of Westerholme, Miss Muriel Hardwicke, Miss Cynthia Smythe, Dr Ronald Lightbody,’ announced Hawkins, and the party from Mersham moved through into the hall and towards the great fireplace, where Lord and Lady Byrne, with Tom, were waiting to greet their guests.

Minna embraced the dowager, who was becomingly and, she herself considered, aptly dressed as Mary Queen of Scots Ascending the Scaffold, and turned to welcome what appeared to be an outsize codfish or perhaps a trout.

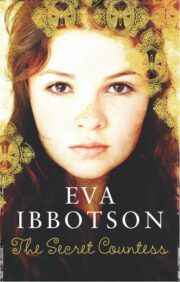

"The Secret Countess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Countess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Countess" друзьям в соцсетях.