‘Soon it will be time to begin the grouse shooting, will it not?’

A sudden, violent thump against the door of the servants’ hall interrupted her. A second and louder thump achieved its objective. The door burst open and, in concerted amazement, the staff looked up at the figure thus revealed.

‘That I should live to see the day!’ said James. ‘That great, drooling snob showing his face down ’ere!’

Torn between despair and embarrassment, between loneliness and shame, the earl’s dog stood before them, his great head raking the room. He had done it, the unspeakable thing. The degradation, the horror of it, was behind him — and now where was she? Had it all been in vain; the debasement, the agony, the choice?

But no, it was all right. He’d seen her. She was there. She would make whole what was broken, console him for his master’s absence, would understand his imperative need to be scratched now, this minute, and for a long time in that special place behind his ear. To show too much joy in a place such as this would be unseemly but, as he padded towards her, his tail was extended in a manner which would make wagging possible should all go as expected. Anna just had time to pull back her chair before he was upon her, butting and blowing, letting his head sink, at last, with a moan of relief on to her lap.

She put up a hand to scratch him, and as she bent forward the pins, jabbed ill-temperedly back on her head by the frustrated René, loosened, sending a strand of her uncut hair forward across her shoulders.

‘Oh, Baskerville,’ said Anna — and only then began to cry.

12

Inner peace now descended on Baskerville, who found his new life of abasement below stairs a beguiling and hitherto undiscovered world of the senses. It did not, however, descend on the focus of his adoration, Anna Grazinsky.

Anna had not caught so much as a glimpse of the earl since he’d walked out of René’s shop in Maidens Over, which made her suppose that he, too, was avoiding any place where they might meet. Worked off her feet, as were all the maids, Anna had in addition to act as handmaiden to the incessant bodily horticulture with which Muriel prepared for her Great Day. Packs of oatmeal and buttermilk had to be poured over Muriel’s white limbs, purées of soft fruit to be smeared on her face. Pummice-stoning Muriel’s elbows, massaging egg-white into her scalp, applying an amazing quantity of sliced cucumber to her eyelids as she floated in the bath kept Anna in a state of bemused exhaustion from dawn to dusk. For the rest, she kept silence. Only her eyes betrayed her wonderment that love, when it came at last, should be so physical, so exhausting and so sad.

The fatigue below stairs, the anxiety above, as the dowager wondered whether Uncle Sebastien, aged by five years in the last weeks, would get to the church to give away the bride, were not echoed by Muriel herself. Muriel felt fine. With five days to go she was certain that her decision to have a quiet wedding at Mersham had paid off. Not one of her father’s disreputable relatives had shown any sign of life and soon, now, Dr Lightbody would arrive to see the completion of her journey into the aristocracy.

Yet at the very moment that Muriel was anticipating his arrival with such pleasure, the doctor was sitting in an ante-room in the Samaritan Hospital in the Edgware Road, in a state of bewilderment and shock.

‘I can’t believe it,’ he said, shaking his blond and handsome head. ‘It isn’t possible. Not Doreen.’

‘We’ve expected it for some time, Dr Lightbody,’ said the matron, who had indeed tried several times to give the obstinate man an idea of his wife’s condition. ‘She was very ill when she was admitted, as you know. It was only a matter of time.’

Alone in his lodgings that night, the doctor sank wearily into his chair. He was a widower. Doreen had done the unbelievable thing and without a word to him, without, so to speak, his permission, she had died. Really, it was quite appalling, quite unbearable.

And not only that. In two days’ time he was supposed to go to Mersham, to Miss Hardwicke’s wedding and the ball which preceded it.

He would have to cancel it, of course. But how dreadfully disappointed Miss Hardwicke would be. She had been so interested when he had hinted that he might be willing to come and work at Mersham. And how agonizing it was for him to break his word.

But would he in fact have to break it? The doctor rose and walked over to the mirror. Considering the shock he had just sustained he was looking wonderfully well. Supposing he went very quietly to the wedding? In a black armband to signify bereavement, emitting a restrained sadness which could not fail to touch Miss Hardwicke’s heart. Yes, in a sense it was his duty to go. One could, after all, be a little vague about exactly when Doreen had died.

Yes, he would go to the wedding. It was, when all was said and done, a religious ceremony. But not to the ball. People might really think it was odd if he came to the ball in a black armband. And in any case a black armband would not go at all well with the white tunic, the golden circlet of laurel leaves and the lyre of Apollo. Sighing, the doctor moved over to the wardrobe and opened it. Nathaniel and Gumsbody had done him proud — the outfit was extremely becoming, simple yet regal, and they had thrown in, at half price, a bottle of liquid make-up for his arms and legs. He had tried a little on his knees last night and the effect was excellent: sportive yet glowing. But of course a black armband would kill that. It was impossible.

For a while he stood looking at the white folds of the chiton, the finely wrought sandals. Was he perhaps being rather selfish, obtruding his grief like that? Why wear a black armband at all? Why, in fact, tell anyone that Doreen had died? To go, keeping to himself this bereavement, to pretend to laugh and dance and be merry when his heart was breaking — was not that the noble thing? Was that not what Apollo himself would have counselled? To dance with Miss Hardwicke, to hold in his arms her full-breasted, white skinned loveliness, to remind her, under cover of the music, of her procreative duties, was that not a worthier task than to sit here mourning and grieving, a victim of self-pity and despair?

Of course there was the funeral. But Doreen’s parents, with whom she had never quite cut off relations though he had begged her to often enough, would be only too happy to organize all that without interference. And a thoroughly lower-class business it would be — but that was their affair. The actual interment, after all, wouldn’t be for at least a week and he’d be back by then.

Yes, it was a hard choice, a task that would take all his self-control but he would do it. He would go to the wedding and the ball — and somehow contrive to enjoy himself. In which case, as he was going to see the florist anyway about a suitable wreath, he’d better enquire about a white carnation to go with the morning clothes he’d hired. Or would a gardenia be better? That is, if gardenias were worn at country weddings before lunch…?

The Herrings, meanwhile, had perfected their plan for getting to Mersham with a minimum of financial outlay. It was a complicated plan and though Melvyn had explained it several times to Myrtle, she was having trouble with it, her physical endowment, though generous, not being of the kind that extended to the grey matter of the brain.

‘Look, it’s like this,’ Melvyn explained patiently. ‘I buy one ticket for the two of us, see?’

‘What with?’ asked Myrtle, unhooking her corsets, for they were preparing for bed.

‘Just leave that to me, will you? I buy a return ticket, see? Then you wait till there’s a good crowd pushing round the barrier an’ you go through and give up your half of the ticket all properly like, and as soon as you’re through you push the return bit of the ticket back in my hand. Then I come along and the inspector says, “Tickets, please” and I say, “I’ve already given it to you”.’

‘But you haven’t,’ said Myrtle, rubbing the weals the whalebone had left in her burgeoning flesh.

‘No, Myrtle; I know I haven’t. Because you have. So then I say, all innocent like, “But I gave it to you” an’ he says, “No, you didn’t” and I say “Yes I did an’ if you look you’ll see I have because ’ere’s the return half with the number on it and if you look you’ll find the same number on one of the tickets in your hand.” And then ’e looks and sure enough, there it is.’

‘What about the twins?’ asked Myrtle, slipping back into the black crêpe de Chine petticoat that did double duty for a nightdress. That was what she liked about black undies; there wasn’t all that bother about washing them.

‘We’ll do the same with the twins. Buy one ticket between the two of them.’

‘All right. Only you go and explain to them what they’ve got to do.’

Melvyn rose and opened the door of the adjoining room. Owing to an unfortunate spot of bother with the bailiffs, the twins were sleeping on a mattress on the floor. Dennis was lying on his back; his full-lipped mouth hung open and, as he breathed, the mucous in his nose bubbled softly like soup. Beside him lay Donald, apparently overcome by sleep in the act of eating a dripping sandwich, the dismembered remains of which lay smeared across his face.

Melvyn stood looking down at the swollen cheeks, the pendulous chins and bulging arms of his offspring and his fatherhood, never a sturdy plant, wilted and died.

‘Meat,’ he said wearily to himself. ‘That’s all they are. Just blobs of meat.’

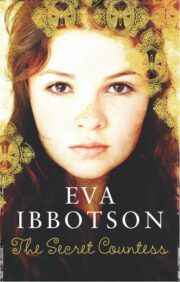

"The Secret Countess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Countess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Countess" друзьям в соцсетях.