‘No… no.’

Her father, who had come in from a day of frustration, trying to make the tsar listen to reason over some matter of policy, and gone up to say goodnight to her, plunging his hands into her hair where it lay spread on the pillow as into a cooling stream. ‘And yet it isn’t cold, your hair; it’s as warm as the rest of you. Fire water you’ve grown there, my silly Little Candle.’

More and more memories came. Sergei, pulling her out of the river by her hair when she fell out of the rowing boat at Grazbaya. The Princess Norvorad, her godmother, that formidable grande dame whom the Bolsheviks had gunned down in the cellar of her house, loosening her braids as she came with Pinny into the drawing room and saying in her exquisite, archaic French: ‘After all, ma chère, we need not despair. Something can be done with her, I think. Yes, something can certainly be done.’ And Pinny, who, every night, ignoring the grumbles of the nursery maid, had herself administered the three hundred strokes with the Mason Pearson hairbrush from the English shop in the Nevsky…

Am I mad? Anna now thought, as René, with a flourish, put down his comb. Am I completely mad to cut my hair?

One last memory rose before her: not of Russia, not of her childhood. A recent one… by the lake at Mersham… of herself standing in the water desperately shaking out her damp locks so as to cover her naked shoulders, her breasts…

And with this image came courage and determination. She lifted her head.

‘I am ready, monsieur,’ said Anna. ‘Please begin.’

Anna was not the only person from Mersham visiting Maidens Over on the Wednesday before the wedding. Rupert, who had business with his solicitor, had driven his mother over so that she could visit Mrs Bassenthwaite in hospital and purchase some trimmings for the wedding outfit which Mrs Bunford was excitedly savaging in honour of The Day. Now, her tasks completed, she sat in the comfortable, chintzy lounge of the Blue Boar Hotel taking tea with her great friend, Minna Byrne.

‘So everything’s going splendidly, Mary?’ asked Minna Byrne, wondering why the Dowager Countess of Westerholme, with her fine bones and inherent elegance, should so resemble, a scant week before her son’s wedding, the hungrier kind of alley cat.

‘Oh, yes; quite, quite splendidly,’ said the dowager brightly. She closed her eyes for a moment as though to banish the spectre of Uncle Sebastien, sitting caged and shamed in the east wing with that unspeakable nurse; of Rupert, who had returned from Cambridge only to ride off at daybreak to the furthest corner of his estate; of Cynthia Smythe, who had arrived the previous day and whose idea of making herself useful was to follow Muriel from room to room, obsequiously repeating her remarks. The servants, too, all seemed to be going mad, knocking on her door one by one and begging her to take them to the Mill House at half their wages to do work that was grossly beneath them. James asking to be a handyman, Mrs Park offering to be a cook general and to scrub! Only she couldn’t take them, how could she? There wasn’t the money or the room. And Mrs Bassenthwaite really had lost her memory; she’d remembered nothing, just now, about the arrangements made for Win. ‘Yes, everything’s fine,’ the dowager repeated — and launched into a description of the menu for the wedding breakfast, an inventory of the presents received, an account of the trousseau for the honeymoon, which was to be short and spent in Switzerland. ‘And Muriel has been marvellously efficient. She’s dealt with everything. You can imagine what a comfort I have found it.’

‘She seems to be a most capable girl,’ said Minna.

‘Oh, she is, she is! Muriel never dithers like some girls. She knows her own mind.’

‘And she’s so very beautiful,’ said Minna.

‘Yes, indeed. That creamy skin.’

‘And her eyes. So very blue.’

‘She carries herself well, too,’ said the dowager. ‘It’s so unusual these days to see a girl that doesn’t slouch.’

A silence fell. Minna, about to embark on a sentence in praise of Muriel’s good health, abandoned it, aware that she was beginning to sound distinctly agricultural. Both women were light eaters, but they paused now to order crumpets.

‘How’s Ollie?’ asked the dowager. ‘We haven’t seen her for a while.’

‘She’s fine.’ It was Minna’s turn, now, to push away her anxieties. The bridesmaid’s dress had arrived and Ollie had seemed pleased. It was going to be all right, surely? ‘She’s looking forward very much to Hugh coming home. He gets back tomorrow with this new friend who seems to be a paragon of all the virtues. Just as well, with Honoria Nettleford and her brood as house guests!’

The dowager smiled. ‘I can’t thank you enough for that. Honoria and the Herrings under one roof really wouldn’t have done!’

‘I’d have had Lavinia too, but she’ll want to be with Muriel,’ said Minna. ‘And everything’s settled for the ball. I’ve got Bartorolli to play, did I tell you? Snatched him from the Duchess of Norton with an hour to spare! Quite a coup! Oh, and you won’t forget to let me have Anna, will you. I’ve an absolute spate of foreigners coming.’

‘No, indeed.’ The dowager’s face had softened at Anna’s name. ‘Proom’s arranged for her to get over to Heslop early so that Hawkins can instruct her in her duties. It’ll mean someone else will have to dress Muriel and I’m afraid she won’t like it but—’ The dowager broke off. ‘Oh, good, there’s Hannah! I haven’t seen her for days.’

Hannah Rabinovitch had entered the lounge, loaded with parcels, and was picking her way between the tables, looking for one that was free. The dowager rose, waving one of her chiffon scarves. ‘Here, Hannah! We’re over here!’

Hannah looked up and saw her. She took a few eager steps forward — and paused, a deep flush covering her face. Then abruptly she turned, walked quickly back to the door, and vanished.

The dowager sank back into her chair, her eyes smarting with sudden tears. There are greater griefs than rejection by a valued friend, but none which wound more instantly.

‘She cut me, Minna! Hannah cut me dead! I don’t understand it — I’ve never known Hannah do anything like that before.’ She tried to pick up her cup, found that her hands weren’t steady, and put it down again. ‘Could it be that Muriel hasn’t thanked her for the wedding present? They sent an absolutely priceless dinner service. But Muriel swore she’d write and anyway Hannah isn’t like that; she’s the least stuffy person I know. And I won’t see her now till the wedding…’

Minna hesitated. Susie had come to see them the day after Muriel’s note had reached The Towers. She’d been quiet and resigned on her own behalf, but when she spoke about her mother there had been something in her voice that had sent Tom, later that night, stamping up and down the great hall like a madman, raking his red thatch of hair and spitting fire. ‘If it was anyone else in the world but Rupert I’d turn the whole thing in, even now, but I can’t do it to him. Oh, God, I could kill her; I could wring her neck in cold blood. How dare she, how dare she?’

Minna had made up her mind. ‘I don’t think Hannah is coming to the wedding, Mary,’ she said quietly.

The dowager stared at her friend, suddenly feeling old and stupid and utterly at sea. ‘What do you mean? They’re not going to be away, are they? Surely Hannah would have told me?’

Minna searched for words that carried no overtones of malice. ‘Muriel felt that… a Christian ceremony would embarrass them. That they would feel… out of place. So she said they should not feel it necessary to come. I’m sure she meant it kindly, but of course…’

The dam of breeding and reserve that had sustained the dowager now broke with a devastating suddenness, leaving her shaking with misery and despair.

‘She means nothing kindly, Minna. Nothing! She is a hateful, spiteful, dreadful girl. And Rupert will never jilt her. From the age of three I’ve never known him break his word.’ Over the congealed crumpets she stretched a hand out to her friend. ‘Oh, God, he’s going to be so unhappy! What am I going to do, Minna? What am I going to do?’

Rupert had been closeted for nearly an hour with Mr Frisby, the senior partner of Frisby, Frisby and Blenkinsop, who had handled the affairs of his family for generations. The business was long and involved, for the documents relating to Rupert’s marriage needed expert and detailed scrutiny. There were the settlements drawn up by Muriel’s advisers to examine, there was a new will to be made and, in between, Mr Frisby’s congratulations and happy enquiries to receive. For of course Rupert’s marriage to an heiress could not fail to delight his solicitor, who for years had coupled deep respect and admiration for the Fraynes with anxiety about the state of their finances.

‘And how is Miss Hardwicke liking this part of the world?’ Mr Frisby asked now, while they waited for the clerk to bring in another box of documents.

‘Oh, very much,’ Rupert answered with his friendly smile.

He got up and moved over to the window, irked by the hours spent indoors on such a lovely day. The square was quiet in the early afternoon. An old woman sat on a seat sunning herself; a handful of children played hopscotch on the cobbles…

Suddenly, Rupert stiffened. A girl in a dark coat and skirt was hurrying in a purposeful manner across the far side: a girl whose quick, light walk as of an accidentally earthbound angel was appallingly familiar. Now she was slowing down, hesitating, standing looking upwards at the windows of a shop. He narrowed his eyes, making out the lettering.

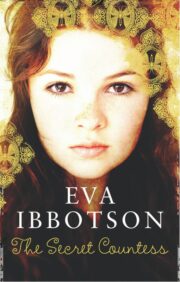

"The Secret Countess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Countess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Countess" друзьям в соцсетях.