Minna sighed. She had not told her husband what Muriel had said to Ollie, but the fear that Muriel had done some real and permanent damage to the child was always present in her mind.

Lord Byrne looked at his wife. He’d married her blind, knowing nothing about her except that she had a quiet voice, a sensible manner and some spare cash. Now, eight years later, he would have died for her without a second’s hesitation. To dress up as a hussar in Wellington’s army would be harder, but he would do it.

‘What about Tom?’ he asked. ‘Does he know about all this dressing up?’

Minna nodded. ‘I’m relying on Ollie to bring him round. Hugh’s the one who’s made most fuss. He actually got the headmaster to let him ring from Craigston to complain. The friend he’s bringing down doesn’t have anything to dress up in. So I said their cadet uniform would be all right.’

Lord Byrne nodded. ‘Rabinovitch won’t like it,’ he said darkly, allowing himself a moment of glee.

Lord Byrne was right. Rabinovitch didn’t like it. Informed by Hannah that he was to attend the ball at Heslop in fancy dress, Rabinovitch turned his liquid frog eyes on his wife and said: ‘Hannerle, make not the stupid jokes.’

‘I don’t joke, Leo. Minna has asked that we dress up. It is for Miss Hardwicke who wishes to be the Pompadour.’

‘And because some stupid shiksa wishes to be—’

‘Leo! Miss Hardwicke is a most charming girl.’

The conversation now descended into rapid and agitated Yiddish, ending, as was to be expected, in defeat for Leo, who agreed to add a red cummerbund to his evening clothes provided it was understood that this, and this alone, would turn him into a bullfighter.

‘But no sombrero! Absolutely no sombrero,’ said Leo, going down fighting.

Surprisingly it was Susie, usually so easy-going and uncomplicated, who proved difficult, stating that she had no intention of making a fool of herself to please that opinionated blancmange who had ensnared Rupert.

‘Susie!’ said her mother, deeply shocked.

But Susie, to whom Tom had fled after his day in London, was unrepentant. In the end, however, she too yielded, seeing how much it meant to her mother; for Hannah Rabinovitch, like Minna Byrne, was a woman who reaped as she had sown.

It was while Susie was bending her usual, quiet attention to the problem of whether she would look less ridiculous as a gypsy or a shepherdess, that a maid entered with a letter on a salver.

Hannah opened it. ‘It’s from Mersham. From Muriel,’ she said, pleased and eager, and began to read. ‘She thanks us most kindly for the wedding present.’

Leo, who had just paid the staggering bill for the six-hundred-piece Potsdam dinner service, was heard to murmur that he was glad to hear it.

‘What is it, Mother?’

Something in his daughter’s voice made Leo lift his head.

Hannah was standing by the window, the letter in her hand. She looked, suddenly, immensely, unutterably weary and as old as one of the mourning, black-clad women in the Cossack-haunted village of her youth. And indeed the hideous thing that had crept out from beneath Muriel’s honeyed, conventional phrases was as old, as inescapable, as time itself.

It is always a mistake to go back — and to go back to a place where one has been wholly happy is foolishness indeed.

Knowing this, Rupert was nevertheless badly shaken by the intensity of the memories which gripped him. He had survived well enough at Eton, but it was at Cambridge that he entered his heritage. It was here that he had discovered his passion for scholarship, here that he learned to excel at the solitary sports he so greatly preferred to the endless team games of his adolescence: here, above all, that he had learned the meaning of friendship.

Now, crossing Trinity Great Court, passing the shabby rooms on Q staircase with the carved motto on the mantelpiece (“Truth thee shalt deliver: it is no drede’) which had been his own, he walked through a gallery of ghosts. On the rim of this fountain, Con Grainger, deeply drunk and wearing striped pyjamas had declaimed, verbatim, Demosthenes’ Second Philip pic, before falling senseless into the water. Over that ridge of roof, now bathed in sunshine, Naismith, besotted with love for an Amazonian physicist from Girton, had climbed at night to hold hopeless court beneath her red-brick tower. Naismith had been killed outright within a month of reaching France — luckier than Con, perhaps, who still lay, shell-shocked and three-quarters blind in a Sussex hospital. And Potts, the brilliant biochemist who had kept a lonely beetroot respiring in a tank… Potts, who was a ‘conchie’, and had been handed a white feather by an old lady in Piccadilly the week before he’d taken his stretcher across the lines to fetch back one of the wounded and been blown to pieces by a mine…

Rupert walked on through the arch on the far side and made his way down to the river, only to be led by its lazy, muddy, unforgettable smell into another bygone world: of punts moored behind willows, of picnics at Byron’s pool — and girls.

But this, too, was forbidden country now and turning, Rupert made his way back to the master’s lodge, where he had been bidden to take sherry before luncheon at high table.

Later in hall, among the napery and fine glass, the ghosts crept quietly away. Here time really had stood still. Kerry and Warburger were still splenetically dismembering a colleague’s ill-considered views on Kant; Battersley was still laughing uproariously at his own appalling puns; the fish pie was still the best in England.

‘Coming back to us, then?’ enquired Sir Henry Forster, regarded by most people, himself included, as England’s foremost classicist. ‘Quite a good chance of a fellowship, I should think. I remember your paper for the Aristotelian Society. An interesting point you made there, about the morale factor in Horatius’s victory over the Curiatii.’

‘Keeping up your fencing, I hope?’ said the bursar, who had won ten pounds from his opposite number at Christchurch when Rupert and his team had taken the cup from Oxford.

Rupert answered politely, but his mind was already on his interview with the man he’d come to see. Professor Marcus Fitzroy was not in hall, because he despised food as he despised sleep and undergraduates and anything else which prevented him from getting on with the real business of life, namely the total understanding and expert disinterment of those distant and long-dead peoples whose burial customs so powerfully possessed his soul.

As soon as politeness permitted, Rupert made his way to the professor’s rooms in Neville Court. He found them marvellously unchanged. A shrunken head on the mantelpiece supported an invitation to a musical evening; jade leg ornaments, axes and awls, and Rupert’s own favourite, the skeleton of a prisoner immolated in the Yangtse Gorge, lay in their former jumble. Among the debris, a more recent strata of half-packed boxes, rolls of canvas and coils of rope indicated signs of imminent departure. The crumbling, highly archaeological-looking substance on a saucer seemed, however, to be the professor’s lunch.

‘You’re off tomorrow, then, sir?’ asked Rupert when greetings had been exchanged.

Professor Fitzroy nodded. He was a tall man, sepulchrally thin, with a tuft of grey hair which accentuated his resemblance to a demented heron. ‘Pity you couldn’t come,’ he said. ‘I’ve got to take that ass, Johnson.’ The professor’s contempt for students had not extended to Rupert, who, on a couple of undergraduate expeditions, had shown himself to possess not only physical endurance and the investigative acumen one might expect of Trinity’s top history scholar, but also something rarer — a kind of silent empathy with the tribesmen and mountain people they had encountered. That a man like this should be wasted on an earldom and a rich marriage seemed to the professor to be an appalling shame.

‘You’re making straight for the Turkish border?’ enquired Rupert, holding down the lid of a crate for the professor to hammer in.

‘Yes, it’s only a quick trip,’ said Fitzroy disgustedly, for his real passion was for the wastes of Northern Asia — and the Black Sea, professionally speaking, did not rank much above Ealing Broadway. ‘I’ve been landed with a field course back here in September; these damned ex-servicemen are so keen.’

‘You said in your letter you hoped to go up to the cave monastery above Akhalsitske?’

‘That’s right. It’s an extraordinary place — everyone seems to have been there. Alexander, of course, and then Farnavazi when he set up court at Mtskhet… And then there’s the Byzantine stuff plonked down on top of it all,’ said the professor, waving a dismissive hand at the modern upstart that was early Christendom. ‘I’m going to look at the rock frieze in one of the inner caves. I’ve been corresponding with Himmelmann in Munich and he’s convinced there’s a link there with the Phrygian tomb monuments at Karahisor.’

‘But surely, sir, that’ll take you across the Russian border? Isn’t there some fighting still going on there?’

The professor shrugged. ‘I don’t suppose it’ll bother me.’

Rupert thought this possible. Professor Fitzroy, who had carried a mummified goat across the Kurrum valley in Afghanistan while being shot at by both sides during the Ghilzai’s rebellion, would probably not be greatly troubled by the remnants of a Russian civil war. In addition to a total indifference to hardship and danger, the professor possessed a brother who was something very high up in the Foreign Office and of whom he unashamedly took advantage to get his archaeological finds back through customs including — so rumour had it — a beautiful Circassian wrapped in a camel blanket whom he was said to have installed in his house at Trumpington.

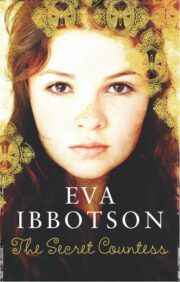

"The Secret Countess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Countess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Countess" друзьям в соцсетях.