By the time the dowager had soothed Miss Frensham she was late for her appointment with Colonel Forster at the Mill House and must, she realized, have made a mess of explaining why she had to move into the Mill House immediately without waiting for the improvements that the Forsters were so kindly putting in for her, because Colonel Forster had looked at her very strangely and Mrs Forster had patted her hand in quite the wrong way when she left. And when at last she had gone home and sat down for a moment to rest, there had been the usual psychic vibrations and the voice of Hatty Dalrymple had come through as clearly as if she were still beside her in the dormitory all those years ago at school. Hatty, who had passed over as the result of a boating accident at Cowes, had always been a gusher and the information that she could see rays of aetheric ecstacy emanating from Rupert and his lovely, lovely bride did little for the dowager, remembering the look in Rupert’s eyes these days.

And now she really had to make up her mind whether or not to send a wedding invitation to the Herrings.

Mr and Mrs Melvyn Herring and their twin sons, Donald and Dennis, were not so much herrings as sheep, and extremely black ones at that. The dowager came from an old Irish family whose pedigree was excellent, but whose upbringing, on a wild and lovely estate in County Down, had been unconventional and lacking in discipline. As a result, when the dowager’s youngest sister, Vanessa, fell passionately in love with the extremely handsome hairdresser who came to prepare her glorious, golden ringlets for her coming-out ball, she had put lunacy into action and eloped with him. For this attack of passion, poor Vanessa Templeton paid dearly, coming round, so to speak, a few months later — to find herself pregnant, penniless and desperate. Whether she died of a broken heart or puerperal fever following the birth of her son, Melvyn, it would be hard to say. Whatever the reason, there now began the long process of dumping Melvyn on anyone who would have him which was to take up so much of his father’s life. For Vanessa Templeton’s love child was one of nature’s genuine abominations: a deeply unpleasant child who grew in deceit, temper and general sliminess into the kind of adult who can empty a room within minutes of entering it. Melvyn’s sojourn at the Templetons’ estate in County Down was burned into the marrow of every one of its inhabitants, from Lady Templeton herself down to the obscurest scullery maid. The dowager, inviting him to Mersham in his early adolescence, had been harrowed by this resemblance and by the fact that he looked like a smeared and blotched version of her own Rupert. During this visit, Melvyn had (at the age of fourteen) got the stillroom maid pregnant, lamed George’s favourite hunter with an air gun and stolen a hundred gold sovereigns from her husband’s desk. During a second visit, at the age of sixteen, he had started a fire in the morning room with an illicit cigarette and left with his aunt’s favourite Meissen figurine, which he sold to a dealer before it could be traced. Fortunately, Nemesis overtook him in the form of a waitress called Myrtle who, finding herself pregnant by him, got him to the altar. The birth of Dennis and Donald squared the account for the twins, growing from pimpled, puking and overweight blobs of dough into pallid, whining mounds of flesh, finally put the Herrings beyond the social pale. No one felt able to invite four horrible Herrings to their house and, after an abortive attempt by the Templetons to ship them off to America, Australia — anywhere — the Herrings dropped into obscurity in a Birmingham suburb.

But Rupert’s wedding… The dowager, remembering her lovely, youngest sister, dangerously allowing sentiment to overcome reason, made up her mind.

‘I’ll ask them,’ she decided. ‘After all, Melvyn is my nephew.’

And so the gold-embossed invitation bidding Mr and Mrs Melvyn Herring and Donald and Dennis Herring to the wedding of Muriel Hardwicke with Rupert St John Oliver Frayne, Seventh Earl of Westerholme, in the church of St Peter and St Paul on the 28 July at 12.30 and afterwards at Mersham, dropped on to the threadbare linoleum of the Herrings’ hall in 398 Hookley Road, Birmingham — with consequences which no one, at this stage, could possibly have foreseen.

The wedding preparations now accelerated towards their climax. Carriers drew up, continuously, delivering antique wine coolers, famille vert bowls, ormolu clocks and a set of matching beermats showing views of the Hookley Road, which the Herrings, enchanted to be taken up again by their grand relations, had pilfered from their local pub. The Rabinovitches, exceeding even their usual generosity, sent a six-hundred piece armorial dinner service decorated in sepia and gold. Muriel moved among her wedding gifts with great efficiency, acknowledging everything meticulously as soon as it arrived and personally instructing Proom as to its display in the ante-room to the gold saloon. Old Lord and Lady Templeton wrote that they would come from Ireland. Minna Byrne most nobly offered to accommodate the Duke and Duchess of Nettleford and their four younger daughters, leaving only the Lady Lavinia to sleep at Mersham. The dowager wrote a friendly note to Dr Lightbody and his wife and was relieved, though surprised, that Muriel apparently had not one living relation who would wish to see her married.

But of course the bulk of the work fell on the staff. The influx of house guests for the wedding meant the opening up of rooms in the north wing and, once again, the maids were up at dawn, blackleading and dusting, washing the wainscot, taking curtains down and carpets up. Over the wedding breakfast itself, the dowager had made a stand. This was to be her last occasion as hostess at Mersham and there were to be no taboos. Only the best champagne and the choicest dishes would be served and, though there might be a few special alcohol-free dishes for Muriel and Dr Lightbody, everything else would be as fine as Mrs Park could make it. So there was singing again in the kitchen as the gentle cook broke thirty-three eggs into her big bowl for the wedding cake and Win’s round face beamed with relief, seeing her adored Mrs Park restored to happiness.

As for Rupert, he now did what troubled human beings have always done — he buried himself in work. Fortunately, there was enough of it. The estate had been neglected for years. Freed, now, from financial restraints, Rupert spent hours with his foresters, his farm manager, his bailiff. The new earl’s capacity for listening, his high intelligence and quick concern, were a boon to the men who worked for him. They brought him their plans and hopes, their troubles and their prejudices. As he walked through his forests, pored over drainage plans, discussed cropping programmes and roofing materials, Rupert was content. Only at night, in the little room in the bachelor wing which he still preferred to his now spring-cleaned master suite, did the facade crack and into the landscape of his earlier nightmares there entered a new figure: a still, dark-eyed girl who stood with bent head, waiting — and when he reached for her, was gone.

Then, with less than four weeks to the wedding, he suddenly announced his intention of going to Cambridge ‘on business’. While Muriel was still formulating her displeasure he had taken the Daimler and gone.

That afternoon, going into the housekeeper’s room to take tea as was his custom, Proom found Mrs Bassenthwaite sitting in her chair, doubled up and groaning with pain. The following day, in Maidens Over Hospital, she was operated on for the removal of her gall bladder.

At this crucial time, Mersham was without a housekeeper. Muriel saw this as her chance and, with characteristic efficiency, she took it.

10

Three days later, Mrs Park woke up aware that something was wrong. She looked at the round, brass clock on the chest of drawers. Half past six. Win should have been in half an hour ago with the cup of tea she always brought.

Mrs Park rose, put on her pink flannel dressing gown and carpet slippers and padded through her own snug sitting room behind the kitchens down the stone corridor to where Win slept, in a little slit of a room between the laundry and the stillroom.

There was no sign of Win. The bed was empty, the pillow uncreased, the grey blankets pulled tight over the iron bed.

Mrs Park’s heart began to pound. Instinctively knowing that it was useless, she went through the kitchens into the servants’ hall. The range had not been lit, the servants’ breakfast had not been laid. Still searching and calling she went through the sculleries, the pantries, the larder… In the sewing room she found Anna, changing out of her riding habit into her uniform.

‘Anna, Win’s gone! Her bed’s not been slept in!’

Anna turned, her cap in her hand. ‘It was her half-day off yesterday, I think? So she will have gone into the grounds, perhaps, and fallen asleep? The night was so beautiful. I have done this myself — often have I done it,’ said Anna, but her eyes were grave.

Within half an hour every single member of staff was searching for the little dimwit who was as much a part of Mersham as the moss on the paving stones. Mr Cameron and his underlings searched the walled garden, the greenhouses and the orangery — for Win had loved flowers. Potter rode off to scour the woods; James and Sid circled the lake.

By lunchtime it was clear that the matter was one for the police and Proom, his face more than usually grave, went upstairs to inform the family.

The dowager and Muriel were in the morning room. Rupert had not yet returned from Cambridge.

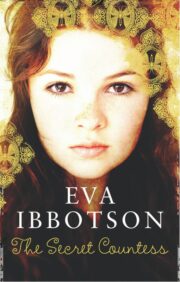

"The Secret Countess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Countess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Countess" друзьям в соцсетях.