Meanwhile Anna and the Honourable Olive had arrived downstairs and were wending their eager and interested way through the food hall. Tom’s plan had succeeded. In exchange for a promised taxi afterwards to take her to West Paddington, Anna had expressed herself delighted to deliver Ollie at Fortman’s. Now the two girls were sniffing their way appreciatively between jars of Chinese ginger, beribboned chocolate boxes, marzipan fruit…

‘Isn’t it a lovely shop, Anna!’

‘Beautiful!’ said Anna, her eyes alight. ‘How many things can you smell, Ollie?’

The little girl wrinkled her nose. ‘Cheese and coffee and a sort of sausage-ish smell and soap…’

‘And freesias and cigars and duchesses…’

Ollie giggled. ‘Duchesses don’t smell.’

‘Oh yes, they do,’ said Anna. ‘It’s a very rich smell with fur coats in it and lap dogs and blue, blue blood.’

They were still laughing as they went up in the lift, but as they approached the opulent silence of the bridal department and passed an amazingly disdainful looking dummy swathed in white tulle, Ollie suddenly became quiet, overcome by the importance of the occasion.

‘Could you… stay till Tom comes back?’ she asked, letting her hand creep into Anna’s.

Anna nodded, glad that she had not given Pinny a definite arrival time.

‘But of course.’

Madame Duparc, momentarily relegating Muriel to two minions, now came forward to welcome them. ‘Ah, this is the little flower girl for whom we have been waiting,’ she said, smiling down at the child with her flame coloured curls and brave limp.

‘Come, ma petite, your dress is ready. The others are next door so we will go into this room and give them a surprise.’ She turned to Anna, in no way deceived by the plainness of her clothes and said: ‘You will wish to accompany your little friend, mademoiselle?’

‘Thank you.’

Ollie stepped into the booth. Anna helped her out of her coat, her dress. Very small, utterly expectant, wearing her petticoat with real lace, the Honourable Olive stood and waited.

Then they came, two girls, ceremoniously carrying the ensemble that for weeks now had been the stuff of Ollie’s dreams. They carefully unwrapped the rose pink dress, the velvet cloak, the pearl-encrusted muff.

‘Oh, Anna, look!’ said the Honourable Olive, holding her arms up. ‘Oh, gosh…’

Next door things were proceeding less smoothly. Cynthia Smythe, it was true, oozed meekness and gratitude as she turned and twisted at the fitting girl’s behest and the Lady Lavinia, in her booth, staring over the heads of the assistants with the bored hauteur of a thoroughbred being decked out for a minor agricultural show, gave relatively little trouble.

The same could not be said of Muriel Hardwicke. Muriel had the clearest possible ideas about the way her dress and train and veil should look and these ideas, though she expressed them forcibly, the staff of Fortman and Bittlestone were failing to realize.

‘No, no… that dart is in quite the wrong place. And the sleeves are much too full at the wrist.’

‘But when mademoiselle has her bouquet—’

‘I’m not carrying a bouquet,’ snapped Muriel, ‘flowers are far too unreliable. I’m carrying a gold-bound prayer-book, so please don’t use that as an excuse.’

The girls grew hot and flustered, Madame Duparc’s varicose veins throbbed and pounded across her swollen legs… But at last, though grudgingly, Muriel declared herself reasonably satisfied.

‘If the others are ready, tell them to come out, please. I want to see the effect of the whole ensemble.’

The door of the left-hand booth now opened and there emerged, like one of the puppets in Petroushka, the apologetic and slightly goose-pimpled figure of Miss Cynthia Smythe.

The door of the right-hand booth followed — and the Lady Lavinia Nettleford, lofty and indifferent in her eighteenth bridesmaid’s dress, stepped out.

After which Madame Duparc, the little sewing girls and the chief vendeuse gave the same experienced and slightly weary sigh.

For her bridesmaids Muriel had chosen identical dresses of rose pink satin with a bloused bodice, a pink velvet sash and the three-tiered skirts which the great Poiret had just introduced in Paris. A wide frill of pink accordion-pleated chiffon lined the hems, encircled the cuffs of the short sleeves and edged the square neck — and dipping low on their foreheads like inverted tea cups, the girls wore close-fitting, pink satin-petalled caps.

Pink is a lovely and becoming colour and the image of a rose is never far from the minds of those who contemplate an ensemble of this shade. Unfortunately, there are other images which may intrude. Cynthia Smythe, emerging soft-fleshed, goitrous and apathetic from her ruffles, suggested a prematurely dished-up and rather nervous ham. The Lady Lavinia had other troubles. Though the bodice was generously bloused, the Lady Lavinia was not. With her stick-like arms, jerky movements and the tendency to whiskers which has been the Nettleford scourge for generations, she relentlessly reminded the onlookers that pink is not only the colour of budding roses, but of boiling prawns.

But now the door of the centre booth was thrown open and there emerged — to the sound of imagined trumpets — the bride herself.

Muriel had chosen not white, but a rich brocade of ivory which better took up the colour of her creamy skin. Cleaving to her magnificent bosom, clinging till the last possible moment to her generously undulating hips, the dress fanned out dramatically into a six-foot train, embroidered with opalescent beads and glistening pailettes. Richly elaborate threadwork also spangled the bodice and, eschewing the simple white tulle so beloved of ordinary brides, Muriel had set her diamond tiara over a veil of glittering silver lace.

And seeing her, Madame Duparc and her staff broke into the expected applause, but half-heartedly, for weddings were their business and Muriel, in her metallic splendour, looked more like some goddess descending from Valhalla than a bride.

A very small noise, like a cricket clearing its throat, caused them to turn their heads.

In the doorway leading from the other fitting room stood a tiny figure in rose pink satin — and pushed gently forward by Anna, who then stood aside — the Honourable Olive, en grand tenue, began to walk across the deep pile of the dove grey carpet towards Muriel and her retinue.

And as they watched her the tired sewing women began to smile, remembering suddenly what it was all about. The sheer joy of a wedding: the sense of wonder and humility and awe… the newness of it and the hope… all were there in this child, limping with a shining morning face towards the bride.

Holding in one reverent hand the flounces of her dress, clutching in the other the pearl-encrusted muff she had not been able to relinquish, Ollie advanced. Apart from a head-dress of fresh flowers for which Minna had begged, Ollie’s outfit was the same as the other bridesmaids’, but her radiance and delight had transfigured it. The pink ruffles nestled beguilingly against her throat; she listened with parted lips to the rustle of her skirt as if it were the sound of angel’s wings. One of the fitting girls, forgetting her place, had sent downstairs for rosebuds, which by some alchemy blended, instead of clashing, with her flaming hair.

Now Ollie was close enough really to see Muriel and the blue eyes widened behind the round glasses. Ever since she had heard Muriel spoken of, Ollie had seen her as a fairy tale princess. Here in reality, she surpassed all Ollie’s dreams. Untroubled by considerations of suitability or good taste, Ollie gazed at the glittering, shimmering figure with its diamond crown. And forgetting about herself completely, she came to rest in front of Muriel, looked up adoringly, and said:

‘Oh! You do look beautiful!’

Muriel seemed not to have heard. Ever since Ollie had appeared in the doorway she had been staring in silent fascination at the child. Now she drew in her breath and as Anna, guided by some instinct, stepped forward and Tom Byrne entered to fetch the bridesmaids, she hissed, in a whisper which carried right across the room:

‘Why did no one tell me that the child was crippled!’

8

Ollie had heard. As though the words had been a physical blow, the colour drained from her face, she bent her bright head and the small hand which had been proudly holding up the flounces of her skirt dropped to her side. In shocked silence, Madame Duparc and the shopgirls stared at the woman who had done this deed.

Tom Byrne had checked his first steps towards his sister to control a rage so murderous that it terrified him. He wanted to shake Muriel till her teeth rattled, to press his fingers into her throat. Horrified to find these feelings in himself, he stood stock-still in the middle of the floor like a bewildered bull.

It was the Lady Lavinia, with her well-bred indifference, who saved the moment by suggesting an alteration to Muriel’s train and the fitting continued.

But when it was over and it came to carrying out the next part of the programme, Ollie quietly refused to cooperate. To the suggestion that she should now join the other bridesmaids for luncheon at the Ritz, the Honourable Olive gave a low-voiced but unalterable ‘No’. She wasn’t, she said, hungry and, clinging to Anna’s hand, she added that she thought she would like to go home.

‘I can’t take you home yet, love,’ said Tom, desperately distressed — turning, with appeal in his nice brown eyes, to the Lady Lavinia Nettleford and Cynthia Smythe. Surely they would release him, let him attend to his sister? But in the eyes of Muriel’s adult bridesmaids there was only a desire, implacable as the urge of a wildebeest towards a water hole, for luncheon at the Ritz.

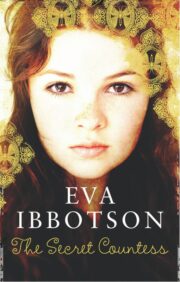

"The Secret Countess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Countess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Countess" друзьям в соцсетях.