‘No, please. I don’t want a drink. Just stay a little longer.’ One of her thick braids had come unplaited at the ends and he was reminded, foolishly, of the fronded bracken he had uncurled with his fingers as a boy. ‘Tell me about yourself. Where were you born?’

Relieved by the impersonality of the question, she said, ‘In St Petersburg. I can never think of it as Petrograd.’

‘Ah, yes. The city built on the bones of a thousand serfs.’

‘Yes, it was built by Peter’s dream and many people suffered for it. But it is not a sad city. The streets are so wide and the houses are such lovely colours: apricot and moss green and that colour that is like coffee with cream in it, you know? And everywhere there is water. The Neva, of course, and the canals, the Moika, the Fontanka… so that it’s as if there were mirrors everywhere and one can see two cities with golden domes, one floating over the other.’

‘Go on. Tell me about the snow.’

She smiled. ‘Ah, yes, the snow… We were always happy when the snow came, isn’t that ridiculous? But it made everything so smooth and quiet and… joined together. The whole city became one thing and the sledges were so swift and silent after the rattling of the droshkies. And in the country it was even better. We used to wait for the cranes to fly south and then we knew that in a very few days the snow would come. It has to fall three times before it lies, did you know that? The first fall melts and the second — but the third, that stays.’

She fell silent, her eyes full of memories, and Rupert, setting a trap for her, said quietly: ‘Qu’est-ce qui vous manque le plus?’

She frowned, thinking. Then, in a French more fluent and better accented than his own, she answered: ‘La sensation d’immensité, probablement. La Russie est si enorme que cela change tout.’

‘Yes.’ He could see that she might miss just those things: the sheer size of a land, its limitless skies, and the breadth of vision that such size might bring. And she had not even noticed the change of language!

Prompted by some demon to destroy the confidence he had carefully built up, he took hold of her wrist and said: ‘Do you realize if this were two hundred years ago I could keep you here? Exercise my droit de seigneur. What would you do then?’

‘I should scream,’ said Anna, disengaging her wrist. She got up and went lightly to the door, then she turned and said, grinning, ‘I ’ope!’ — and was gone.

The following day was a Sunday and the family had the pleasure of hearing Mr Morland read the banns and of introducing Muriel to those members of the congregation who had not managed to get a glimpse of her as she drove from the station. The future countess, in a Nile green satin suit and pearls, seemed relaxed and serene and bowed most graciously to her parishioners as she walked down the aisle. The earl, on the other hand, looked tired — but then he hadn’t been long out of hospital and men were always nervous about weddings.

It was also noted that very few Mersham servants were present. The dowager, unlike many employers, was not in the habit of marshalling her staff on a compulsory church parade. Today, most of the regulars had decided they could serve God best by staying at home and succouring Mrs Park.

The gentle cook had had a sleepless night and now sat like a broken-stemmed flower, reproaching herself, while Win, devoted and uncomprehending, tried to ply her with cups of tea.

‘It’s my fault; I should have found out,’ said Mrs Park. ‘Signor Manotti wouldn’t have done a thing like that.’

‘Give over, Jean, do,’ said James, abandoning protocol to use, for once, her Christian name. ‘Why, you know Signor Manotti had the brandy uncorked and half a pint in the bowl before ‘e even thought what he was going to cook.’

‘I just don’t know what to do,’ said Mrs Park in a low voice. ‘It’s everything, you see. No syllabub ’cos of the sherry, no jugged hare ’cos of the wine. No trifle, no crepes Suzettes… No beef stews, no coq au vin… Why, even Welsh Rarebit’s got ale in it.’

And as she sat there, seeing the whole rich vocabulary of dishes she had striven so hard to learn brought suddenly to nought, a large tear gathered in Mrs Park’s round, blue eyes and rolled slowly, unheeded, down her cheek.

It was too much for the others. ‘But she will not want you not to cook most beautifully for everyone else!’ cried Anna. ‘It is impossible that she does not want others to eat as they wish. It will only be necessary to prepare something extra that has no alcohol in it for her, and as she is very rich and there are many more people to help you, this will not matter.’

‘Anna’s right,’ said James. ‘Don’t you remember old Lady Byrne? She was a Quaker, never touched a drop herself but kept one of the best tables in the country.’

But Mrs Park was not to be consoled. Though trained by a great international chef, she belonged to the old-fashioned country tradition which bound a good cook, by a thread of skill and understanding, to the mistress of the house. Muriel’s rejection had left her desolate.

‘I’ll have to give in my notice, Mr Proom,’ she said. But even as she spoke, she looked at Win standing hunched and bewildered by the range. At the orphanage they had said Win was unemployable. ‘Defective’ was the word they used — a word that made no sense to Mrs Park, whose patient, loving kindness had turned the girl into a second pair of hands. But would a newcomer be able to take her on? If she herself left Mersham, what would become of Win?

And worn out by strain and sleeplessness and disappointment, Mrs Park let her head fall on her arms, and sobbed.

‘So these are your ancestors?’ said Muriel, looking with pleasure and interest at the serried ranks of Westerholmes in the long gallery.

Returning from church, she had found laid out for her a simple dress of blue linen which matched the colour of her eyes. She had taken the hint and also allowed Anna to arrange her golden hair in a low chignon. Steering her through the armoury, the library and the music room, Rupert thought he had never seen her look fresher or more beautiful and his misgivings of the previous night vanished in the sunlight. Of course Muriel would fit in at Mersham, of course she would love his people and his home.

‘Yes, those are the Westerholmes and the women fool enough to marry them,’ he said, smiling. ‘That’s Timothy Frayne, who founded the family fortune in all sorts of disreputable ways. And that’s his son, James — he was the first earl. James was one of the fair, roistering Fraynes, always in trouble! Then this one’s William — he’s one of the other kind, dark and dreamy. William landscaped the park and furnished the music room — music was his passion. And George here is a throwback to James — a devil with the women and always getting into scrapes. My brother was like him, they said.’

‘And you’re like William,’ said Muriel, looking at the scholarly face above the lace collar. ‘Goodness, who’s this one? He looks very strange!’

Rupert grinned. ‘That’s our black sheep, Sir Montague Frayne. He was a cousin of the fourth earl’s. He’s the only one of my ancestor’s who’s had the distinction of becoming a fully fledged ghost.’

‘Really?’ Muriel’s tone was not encouraging. ‘What did he do?’

‘He murdered his wife’s lover,’ said Rupert, looking at the wild-eyed young courtier nonchalantly posed with one hand on his hip. ‘Or the man he believed to be his wife’s lover: a young architect who built the Temple of Flora and the gothic folly in the woods.’

‘And where does he do his haunting?’ said Muriel, humouring her fiancé, for she did not, naturally, believe in ghosts.

‘Oh, not in the house. Out in the folly where the dark deed was done. It’s quite a big place, a sort of tower with three rooms one on top of the other with a dome on the top. No one uses it now and it’s kept padlocked. The servants swear he howls and wails in repentance, and of course no one will go near it in the dark.’

‘One must allow for foolishness and superstition in the uneducated classes,’ said Muriel.

‘Yes, I suppose one must,’ said Rupert, a little bleakly.

He looked at his watch. In an hour, Potter would be back with the mare. The excitement in the groom’s voice on the telephone had told Rupert all he wanted to know and, at the thought of the gift he was giving Muriel, his spirits soared. He had taken so much from her already, was so greatly in her debt, but the bridegroom’s present to the bride would at least be a worthy one!

‘Shall we go outside?’ he suggested. ‘You must have seen enough of my ancestors to last you a lifetime.’

‘Not at all, dear,’ said Muriel, who was peering intently at the portraits, ‘I find them very handsome.’ She turned to smile coquettishly at him. ‘Just like you. And there don’t seem to be any taints or blemishes, which is unusual in so old a family.’

‘Taints?’ said Rupert, puzzled. ‘What exactly do you mean?’

‘Well, you know… deformities, inherited diseases,’ said Muriel, drawing her skirt away from Baskerville. ‘Hare lips and so on,’ she continued. ‘Or mental illness. Though that would hardly show up in a painting, I suppose.’

Rupert was looking at her in rather an odd manner. ‘I don’t know of any; they were a very ordinary lot as far as I know. But if there were, Muriel, would it really matter to you?’

Muriel smiled and patted his arm with her plump, soft hand. ‘You must remember my great interest in eugenics. And once you have met Dr Lightbody, which I hope will be very soon, I know you will become as interested as I am.’

As they walked towards the garden door they met Pearl, carrying coals to Uncle Sebastien’s room.

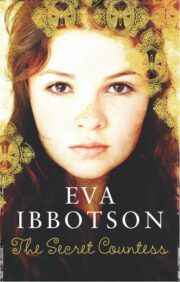

"The Secret Countess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Countess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Countess" друзьям в соцсетях.