Minna looked anxiously at her stepson. On all other matters Tom was easy-going and courteous, but on this particular subject…

Muriel, however, realized she had gone too far. ‘No, of course not. I just thought they might be embarrassed over dietary problems and so on.’ She laughed charmingly. ‘I wouldn’t like to make a mistake and offer them pork!’

‘They’re not strictly orthodox any more,’ said Minna, ‘though they kept the festivals for Leo’s mother while she lived. In any case,’ she went on, striving for lightness, ‘Proom knows everyone’s foibles. It isn’t Mersham they’ll envy you for after your marriage, Muriel — it isn’t even Rupert — it’s Proom!’

And as though on cue, Proom himself appeared in the double doorway and announced that supper was served.

The guests had eaten, the covers had been removed and now, in the majesty of polished satinwood and gleaming silver, the Westerholmes and their chosen friends awaited the climax of the evening, Mrs Park’s chef- d’oeuvre, the dessert she had created in homage to Muriel Hardwicke.

Below stairs the atmosphere was tense, fraught with the anxieties that attend the launching of a great ship. But the swan, on its gigantic platter, held steady as James lifted it, his scrupulously tended biceps never more worthily employed. Win, her mouth agape, ran to open the door; Louise bundled Mrs Park into a clean apron, ready for the expected summons…

‘The Mersham Swan, my lady,’ announced Proom — and as James marched forward to set the bird down before Miss Hardwicke, the guests rose to their feet and clapped.

‘My dear, what a triumph!’ said Minna Byrne. ‘Really, there is no one in the world like your Mrs Park!’

‘Oi, but that is genius!’ cried Hannah Rabinovitch, while Miss Tate and Miss Mortimer, the pixillated spinsters, hopped like little birds.

Proom, like a great conductor, waited in silence for silence. Then he took up the knife and, with a flourish which nevertheless contained no hint of ostentation, pierced the noble creature’s heart. Exactly as Mrs Park had foreseen, the filling, softly tinged with the pink of an alpine sunset, oozed mouthwateringly on to the plate. Deftly, Proom scooped out a piece of meringue breast, a section of almond-studded wing and with a small bow handed the plate to Muriel Hardwicke.

Everyone smiled and waited and Anna, standing in the doorway with her tray, gave the exact sigh she had given when, at the age of six, she saw the blue and silver curtains part for the first time at the Maryinsky.

Muriel picked up her spoon in her soft, plump hand. She raised it to her mouth. Then she made a little moue and put it down again.

‘You must forgive me if I leave this,’ she said, turning to the dowager.

The stunned silence which followed the remark was total.

‘You see,’ Muriel explained with a charming smile, ‘it has alcohol in it.’

Muriel was correct. There was alcohol in it. The Imperial Tokay Aszu 1904 which Proom, yielding to Mrs Park’s palpable need, had after all allowed her to have.

The dowager, after an agonized glance at her butler, seemed to be in a state of shock. By the doorway, Anna and Peggy made identical gestures, their hands across their mouths. Proom’s face was as sphinx-like as ever, but a small muscle twitched in his cheek.

Something about the atmosphere now made itself felt, even by Muriel. She turned to her fiancé.

‘You don’t mind, I’m sure?’

Rupert tried to pull himself together. ‘No… no, of course not. I knew you didn’t drink wine or spirits but not that even in food…’ He broke off as the full implications of Muriel’s embargo sank sickeningly into his brain.

‘Dr Lightbody showed me a piece of cirrhosed liver once. I have never forgotten it,’ said Muriel simply.

But now the shock which had held the guests silent began to wear off. Each and every person present had a memory of some good deed done by Mersham’s gentle, well-loved cook and, led by Minna Byrne, with her fine social sense, they threw themselves on to the dessert, begging and imploring Proom for helpings of the bird. The vicar, Mr Morland, remembering the feather-light delicacies the cook had sent down during his wife’s last illness, disposed of the swan’s neck and beak in an instant and asked for more. Tom Byrne, whose childhood visits to Mersham had always taken in a session of ‘helping’ in the kitchens, however busy Jean Park might be, consumed virtually an entire wing in fair imitation of Billy Bunter. Hannah Rabinovitch, though it cost her dear, abandoned her guard on the tenuous, pitted organ which served her husband for a stomach and allowed him to consume lethal doses of crème Chantilly…

Downstairs, Mrs Park sat in her clean apron and waited. Waited for ten minutes, for twenty, her eyes on the bell board, while hope and confidence and anticipation slowly drained away.

Until Proom himself, believing concealment to be impossible, came down and broke the news.

6

The night after the engagement party, Anna could not sleep. She had been on her feet from six in the morning until midnight, and even then Miss Hardwicke had expected her to wait up and help her into bed. By the time she reached her attic, Anna was in that state of exhaustion in which sleep, though desperately desired, is impossible to reach.

For a while she endured the heat and stuffiness of the little room, tossing and turning in the narrow bed. Then she gave up, slipped back the covers, and throwing a cotton shawl over her shoulders, began to creep quietly downstairs.

On the second floor landing she stopped abruptly. Here the back staircase crossed a panelled corridor on which were a series of small guest rooms used for visitors who came for shooting parties: simple, bachelor rooms that she had hardly seen.

And from behind the door of one of these had come the sound of someone moaning, as though in pain.

But who? Surely the rooms were empty? And then she remembered. The earl had moved into the end one temporarily while the grand master suite was being spring-cleaned for the wedding.

The sound came again: a low cry, followed by a spate of indistinguishable words. And, hesitating no longer, Anna pushed open the door.

By a shaft of moonlight coming from the uncurtained window she could make out a tousled head on the pillow. The Earl of Westerholme was groaning. He was also fast asleep. In familiar country now, Anna moved over to the bed and switched on the lamp. Then she leant over and shook her employer’s shoulders.

‘Wake up,’ she said. ‘Please wake up. Completely.’

Rupert opened his eyes, but the slim figure in white with the heavy braids of hair made no sense to him.

‘It is very foolish to sleep on your back,’ Anna said firmly. ‘It is always foolish, but when you have been in a war it is foolish beyond belief.’

The earl looked at her with unfocused eyes. He put out a hand and as he found hers, small-boned, infinitely flexible and rough as sandpaper, recognition came.

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘You. Of course.’ Then, suddenly ashamed, ‘I’m sorry. A nightmare…’

‘What was it about?’

The earl shook his head.

‘Yes,’ said Anna firmly. ‘You must tell me. I always made Petya tell me his dreams and then he was better.’

‘Who is Petya?’

‘My brother. He used to see anarchists on the ceiling. There was an icon lamp in his nursery which threw shadows. Tell me about your dream.’

‘It’s always the same. It’s after the crash… I was a pilot in the war, you see.’

She nodded. ‘I know.’

‘I’m in the tree… hanging,’ Rupert went on, speaking with difficulty, ‘and he’s down there on the grass, dry grass like Africa, and the flames are crackling. He’s on fire, burning like a rick. I try to get to him. I have to.’

‘Who is he?’

‘Johnny Peters. My navigator. I’m responsible for him.’

‘And then?’

‘I struggle and struggle, but the cords of the parachute are tangled round my neck and I know if I cry out… If I warn him, the flames will go out and I try to call but nothing comes.’

Anna’s work-roughened hand still rested in his. ‘Was it really like that?’

‘Yes… No… A little. He was burned earlier, in the plane. The flames weren’t like that. It was muddy… a turnip field. The flames are a pyre.’

‘Yes, I see. All men dream like that, I suppose, after a war. Women, too,’ she added ruefully. ‘It will be better when you are married.’ Suddenly she freed her hand and said eagerly: ‘Of course! How stupid I am! I will fetch Miss Hardwicke — she will want to be with you.’

‘No!’ Rupert was wide awake now, sitting up. ‘Good heavens, no! It would be most improper.’

‘Improper?’ said Anna, shocked. ‘She will not think of that when you are troubled.’

‘Anna, I forbid it,’ said the earl. ‘I’m all right now. I’m fine.’ But as she made as if to go he said pleadingly, like a child, ‘Stay a little longer. Tell me about your father.’

She smiled, her face tender in the lamplight. ‘I wish you had known him. He could make just being alive seem like an act of triumph. People used to smile when they saw him coming… he made everything all right.’ She swallowed. ‘He was in the Chevalier Guards,’ she went on, letting pride overcome caution. ‘It was one of the tsar’s crack regiments. When the revolution came the men mutinied and killed their own officers, so we tried to be glad that… he died when he did.’

‘What was his name?’

‘Peter Grazinsky. He was a good man and he hated war.’ She jumped up. ‘And now I’ll make you a hot drink and then—’

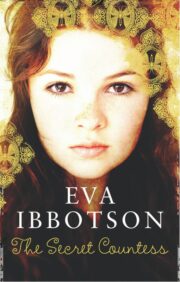

"The Secret Countess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Countess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Countess" друзьям в соцсетях.