‘Anna!’ Louise had long since made her peace with the Russian girl, but there were words which, as head housemaid, she had no intention of permitting her underlings to use.

‘I’m sorry,’ Anna apologized. ‘If I say chest blisters is it all right? So he went to see a professor of eugenics in Kazan and—’

But Anna’s account of the chicken farmer’s triumph in eliminating breast blistering was destined to remain unfinished. For Mrs Park, who had been lingering in the kitchen, now arrived at the door, shy and blushing like a bride, and said with simple dignity: ‘Will you come, everybody, and see…?’

Among her other anxieties, Mrs Park suffered from the conviction that guests at Mersham were in danger of starving to death. For the fifteen or so intimate friends invited that night to a buffet supper to celebrate the earl’s engagement, she had prepared three freshwater salmon grilled and garnished with parsley butter, a mousseline of trout adorned with stuffed crayfish heads and a pike poached in court bouillon. There was a fricassée of chicken with morels and cream, half a dozen ducklings, a York ham and a piece of boeuf royale which took up the whole of a side table…

But it was none of these that held the servants’ gaze. For, in the centre of the huge table, drawing the eye as inevitably as the Winged Victory compels the eye of those ascending the main staircase of the Louvre, was the dessert that Mrs Park had created in homage to Muriel Hardwicke.

The gentle cook had seen in her mind’s eye a great swan made of snow-white meringue — The Swan of Mersham, which was part of the Frayne coat of arms. She had visualized its wings made of the palest almonds, furled and slithered to feathered authenticity and its beak and eyes picked out in silver. She had imagined the inside of this mighty, heraldic bird as consisting of the most delicate and subtle mousse Bavarois which, at the touch of a knife on the creature’s heart, would ooze out in a fragrant mouthwatering slither… She had conceived of a great lake of crème Chantilly with islets of whipped syllabub for the swan to float upon and, surrounding it, an emerald shore of fringed angelica…

And what she had seen she had created.

For a moment, the servants marvelled in silence.

‘You’ll be sent for after this, Mrs P,’ said the butler, ‘so make sure you’re ready to go upstairs. Miss Hardwicke’ll want to see you, no doubt about it.’

‘Oh no, surely?’ Mrs Park, flushing rosily, demurred.

But secretly, modest as she was, she did think she’d be sent for. The swan had kept her and her devoted amanuensis, Win, from their beds for the best part of a week; but for once it seemed to her that she had made something of which Signor Manotti himself need not have been ashamed.

At Heslop Hall, Lady Byrne, already dressed for the party, was saying goodnight to Ollie, sitting like a small sunflower in her white-canopied bed.

When she had first come to Heslop, Minna Byrne had left untouched the bleeding stags, dismembered antlers and dripping, severed heads of John the Baptist which adorned the halls and corridors of Lord Byrne’s enormous Elizabethan mansion. But when she had discovered that her infant stepdaughter was supposed to sleep under a malodorous tapestry of St Sebastian being quite horribly stuck with arrows, Minna had acted with decision and despatch. Ollie’s room was now simply furnished, but looked delightful with its American patchwork quilt, bentwood rocking chair and gaily painted chests and it was there that the Byrnes tended to congregate at the end of the day.

‘You look lovely, Mummy,’ said Ollie.

Minna smiled. She always dressed plainly and had retained the Quaker air she had brought from her New England childhood. But for Muriel Hardwicke, who had saved Mersham from ruin and chosen Ollie for her bridesmaid, she had added the Byrne pearls to her cream silk dress and put diamond drops in her ears.

‘I wish I could come,’ said Ollie wistfully. ‘I haven’t seen Muriel yet.’

‘I know, lovey. But it’s really a very late party.’ While encouraging Ollie in every way to be independent, Minna secretly guarded her like a lioness against fatigue. ‘You’ll meet Muriel next week when you go to fit the dresses.’

‘Yes.’ Ollie gave a blissful sigh. Heslop had of late abounded in trapped housemaids pinned against walls, resigned under-gardeners and delayed tradesmen, all receiving, at Ollie’s hands, the details of her outfit.

Tom Byrne now wandered in in his evening clothes, to ruffle his sister’s hair and receive her compliments on his appearance.

‘You look very cheerful,’ said Minna, smiling at her eldest stepson.

Tom grinned. ‘I am. I can’t wait to meet this paragon of Rupert’s. Beautiful and devoted and saved his life and an orphan so we can have the fun of the wedding down here! It seems almost too good to be true. Not that anything’s too good for Rupert.’

‘No, he’s a dear and just the person for Mersham,’ said Minna, to whom Rupert’s war record had come as no surprise. ‘And Mary seems to have quite abandoned all those spirits of hers now he’s home and there’s a wedding to plan for.’

‘Well, not quite,’ said Tom. ‘Last time I called I had to take a message for Mrs MacCracken at the schoolhouse from a Passed-On Lady who was having trouble with her knitting on the other side.’

Minna sighed. She dearly loved the dowager, whose kindness when she first came to Heslop had been unceasing, nor was she disposed to mock anyone who sought comfort in the knowledge that the death of the body is not the end. If only the spirits, just once in a while, would come up with something interesting.

‘You won’t forget to give Anna the letter I wrote?’ Ollie asked her brother. ‘It’s very important. It’s all about the hedgehog.’

‘I won’t forget,’ promised Tom, looking tenderly down at the little marigold head.

‘What an interesting girl she sounds,’ said Minna. ‘Is she really Russian?’

‘So I understand.’

‘What a hard time they must have had, all those poor people. I was wondering whether I might ask Mary if she’d let me borrow her for the ball. I’m going to ask some of the Ballets Russes people down; leaven up the County a bit. A Russian maid would be invaluable. Remind me to mention it.’

‘All right, Mother. Oh, by the way, are you and Father going in the Rolls tonight?’

‘I imagine so. Why?’

‘I thought I’d take the Crossley over to the Rabinovitchs and ask them if they’d let me pick up Susie.’

Tom spoke as naturally as if his courtship of Susie Rabinovitch had not set the whole neighbourhood by the ears. When Tom had first clearly shown his interest in the plump and outwardly unprepossessing daughter of a Polish Jew, Tom’s father had not been pleased. Lord Byrne personally liked Leo and Hannah Rabinovitch, who, having amassed a fortune in the rag trade, had settled in a large and mottled mansion called The Towers a couple of miles from Heslop. All the same, it had been with some force that Lord Byrne had pointed out the presence in the neighbourhood of the Honourable Clarissa Dalrymple, of Felicity Shircross-Harbottle and a score of other girls left bereft by the loss of so many of their future husbands in the war. Tom, with his nice smile, had acknowledged their worth and continued to court Susie.

Gradually the Byrnes, led by Ollie, who thought The Towers, with its gilt bathrooms, thick, plush carpets and lamps shaped like swans, to be the most beautiful home she had ever seen, came to see Tom’s point of view. Exactly what it was about Susie was hard to say, but not to like her was impossible. It was therefore with slight chagrin and considerable amusement that the Byrnes watched the dismay that Tom’s courtship had evoked in Mr and Mrs Rabinovitch. Confronted with the despairing remnants of Jewish orthodoxy, the Byrnes could only smile and wait. Tom was twenty-five, Heslop was entailed and even if it hadn’t been, Lord Byrne would not have dreamt of dispossessing a son whom he loved deeply and who was eminently suited to succeed. For the rest, time would tell.

This philosophical attitude was not one that came naturally to Hannah Rabinovitch, dressing for the engagement party in her bedroom at The Towers, which she had furnished, in all innocence, like a luxurious brothel of the Belle Époque. The thought that Tom Byrne, as Rupert’s best man, would be very much in evidence that night brought a frown to the kind, middle-aged face which she was methodically rubbing with cold cream.

How had it happened? Why did good-looking Tom Byrne, the heir after all not only to a viscountancy but to a considerable fortune from his delightful American stepmother, have to fall in love with Susie? And, as if to find some clue to the secret, Mrs Rabinovitch pulled her wrapper closer and went into her daughter’s room.

Susie’s maid was busily laying out the red lace dress, the kid shoes and embroidered shawl that Susie was to wear that evening. Susie herself, quite oblivious of these preparations, was curled up in an armchair reading The Brothers Karamazov. As she looked at her only daughter, Hannah shook her head and sighed.

For Susie was plain. Not perhaps ugly, though she had been spared neither the big nose nor the frizzy hair which so often characterized her race, but undoubtedly plain. Plain and plump and bookish to a degree that surely should have put off an attractive young aristocrat who had practically been born on a horse. What right had Tom Byrne to discern, within a month of their meeting, that Susie had a heart of gold, a sterling sense of humour and the kind of creative common sense that can smooth out personal crises in a moment? So Susie was the light of their life, the joy of their declining years — but what business was that of Tom Byrne’s? Why hadn’t he and his family cut them dead when they moved into the district? A Jewish rag trade merchant like her Leo? Not only a Jew, but a Polish Jew, who, everyone knew, was the lowest of the low?

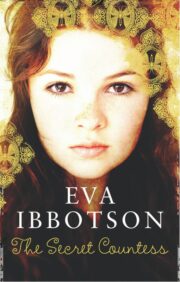

"The Secret Countess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Countess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Countess" друзьям в соцсетях.