Somehow she didn’t look like a Muriel? But why?

Later that evening, Anna received a summons to the dowager’s room.

It was a critical time below stairs, for Mrs Park was planning a brand-new dessert for Miss Hardwicke’s engagement party. This concoction, which had been stirring in her mind since the engagement was announced, was nothing less than a great swan made of meringue. But inside the swan — a challenge not to be denied — she wanted to put a filling of crème Bavaroise. And for this she knew (with her instinct and her fingertips, as she knew everything) she would need a cupful of Tokay. What’s more, not just any Tokay, but the 1904 Aszu puttonyos, which alone combined the necessary delicacy with a touch of earthiness. Proom was being uncooperative about supplying this admittedly priceless wine, declaring that it was absurd to open a whole bottle of the stuff just for a few spoonfuls.

When she was compelled to do with lesser ingredients, Mrs Park never sulked, but she nevertheless suffered and her suffering was reflected in Win’s uncomprehending and adenoidal melancholy and a general ‘atmosphere’, which prevented Sid from whistling and James from giving his biceps their usual evening canter down his forearm.

But when Anna’s summons came, the kind cook was able to put her own troubles aside for a moment.

‘Now don’t look like that, dear,’ she said encouragingly. ‘It’s nothing to be afraid of, I’m sure.’

Mrs Park was right. The dowager had sent for Anna to inform her that she was to wait on Rupert’s fiancée till a new lady’s maid should be engaged.

Anna stared at her, her huge, tea-coloured eyes turning quite stewed with despair.

‘But I do not know enough to do this, my lady!’

‘Nonsense, my dear, I’m sure you’ll do it splendidly.

Mrs Bassenthwaite speaks very highly of your work.’ ‘But in Selina Strickland there are terrible things in the part concerning lady’s maids. Like… for example, gophering irons. I do not know,’ said Anna desperately, ‘how to gopher!’

The countess was unimpressed. ‘I think that must be rather an old-fashioned book, dear,’ she said. ‘And anyway, my maid, Alice, will be only too willing to advise you. It’s just to help Miss Hardwicke dress and keep her room tidy and bring her breakfast tray. Proom will explain your duties, but I assure you there’s nothing that’s at all difficult.’

Anna, however, was hard to console and returned to the kitchen in a state of dejection which it took the combined efforts of Mrs Park, James and Louise to overcome.

‘For heaven’s sake, it’s an honour,’ said Louise. ‘Why aren’t you pleased?’

Anna launched into an explanation, from which the bewildered servants gathered that she was afraid of becoming like some character in a book who had been tossed up by the earth and rejected by the heavens.

‘Shall I still be able to have my meals downstairs?’ she asked tragically.

It was Proom himself who disposed of Anna’s fears of a life spent in limbo, informing her that she was still a housemaid who would be expected to carry out her usual duties, as well as lending her services to Miss Hardwicke when required, adding that if she had nothing better to do she could go and see to the shutters as it was coming on to rain.

It was not only in the house and in the gardens that preparations were being made to welcome the new bride. Potter, the head groom, had been entrusted by his lordship with a commission that brought a spring to his step and sent him whistling round the stables. He was to purchase a mare for Miss Hardwicke’s use. And not just any mare — but one of Major Kingston’s white Arabs from the stud in Cheltenham that was the envy of the world.

‘Pay anything you like, Potter,’ the earl had said before he left for London. ‘It’s the bridegroom’s present to the bride and to hell with being sensible. We may be broke, but we’ll hold our heads high over this one.’

So Potter, leaving for Gloucestershire, was a happy man. Only the earl’s old hunter, Saturn, and the dowager’s carriage horses now remained of the fine stables they had kept before the war. Potter himself had been wise, refusing to join in the traditional battle of groom against chauffeur. He had learned to drive and been as willing to convey the dowager to the station in the Rolls as to drive her to the village in the brougham she still preferred when paying calls. But now he saw good times ahead for the new earl who, for all his quiet ways, was a brilliant horseman and, as he called in at the kitchens to say goodbye, there was pride in Potter’s bearing and a sparkle in his eye.

‘It is like a fairy story,’ said Anna, who had got over the shock of her promotion. ‘Three presents for the bride: a white rose, a dappled mare, a snowy swan… and now she comes!’

‘Let’s hope she’s a bloomin’ princess, then,’ said Louise, whose feet were hurting her, ‘or there’ll be ructions!’

4

Muriel Hardwicke had been, quite simply, a perfect baby. Born to parents already rendered wealthy by the gratifying sales of Hardwicke soups, Hardwicke sausages and a similar assortment of canned goods, her plump, pink limbs, golden curls and hyacinth-blue eyes were the wonder of all who beheld them. Her mother, an unremarkable and rather nervous woman, never ceased to be amazed at the physical perfection of her child; Muriel’s father, as though to prove himself worthy of what he had produced, redoubled his efforts at work, made mergers, formed companies and quite quickly became a millionaire.

Only Muriel herself, gravitating naturally to the ornate mirrors in the plush Mayfair mansion where she grew up, was not surprised at the flawlessness of the image which greeted her. It was as though she knew from the start that she was not like other children. She hated to be dirty, could not bear mess or torn clothes and once, when a stray kitten brought in by the cook scratched her hands, she shut herself in the nursery and refused to come out until it was removed.

She had reached a full-breasted and acne-less adolescence when her mother, as though she knew she could do no more for her lovely daughter, contracted pneumonia and died. Five years later, her father collapsed at a board meeting with a perforated ulcer and, at twenty-two, Muriel Hardwicke found herself sole heiress of a group of businesses valued at some three million pounds.

She did not let it go to her head. She kept the Mayfair house, engaged a chaperone and — the year was 1916 — herself volunteered as a VAD. Her loathing of illness and her detestation of squalor were put aside in the interests of her grand design. For now was the chance to cross the great barrier between the nouveau riche and the aristocracy. In the war hospital, with a steady stream of wounded officers passing through her hands, she would — she was quite certain — find a worthy mate.

In the event, it had taken two years; but when the Earl of Westerholme was wheeled in she had known her quest was ended. The title was an excellent one, the young man was undeniably attractive and his wounds, though severe, were not disfiguring. Nor did the fact that Mersham was impoverished displease her: it would make her own position more secure, for his family would welcome a bride who was going to restore their home.

Muriel’s own taste would have been for a fashionable wedding in a London church, but she had been quite happy to agree to Rupert’s offer of Mersham and a village wedding. For, studded about in impossible Yorkshire hovels which they refused to quit, were some ancient and deeply unsuitable relations of her father’s. Grandma Hardwicke with her rusty bonnet and clacking teeth might have dared to brave a big London church, but she would hardly turn up, uninvited, at Mersham. And after all, even a simple country wedding could be conducted with order, propriety and style.

This being so, Muriel was determined to make a clean start. Her house was to be sold, her servants dismissed. Only her chaperone, Mrs Finch-Heron, would travel with her to Mersham and then she too would be sent away.

But first she would go and say goodbye to the man who had clarified all her aspirations, the man whose ideas had come to her as though all her life had been leading towards such a goal. Dr Lightbody was giving a lecture tonight at the Conway Hall. She would go to it as a perfect preparation, a kind of blessing on her new life. And tomorrow, Mersham.

Slipping into her seat, Muriel noticed with irritation that the hall was half-empty. It was truly appalling what this gifted, handsome man had had to endure in the way of calumny and indifference. Dr Lightbody had a Swedish grandmother from whom he had inherited his fair hair and pale blue, visionary eyes. A devoted grandson, the doctor had most naturally decided to visit the old lady on her farm near Lund. The fact that his departure for Sweden happened to take place just two days before the outbreak of war was obviously a complete coincidence, yet there were people vile enough to accuse him of cowardice. The Swedes themselves had been so unreceptive to the implications of his ‘New Eugenics’ that the poor man had had to uproot himself immediately after the armistice and return to England.

And yet his doctrine was as uplifting as it was sensible and sane. Briefly, the doctor believed that it was possible, by diet, exercise and various kinds of purification about which he was perfectly willing to be specific when asked, to create an Ideal Human Body. But this was not all. When his disciples had made of their bodies a fitting Temple of the Spirit, it was also their obligation to mate with like bodies. In short, Dr Lightbody wished to apply to human beings those laws which farmers and horse breeders have used for generations. For as the great man was now most persuasively arguing, what was the use of producing swift racehorses, pigs with perfectly distributed body fat and chickens whose egg-boundedness was only a distant memory — while permitting the human race to perpetuate idleness, physical deformity and low intelligence by unrestricted breeding?

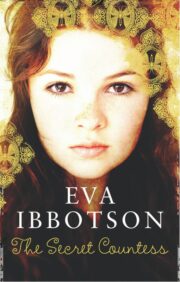

"The Secret Countess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Countess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Countess" друзьям в соцсетях.