Alice’s head was spinning. She thought of the note, crumpled in the pocket of her skirt. “You mean that you knew Lydia was at the windmill-”

“Lydia was never at the windmill,” Faye said sharply. “Really, Miss Lister, I thought that for all your dreadfully low antecedents you were still a clever girl! Did you not guess? The note was from me. I can do a fair copy of Lydia’s hand.”

Alice stared. Her heart had started to thud against her ribs. Her head was aching all of a sudden. The carriage had picked up speed without her noticing. It was ricocheting along the rutted country lane, rocking wildly from side to side. The pounding in Alice’s head seemed to echo the sound of the horses’ hooves. Surely one mouthful of brandy could not make her drunk, and yet the interior of the coach was now starting to spin in a manner that made her feel extremely sick. On the floor, tiny seed grains spun and danced, the same grains that had been on the dusty floor of the windmill, the same chaff that was clinging to Faye Cole’s cobwebbed skirts… Even as Alice registered surprise that the high-in-the-instep Duchess of Cole would venture abroad in dirty skirts, the significance of those grains of wheat hit her so violently that she gasped.

“It was you! You were in the windmill! You were the one who tried to push me down the stairs!”

“You have led something of a charmed life, have you not, Miss Lister?” Faye Cole said, baring her teeth in a smile that chilled. “Lord Vickery’s quick reflexes saved you that day on Fortune Row, and after that he would not let you from his sight. He even managed to spring you from jail when we were so sure that we had managed to have you locked up and out of the way. And today, on the stairs, you were almost within my grasp!” Her hand moved with the swiftness of a striking snake to whip a knife from beneath her skirts and level it at Alice’s throat. “Well, not anymore. Lord Vickery is not here and you are in our power now.”

Alice put out a hand to grab the duchess’s wrist, but even as she did the coach lurched again and her head whirled and she tumbled from the seat onto the floor. Henry Cole picked her up, his hands suddenly offensively intimate, his breath hot on her face.

“Opium,” the duchess uttered. “My dear Miss Lister, you are going to sleep now.”

Alice tried to wrench herself away, but she could not breathe, could barely think, and then the darkness came rushing in so quickly that it seemed all the stars went out.

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

LYDIA AWOKE SLOWLY. Her body felt pleasantly languid from Tom’s most recent lovemaking and she was as warm and contented as was possible, given that she was curled up under a smelly old horse blanket on a prickly mattress in an old barn on the Cole Court estate. It had been Lydia’s idea to take refuge at Cole because she knew every last inch of the estate, where to find food and where to hide. But time was passing and they were no closer to clearing Tom’s name. In the last few days, Tom had seemed more preoccupied, barely speaking to her about his plans, though his amorous attentions to her were as ardent as ever.

Lydia stretched, relishing the echo of pleasure that rippled through her body, and reached out a hand to her lover. He was not there.

She sat up abruptly, the shreds of sleep driven from her mind by a sudden fear. Where had Tom gone? Why had he not told her he was going out? Why had he left her? Was he safe? Lydia’s insecurities, barely hidden below the surface, rose and almost choked her. She scrambled up, tidying her clothes with trembling hands, grabbing her shoes, stumbling to the door.

The cold wind hit her in the face as soon as she went outside, and the rain soaked her. She scoured the dark moors desperately, giving a sigh of relief as she saw Tom’s figure walking down the track to the east, the road that led down to Cole Court itself. Even now, as a wanted man and with a price on his head, he had a jaunty walk, a cocksure manner that Lydia had always found so confident and appealing but that now, for some reason, struck a chill into her heart. He looked very purposeful. He was going somewhere-without her. She started to stumble after him; she called out, but the wind whipped the words from her mouth and carried them away and Tom did not turn.

Lydia started to hurry. Perhaps, she thought, Tom was going to Cole Court to ask her father’s permission to wed her. That was a nice idea. She had told Tom how her family had cast her out and disowned her, how she had lost her inheritance, and he had not seemed to care much. He had told her that he was sure they would take her back once his innocence was proven and their wedding had taken place. Noble families, Tom had said, hated scandal. Once she was finally and respectably married it would all be swept under the carpet and forgotten. Perhaps, Lydia thought, Tom was so eager to wed her that he was going to plead her case with her parents, proclaim his innocence and ask for their help in clearing his name so that the marriage could take place as soon as possible. The thought warmed her even as the rain drenched her clothes and made her shiver.

She had reached the edge of the deer park and was about fifty yards from the road when she saw the Cole carriage, driven at a breakneck pace, turn into the drive in a spatter of mud and rather than make its way toward the stable yard, veer off down a short track to where a small, squat, rounded building sat on its own. Lydia knew it was the icehouse. Tom, she noted, had also seen the carriage arrive and now he moved toward it, cutting between the trees of the deer park, still ahead of her and still not looking back. Lydia opened her mouth to call out to him again, but then closed it. She was not sure what it was that prompted her to keep quiet, but a strange and unpleasant unease was creeping through her limbs now and seemed to be weighting them with lead.

The Duke and Duchess of Cole were descending the carriage, and Lydia watched as Tom sauntered across the grass toward them. She saw her mother stiffen, a horrified expression crossing her face, and her father straighten up very tall and proud as though he were about to tell the coachman to horsewhip Tom from the estate. But Tom was speaking; she crept closer to hear what he was saying, pressing herself against the stout trunk of a concealing oak, her shaking fingers digging into the rough bark. Suddenly she did not want him to know that she was there. There was something terribly wrong. She knew it. She wanted to turn and run, but hideous curiosity held her planted to the spot.

“Cole!” Tom sounded disrespectful, she thought. “I’ve come to talk to you about your daughter.” He drove his hands into his pockets and strolled up to the duke and duchess. “I have Lydia,” he said. “She is my mistress. My pregnant mistress.” He gave Henry Cole an insolent look. “She must take after you, sir. She has an appetite for it.”

Lydia felt suddenly faint. She wanted to put her fingers in her ears and blank out what she was hearing, to run as fast as her legs could carry her. But it was too late. Her knees were trembling and she could not run anywhere and some hateful, horrible compulsion to know the worst held her still.

“What do you want, Fortune?” The duke sounded testy but not as angry as Lydia had thought he might. There was something else in his voice that struck an odd note, something that sounded like fear.

“I want money,” Tom said clearly. “I want you to make Lydia’s inheritance over to me and then I will marry her and leave the country-since there is a price on my head-and we’ll never trouble you again. You will be able to forget your harlot of a daughter. I’ll take her off your hands so that she won’t besmirch the Cole escutcheon anymore. But I’ll only do it if you pay me.”

“We don’t want anything to do with that little trollop!” The duchess’s voice rose to a screech and carried to Lydia on the wind. “Throwing herself away on you, and you barely even a gentleman. We’ll not pay you a penny. Be damned to you both.”

“Get out,” Henry Cole said. “You heard her.” He looked at his wife. “We don’t give a toss whether you marry the chit or not. Get out before we call the authorities to arrest you.”

Tom, Lydia thought, with a strange, cold detachment, was looking chagrined. If only he had asked me, she thought, with the same cold clarity. If only he had told me he was going to go to my parents and ask them to pay him to take me-and my scandalous name-away. I could have told him he was wasting his time by trying to extort the money from them. Because they do not care what happens to me. And neither does he…

Tom said something filthy and disgusting about throwing her in the gutter where she belonged with the other whores. Lydia covered her ears. The coachman really was going to horsewhip him now, and Tom knew he was beaten, turning away with one last lewd remark and walking off with as much dignity as he could muster. Lydia slumped against the unyielding trunk of the oak tree, the tears choking her throat, her heart pounding. She hated herself. She hated herself for being so stupid that she had trusted Tom not once, but twice, when he had never cared for her at all. Oh, he had lied and lied and told her he loved her and pretended he wished to wed her, but all the time he had been remembering that she had once been heiress to fifty thousand pounds and might be again. He was a gambler and she was his last bet…

He had lost. And so had she.

She straightened up. One day, she thought, I will tell Tom Fortune what I think of him. I will make him pay. But now she felt sick and ill and faint and all she wanted was the comfort of someone whom she knew loved her, which meant she must find her way to the village and seek out Alice or Lizzie or Laura and confess what a fool she had been again…

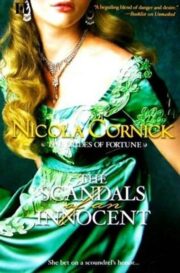

"The Scandals Of An Innocent" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Scandals Of An Innocent". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Scandals Of An Innocent" друзьям в соцсетях.