But her heart rate exploded. Terror swamped her.

‘Hello?’ she called out.

A guttural stream of Chinese came in response and a thump on the side of Box, the sound of a palm hitting metal. She shut up. The best thing was the light. She focused on the tawny little trickles of twilight that filtered through the six holes and steadied herself by it. It was only faint. A candle? An oil lamp? But it was light. Life. She could make out her own knees, see a bruise on her leg, see her hand. Her eyes squinted after the utter darkness they had grown accustomed to but they wanted more. More light. More life.

A scraping sound, something dragging across the floor. She sat still, listening. The squeak of metal, then a whoosh and suddenly water was coming through the holes. The shock was total. Quickly she pushed her face under it and opened her mouth. The joy of feeling moisture in her mouth took over and she gulped it down, greedy and stupid. Then the taste of it kicked in. It was foul. Rank with dirt. Full of grit. She retched on the floor. Her mouth was full of grease and acid bile. She rubbed at her tongue with her wrist.

The water kept coming. She forgot about her mouth.

‘Hey,’ she called out. ‘Stop it. Enough water.’

A man’s laugh and another bang on the side of Box.

‘Please. No more water. Qing. Please.’

The flow of water increased. It was inches deep already and her teeth were chattering so hard they hurt.

‘Stop!’ she shouted, but it came out as a wordless scream.

Focus.

Breathe.

Breathe deep. Fill your lungs.

The water rose. It crept up past her waist. She banged on the roof. ‘Please. Qing. Please.’

But the laughter grew louder. Gloating. Gleeful.

She’d got it all wrong. They were going to drown her. The noise of her blood in her ears was deafening. Why drown her? Why? It didn’t make sense.

As a lesson to Chang An Lo.

My love. My love.

The surface of the water rose to her chest, her neck, and she was ice cold. Her body felt paralysed. She forced it to move, squatted on her haunches, pushing her face up against the metal and kept dragging air deeper and deeper into her lungs. Abruptly rage ripped right through all her focusing and her breathing, and she hammered uncontrollably on the metal roof.

‘You let me out of here, you bloody murdering gutter scum, you filthy bastard son of the devil. I don’t want to die, I don’t, I…’

The water reached her mouth. She dragged in a last gulp of air. Held her breath. Closed her eyes. Water packed inside her nose, solid as snow. Spasms began in her calves and travelled up her body. In her mind she found Chang An Lo’s smile waiting for her and she kissed his warm lips.

Box filled to the brim.

Chang crouched in the garden. Close to the shed. Somehow it brought her nearer. Dawn was not yet anything more than a slight bleed in the sky behind him, but already a thrush was chattering its alarm call from high in a bare willow tree. A fanqui cat, a colourless shadow in the darkness, strolled round the edges of the frosted lawn staking out its territory, its thick fur ruffled by the wind from the northern hills.

The shed.

Chang had been inside, seen the blood, put a hand in the empty hutch. He promised Chu Jung, god of fire and vengeance, a lifetime of prayers and gifts in exchange for it being rabbit’s blood. Not Lydia’s.

Not Lydia’s.

He had worked all night, seeking out those with eyes that see. Twice he’d used the knife because twice he’d been seized by hands that took Po Chu’s silver. Fever had made his reactions slow but not that slow. The spiralling strike of his heel smashing a kidney, a tiger paw punch to the throat, a knife in the ribs to make sure. But before either of them went to join the spirits of their ancestors, Chang asked questions. Where was Po Chu now? His headquarters? His hideouts?

One gave answers and Chang followed the trail, but it led him into a black alley where only death lingered. Po Chu was being careful. It seemed he moved around, never long in one place, flitting at night, as alert as a bat to any threat. Chang couldn’t get close.

‘Po Chu, I swear by the gods that I will hound you down and make you eat your own blood-soaked entrails if you harm one hair of my fox girl.’

He howled it. In the darkened streets of the old town where guarded eyes watched from hidden doorways but few dared show a face. There was the stench of blood on him and on his blade, and they could smell it.

Chang waited for dawn to arrive. His own blood felt like lead in his veins because he knew he had become a death bringer. It followed him, padded silently at his heels, its foul breath cold on his neck, first to Tan Wah and now to Lydia. He knew she was going to die. Even if Po Chu wanted to recapture him and was using her as bait, still that devil son of Feng Tu Hong would delight in killing her. He would slit her throat when he was finished, to punish Chang for the loss of face. If for one second he believed that Po Chu would release her in exchange for himself, he would be there on his knees, his knife tossed to the ground. But no. Po Chu would kill them both. After his amusements with them.

Chang seized a handful of brittle icy grass from the lawn and pulled it out, stuffed it into his mouth to still the scream of pain that gripped his chest. To love someone. It sliced open your heart. It made it soft and pulsating when the crows came to tear it apart with their savage beaks. He dropped his face into his hands. The bandages had been discarded. Love made you vulnerable as a kitten asleep on its back, its tender belly exposed to the world. That’s how he felt. That weak. How could he fight when all he wanted to do was to protect her? Not China. Just her.

He bit on the raw place on his hand where his finger had once been and felt the pain of it dig into his mind, but still he could-n’t shake free from the hook that held him. He reminded himself of Mao Tse-tung’s doctrine that the needs of the Individual must be suppressed in support of the Whole. In his head he knew it to be the only way forward, but right now his head was as much use as a donkey in a gambling den.

His was a strong arm in the Communist fight and a strong mind.

She was one girl. A fanqui girl.

But there was one last way he might find her. Save her. Though he would certainly die. Would that be too selfish? To give his life for the girl he loved, instead of the country he loved.

Lydia, tell them what they want to hear. Don’t bare your teeth at them.

He spat out the grass. Rose to his feet and loped into the grey light of morning.

56

They did the water trick twice more. Each time for longer. Her lungs burned. She retched up filth. Snatched at air. Vision blurred. She wanted to die, yet each time she fought for life like a wild animal.

The man with the gloating laugh enjoyed his work. He kept slapping Box’s sides and chattering in high-pitched Chinese. Only when she knew that this time she would drown for certain, when stars flared in the black tunnel that filled her head and her lungs were seared by fire, did he dart around and slide a narrow slat from under her. The water gushed out and she curled very nearly dead on the floor of Box. Everything hurt.

When her bowels opened, she barely noticed.

She lost track of time.

Sometimes she pinched her cheek to make sure she was still alive. Still Lydia Ivanova.

She was beginning to doubt it.

When the bolt drew back again, her whole body flinched. The footsteps on the stairs. She forced her lungs to drag in air, deep down, expanding even the tiny sacs at the end of each airway. She had to stockpile on air. Before the water came. Her skin felt numb with cold. With panic. She crouched. Ready.

But this time there was no sound of dragging hosepipe. This time it was the scrape of something wooden across the floor and the flickering light grew brighter.

What now?

Focus. Breathe. Don’t cry.

Suddenly the world changed. The roof flew off. A hand reached in and grabbed her hair, wrenching it from its roots, hauling her to her feet. Her stiff body was sluggish and earned her a blow on the ear. She was staring into the face of an olive-skinned Chinese man with a pointed face and black eyes set close together. His teeth were red and for one crazy moment she thought it was blood, that he was eating some live creature, then she saw he was chewing on some dark red seeds that he held in his free hand.

‘Guo lai! Gi nu.’

He yanked her out of Box and she looked around her, eyes screwed up against the dim light. She was right. It was a cellar. Two rats paused in a corner and inspected her, whiskers twitching. Box was a metal cube raised on a wooden plinth with a drain underneath and a small ladder propped against its side. She fell down the ladder, her feet too numb to guide her.

Don’t cry. Don’t beg.

Spit in his goddamn face.

She didn’t cry. She didn’t beg. She didn’t spit in his face. She did as she was told. Her captor slipped wooden shackles on her wrists and a rope around her neck, then led her like a dog out of the cellar along a narrow dank corridor, slatted walls on both sides like some kind of passage between buildings. Up steps. Five of them. Should she try to break free? Here?

But it took everything inside her just to walk upright. When she stumbled or hesitated the rope was tugged tight with such force, she was under no illusion about the man’s strength and knew her own body was a physical wreck. So. No. No escape yet. The narrow-faced man pushed open a door.

Warmth.

That was what hit her first. It flowed over her skin, silky golden waves of it, sucking out the cold from her bones. She wanted to weep with pleasure. She felt a sudden rush of gratitude toward her captors for giving her this warmth, but part of her mind insisted that was insane. She hated them. Hated.

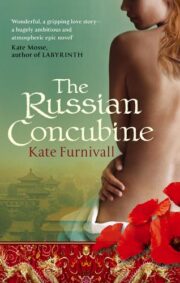

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.