‘Then I’ll earn it.’

He sighed and glanced out the window again as if seeking escape. At the next table two women in feathered hats laughed shrilly when a waitress brought them buttered crumpets, and Parker began polishing his spectacles yet again. Lydia realised it was a sign of stress.

‘How,’ he asked unhappily, ‘could you possibly earn it?’

‘I could help out at the newspaper. I can fetch and carry and make tea and…’

‘No.’

‘But…’

‘No. We have plenty of people to do all those things already and anyway, your mother would be furious with me if I distracted you from your educational studies.’

‘I’ll talk to her. I can get her to…’

‘No. That’s final.’

They stared at each other. Neither willing to look away.

‘There’s another way,’ Lydia said. ‘For me to earn two hundred dollars.’

Something in the way she said it made him instantly wary. He sat back in his chair and folded his arms across his chest, so that his jacket sleeves puckered and crumpled.

‘Let’s leave it there. Why don’t we just finish our cakes and talk about…,’ he searched for a subject, ‘… Christmas or the wedding.’ He gave her an encouraging smile. ‘Agreed?’

She returned his smile and withdrew her hand. ‘Certainly. The wedding is set for January, isn’t it?’

He nodded and his eyes grew bright at the thought. ‘Yes, and I hope you’re looking forward to it as much as your mother and I are.’

She picked up a sugar cube from the bowl and started to suck one corner of it. Parker didn’t look pleased, but he passed no comment.

‘It seems to me,’ she said gently, ‘that the start of a marriage is an important time. You have to learn about each other, don’t you, and get used to living together. Accept the other person’s little habits and, well, foibles.’

‘There’s some truth in that,’ he said carefully.

‘So it seems to me,’ she took a tiny bite out of the sugar and crunched it between her teeth, ‘that having a ready-made daughter around could make the situation twice as… hard.’

He sat up straight, both hands flat on the table. His expression was stern. ‘What are you implying here, Lydia?’

‘Just that it would be extremely helpful to you if that daughter promised to do exactly as you told her. No arguments. No disobedience for, shall we say, the first three months of your new and, I’m sure, wonderful, married life?’

He closed his eyes. She could see his jaw clicking and unclicking. When he opened his eyes again they did not look as happy as she’d hoped.

‘That is extortion, young lady.’

‘No. It’s a bargain.’

‘And if I don’t agree to this bargain?’

She shrugged and bit another piece off the cube.

‘Are you threatening me, Lydia?’

‘No. No, of course I’m not.’ She leaned forward and the words tumbled out. ‘All I’m doing is asking you to give me a chance, a fair chance to earn two hundred dollars. That’s all.’

He shook his head, and the sugar tasted like ash in her mouth.

‘You are a devious child, Lydia Ivanova, but this kind of unholy behaviour must cease once your mother and I are married and you become Lydia Parker. I know your poor mother would be appalled at your duplicity.’ Suddenly he rapped the table hard three times with his silver cake fork. ‘Three months. With not a word or a look out of place from you. I have your word on it?’

‘Yes.’

He opened his wallet.

In a dimly lit yard marked out with a circle of straw bales, the dog that looked like a wolf was having its throat torn out. Inch by inch. Strips of fur and flesh flew across the circle. Gobbets of blood spewed out into the eager faces of the men who edged too close, as the pale dog, the one that looked like a ghost, shook its snarling head from side to side and dragged more of the soft gullet into its jaws. One ear was hanging by a thread. Its shoulder was ripped open and dangling down in a loose scarlet flap, but its grip on the wolf-dog’s throat was a death grip and the crowd roared its approval.

Lydia took one look at the savagery taking place inside the circle of straw, one glance at the bloodlust in the eyes of the men, and then she walked over to the wall and was quietly sick. She wiped her mouth. She’d come this far and now was not the time to back out. For five days she had scoured the Russian Quarter of Junchow, walked its mean streets after school each day, seeking out Liev Popkov. The bear man. The one with the eye patch and the boots. Five days of rain and wind.

‘Vi nye znayetye gdye ya mogu naitee Liev Popkov?’ she asked again and again. ‘Do you know where I can find a man called Liev Popkov?’

They had looked at her with suspicion and narrowed northern eyes. Anyone asking questions meant trouble. ‘Nyet,’ they shrugged. ‘No.’

Until tonight. She had plucked up the courage to walk into one of the dark and dingy bars, a kabak, that stank of black tobacco and unwashed male bodies. Hers was the only female face, but she stood her ground and finally on payment of a half dollar a toothless old goat told her to try the dog yard behind the stable.

Dog yard. More like death yard.

It was where the men gathered on a Friday night to get their thrills, raw and unadulterated. Dog fighting. It put fire in their bellies and in their veins, wiping out the degradation of a week of hard, miserable labour. Here they bet on who would live and who would die, knowing that a win meant a good night’s vodka and maybe a girl as well if their luck held.

Liev Popkov was there. Lydia spotted him easily. Towering above the tight huddle of onlookers whose breath drifted in the icy air like incense around the dark yard. A lantern on the wall behind Popkov threw his broad shadow across the circle and onto the warring dogs. She couldn’t see his face clearly but his great body looked motionless and lazy, and when he did shift position it was like the slow lumbering movement of a bear.

She went over and touched his arm.

His head turned, faster than she expected. Though one eye was obscured by the patch and the lower half of his face was covered by the black beard, his single eye registered complete surprise and his mouth fell open, revealing big strong teeth. Tombstone teeth.

‘Dobriy vecher. Good evening, Liev Popkov,’ Lydia said in her carefully rehearsed Russian. ‘I want to talk to you.’

She had to shout above the roar of the crowd and for a moment she wasn’t sure if he’d heard her or even understood her, because all he did was blink silently and continue to stare at her with his one dark eye.

‘Seichas,’ she urged. ‘Now.’

He glanced over at the dogs. An artery had been severed and canine blood pumped into the icy night air. His expression gave nothing away, so she had no idea if he was winning or losing, but he effortlessly shouldered a path through the press of men around him to the back wall of the yard. It was in deep shadow and smelled of damp.

‘You speak our language,’ he growled.

‘Not well,’ she replied in Russian.

He leaned against the wall, waiting for more from her, and she had a sudden image of it crumbling under his weight. Up close he was even bigger. She had to tilt her head back to look at him. At first that was all she saw. The bigness of him. That was exactly what she wanted. He was wearing a Cossack hat of moth-eaten fur jammed over his black curls and a long padded overcoat that stank of grease and came right down to the tip of his boots. And he was chewing something. Tobacco? Dog meat? She had no idea.

‘I need your help.’ The Russian words came to her tongue more readily than she expected.

‘Pochemu?’ Why?

‘Because I am searching for someone.’

He spat whatever was in his mouth onto the yard floor. ‘You are the dyevochka who made trouble for me. With police.’ He spoke gruffly but slowly. She wasn’t sure if this was his normal way or done just for her to understand the language that was still a struggle to her. ‘Why should I help you? You of all people.’

She opened her hand. In it lay Alfred’s two hundred Chinese dollars.

30

He didn’t speak, Liev Popkov. But neither did she. Yet they kept close, even touching at times. Side by side they hunched forward against the biting wind that whipped up off the Peiho River, and Lydia’s lungs ached with the effort.

‘Here,’ he muttered.

He meant the narrow street that twisted away from the quayside to their left. It was grey and cobbled and stank of putrid fish guts. She nodded. His broad shovel of a hand pulled her tight against him, so that not a crack of the thin wintry light sneaked between them and her body became no more than an extension of this great greasy bear. It was weird the effect he had on her mind. She felt big and bold and fearless. The hostile eyes around them no longer sent shivers down her spine, and when one of the Chinese dockhands reached out to touch her as he passed, Liev casually raised an arm and smashed his elbow into the man’s face. Broken bone and blood and high-pitched screams. She looked at the mess and felt ill. They kept on walking, no comment. Liev was a man of few words.

In the beginning on their first few forays down around the dock-land quays, she had tried to speak to him in her halting Russian, to offer some flow of simple conversation, but all she received in reply were grunts. Or no response at all. She grew used to it. It made it easier for her to concentrate on the faces that swarmed over the congested harbour and in the slippery hutongs, easier to avoid the thousands of shoulder poles carrying weighty piles of God-knows-what in their buckets and panniers. Easier to watch where her feet were stepping.

Easier. But not easy. None of this was easy.

‘Lydia Ivanova.’

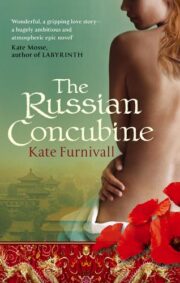

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.