‘Ah.’ The Englishman nodded silently, ran a hand thoughtfully over his forehead, and turned to Feng. ‘I’ll buy her from you.’ He said it casually, as he would for a bag of chestnuts from a street trader. He pulled a drawstring pouch from his pocket. It looked heavy. ‘Tonight’s share. For the chit.’ He tossed it across to Feng, but the Chinese made no attempt to catch it and it fell with a dull thump on the carpet at his feet.

‘The girl is not for sale,’ Feng said and stepped over the pouch. ‘She is to die. As an example to others who lie to us.’ His black eyes were fixed on the knife blade at his son’s throat. ‘But in exchange for that dung-stinking cur on his knees there, I offer you your own life, Chang An Lo. And my word of protection. You will need it. Or Po Chu will drain the lifeblood from your body as slowly and painfully as a boar roasts on a spit over a fire. Do you accept?’

There was a long silence. Outside a dog’s howl split the darkness.

‘I accept.’ Chang withdrew the knife.

Instantly a guard leaped forward and sliced the thongs that bound Po Chu. He struggled to his feet, his body stiff and shaking with shame. The faeces slithered down his legs. He looked ready to sink his teeth into Chang.

‘Po Chu,’ Feng snarled. ‘I have given my word.’

Po Chu did not move. He remained only inches from Chang, breathing hatred into his face.

Chang shut him out. His usefulness was over. His father would have let him die rather than swallow his own words. But Chang could not have asked for the girl’s life in payment for Yuesheng’s body because it would have dishonoured Yuesheng’s spirit. To be bargained for a fanqui. That brought shame. But the printing press was vital to China’s future and was something that Yuesheng had died for. It was a fitting price.

‘And the girl?’ the tall Englishman asked.

Feng looked over at him, saw his concern, and gave a small cruel smile. ‘Ah, you see, Tiyo Willbee, I have ordered her bowels to be twisted around her neck until she can no longer breathe and then her breasts to be cut off.’

The Englishman closed his eyes.

Chang doubted that it was true. Ordered her death, yes. But the manner in which she should die, no. The leader of the Black Snakes would leave such things to the inventiveness of his followers. He had spoken the words only to spit venom at his English guest. Chang wondered why.

‘Feng Tu Hong, I thank you for the honourable exchange we have made,’ Chang said with formal politeness. ‘A life for a life. Now I offer you something more important than a life.’

Feng had been striding toward the door, eager to rid himself of the sight and smell of his son. He halted.

‘What,’ he demanded, ‘is more important than life?’

‘Information. From General Chiang Kai-shek himself.’

‘Ai-aiee! For a toothless cub, you speak boldly.’

‘I speak truly. I have information of value to you.’

‘And I have men who know how to drag it from you with tortures you have never even dreamed of. So why should I bargain for it?’ He turned away.

The Englishman stepped forward. ‘Show some sense, Feng. Exacting information by such methods takes time.’ He gestured idly at Chang, leaving a trail of cigarette smoke in the air. ‘In this case, I suspect quite a lot of time. And maybe this is urgent. Where’s the harm in striking a deal?’ He laughed, soft and low. ‘After all, it’s what we did, you and I, and look where it’s got us.’

Feng frowned, impatience catching up with him. ‘So. What is this new bargain you offer?’

‘I will give you secret information. From Chiang Kai-shek’s office in Peking. In return you give me the flame-haired Russian.’

Feng laughed, a rich, strong sound that loosened his tight jaws and made the others in the room breathe easier. ‘You will have this chit? Whatever the cost?’

‘No. I will have her. For this cost.’

‘Very well. Agreed.’

‘Word has come from Chiang Kai-shek before he returns to his capital in Nanking. Elite troops are coming to Junchow. They are approaching as I speak. To destroy all Communists, spike their heads on the town’s walls, and dig out corruption in the government of Junchow. As honoured chairman of our Chinese Council, it seems to me this information is of value to you in advance of their arrival.’ He gave a low bow and heard Po Chu groan.

Feng remained still and silent for a long moment. His face had grown pale, in fierce contrast to his scarlet robe, and his broad hands clenched and unclenched. Suddenly he strode across the room.

‘The girl is yours,’ he called without turning. ‘Take her for yourself. But don’t expect any good to come of it. To mix barbarians with our civilised people is always a first step to death.’ A servant on his knees held open the door, and the leader of the Black Snakes was gone.

Chang gave the Englishman a nod. An acknowledgment of his help. Neither spoke. Po Chu spat on the floor with an incoherent curse, then disappeared into the night, so Chang left the room and made his way out into the courtyard once more. It was when he was crossing the shadows of the second courtyard that he saw a black uniformed guard trudging through the drizzle with drooping shoulders and a burden in each hand. In one was the severed head of the chow chow dog, its black tongue hanging out like a scorched snake. In the other was the head of the guard with the hungry face, his filmy eyes no longer alert. The price of failure in the household of Feng Tu Hong was high.

As Chang’s attention was distracted for a split second by this bloody sight, the full weight of a gun slammed into the side of his head and he slid into the blackness of hell.

27

September, and hot. Still hot.

A brass fan whirred on the ceiling. All it did was take bites out of the leaden air and chew it up a bit. Lydia was sick of standing here with her arms stretched out while Madame Camellia stuck pins in her. She was sick of the satisfied private smile on her mother’s face as she draped herself in the client’s chair and watched. Most of all she was sick of the silence from Chang. It roared in her ears and made her long for news of him.

No word for a month. A whole desperate month of not knowing.

He must have taken heed of her warning. Left Junchow. That had to be the reason for his silence. Had to be. Which meant he was at least safe. She clung to that thought, warmed her hands on it, and murmured again and again as she lay wide-eyed in bed at night, ‘He’s safe, he’s safe, he’s safe.’ If she said it often enough, she could make it true. Couldn’t she?

He was tucked away now in one of the Red Army training camps; she pictured him there, taking potshots at targets and marching up and down, polishing his boots and his buckles, doing scary things on the end of ropes. Isn’t that what soldiers did in camps? So he was safe. Surely. Please let him be safe. Please, let all his strange gods protect him. He was one of their own, wasn’t he? They’d care for him. But she took deep breaths to quiet her racing heart, because she didn’t trust them, neither his gods nor hers.

‘Darling, do stop fidgeting. How can Madame Camellia work properly when you won’t keep still?’

Lydia scowled at her mother. Valentina was looking extremely cool and elegant in an exquisite cream linen suit made by Madame Camellia, Junchow’s most coveted dressmaker. Her salon copied the very latest Paris fashions and had a long waiting list of clients, so it was an honour to be allowed to cut in line, all because of Alfred, who had pulled a few strings. Valentina’s heart was set on having the very best for her wedding.

‘Doesn’t she look adorable in it, Madame Camellia?’

The Chinese owner of the salon glanced up at Lydia’s face and studied it for a while in silence. Lydia was standing on a small round padded platform in the middle of the room while Madame Camellia touched and tugged and twitched the soft green silk, which was as pale as her songbird’s throat. A bird sat in a pavilion cage in the corner of the room and sang with a constant burst of trills and spiralling notes that grated on Lydia’s taut nerves.

‘She looks lovely,’ Madame Camellia said with a sweet smile. ‘The eau de nil colour with her hair is just perfect.’

‘You see, Lydia, I told you you’d adore it.’

Lydia said nothing. Stared at the jade pins in the dressmaker’s hair.

‘Mrs Ivanova, some swatches of the new tweeds from Tientsin arrived this morning. In readiness for winter. I thought you might like one for your honeymoon costume. Would you care to view them?’ It was spoken as if conferring a special privilege.

‘Yes, I’d be delighted.’

Madame Camellia nodded to her young assistant, and Valentina was escorted out of the room. The walls were pale and soothing with rose-pink drapes, but splashes of colour were provided by a bowl of orchids and the bird’s golden cage.

‘Miss Lydia.’ She spoke softly. ‘Would you like to tell me what it is about the dress that displeases you?’

The dress? As if she cared about the dress. She dragged her thoughts back into the room and looked down at the satin-smooth hair that was coiled up on top of the dressmaker’s head. A delicate camellia, made of the finest white silk, nestled in its ebony folds. She looked like a little black-crested bird, bright and quick, her tiny figure encased in a tight turquoise cheongsam with a side slit to show off one slender leg, but Valentina had mentioned that at night Madame dressed in stylish Western fashions while she did the rounds of the nightclubs on the arm of her latest American lover. She had made herself into a wealthy woman and could pick and choose.

She looked at Lydia with intelligent eyes.

‘Tell me how you’d like it to be.’

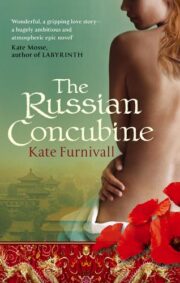

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.