She rose and stood in the doorway of the French windows, staring out into the blackness. Nothing moved. Not even a bat or a branch. She could see no one, but that didn’t mean they could-n’t see her. Nevertheless she stepped out on the terrace and started to dance, a Chopin waltz floating softly through the open windows. The damp air felt cool on her cheeks and her bare arms shivered with secret pleasure as she spun and swayed on her own to the music. For one inward moment everything else was washed away, leaving her head clear and clean at last.

‘How quaint.’

She stopped and swung around. A young man in his early twenties was leaning languorously against the door frame, observing her. Slowly and deliberately he started to applaud. It was almost an insult.

‘Enchanting.’

‘It is impolite to spy on a person,’ Lydia said sharply.

He shrugged indifferently. ‘I had no idea this terrace was reserved for just you.’

‘You should have made your presence known.’

‘The dancing display was too… entertaining.’ He spoke English with a slight Russian accent and his mouth curled up at one side.

‘General Manlikov’s entertainment is provided in the ballroom, not out here. A gentleman would respect a lady’s privacy.’ It was meant to be cutting, the way Valentina sometimes spoke to Antoine.

He drew a silver cigar case from his breast pocket, took his time lighting a cheroot, first tapping its end on the back of the case, and then regarded her with a lazy mocking expression. He clicked his heels together and tipped his head in a curt bow.

‘I apologise for not being a gentleman, Miss Ivanova.’

The fact that he knew her name came as a shock. ‘Have we met?’ she demanded.

But as the words came out of her mouth, she realised who she was talking to. It was Alexei Serov, the son of Countess Natalia Serova. She barely recognised him now. Except for his manner. That was as haughty as ever. But his thick brown hair had been cropped very short and he was wearing an elegant white evening jacket with finely tapered black trousers that emphasised his long limbs. He looked every inch the son of a Russian count.

‘I seem to remember we were introduced in a restaurant. La Licorne, I do believe.’

‘I don’t recall,’ she said in an offhand manner and moved away from him to lean against the stone balustrade that edged the terrace. ‘I’m surprised you do.’

‘As if I could forget that dress.’

‘I like this dress.’

‘Clearly.’

The music ceased and suddenly the night air was full of silence. She made no effort to break it. Faintly she could smell wood smoke mingling with the aroma of his tobacco. It struck her as a very male smell. It made her think of Chang. Not that he smelled of smoke; no, his was more of a clean river smell, or was it of the sea? For a brief second she wondered if his skin would taste salty on her tongue, and instantly felt herself blush, which irritated her.

‘You’re the Russian girl who doesn’t know how to speak Russian, aren’t you?’ said Alexei Serov.

‘And you’re the Russian who doesn’t know how to speak English politely.’

Their eyes fixed on each other and she became aware that his were green and very intense, despite the air of casual indifference he assumed.

‘The music was excellent,’ he commented.

‘Rather average, I thought. The bass was too heavy and the tempo uneven.’

His mouth curved again in that arrogant way of his. ‘I bow to your superior knowledge.’

She felt the urge to demonstrate that she knew more of the world than just music. ‘It is peaceful here now in the International Settlement for pleasant soirées like this.’ She gestured toward the brightly lit room. ‘But everything in China is changing.’

‘Do enlighten me, Miss Ivanova.’

‘The Communists are demanding equality for workers instead of feudalism, and a fair distribution of land.’

‘Forget the Communists.’ He said it dismissively. ‘They will be stamped out within the next few weeks. Right here in Junchow.’

‘No, you’re wrong. They’re…’

‘They are finished. General Chiang Kai-shek has ordered an elite division of his Kuomintang troops to be sent here to rid us of their flea bites. So you are quite safe with your soirées, don’t worry.’

‘I’m not worried.’

But she was.

Suddenly a quickstep struck up in the ballroom, a surge of music full of life and energy.

On impulse Lydia said, ‘Would you like to dance?’

‘With you?’

‘Yes.’

‘Out here?’

‘Yes.’

His face looked as if she’d just asked him to jump into the honey wagon. ‘I think not. You are too young.’

She was stung. ‘Or is it that you are too old?’ she retorted and started to dance on her own again as if oblivious to his presence.

Round and round in dizzying circles, but it annoyed her that Alexei Serov didn’t have the courtesy to leave. She kept her eyes half closed and would not look at him, blanking him out and letting Chang take her into his arms instead, as she floated on the faint breeze and her body swayed and twirled from one end of the terrace to the other. The rhythm of the music seemed to beat inside her blood. Her breath came fast and she could feel her skin so alive it seemed to be aware of every touch of the night dew and each shiver of a moth’s wings as it fluttered toward the circle of light.

‘Ya tebya iskala, Alexei.’

Lydia stopped, her mind still spinning. A young woman was standing beside Alexei Serov, holding a glass of red wine in each hand and speaking words Lydia could not understand. Her straight blond hair was shaped into a neat corn-coloured cap and she wore a modern dress that stopped just below the knee like Lydia’s own, but this young woman’s was beaded all over in vivid blues, a Paris dress, a fashion-house dress. It emphasised the blue of her eyes, which right now were focused with surprise on Lydia. The moment was over. Lydia treated the pair to what was meant to be a gracious nod of the head and walked past them with chin high. They were murmuring to each other in Russian but as Lydia re-entered the ballroom, she heard Alexei Serov slip deliberately into English.

‘That girl is just like her father. He had a temper too. I once saw him throw his violin on the fire because he could not get the note he wanted from it.’

Lydia’s ears were burning. But she kept walking.

Chang An Lo watched her. From the damp darkness of a sprawling weeping willow tree. Watched her on the terrace the way he would a long-tailed swallow, swooping and diving through the sky for the pure joy of it. The air around her seemed to vibrate and her hair set the night on fire. He could feel its heat and hear the crackle of its flames.

He breathed lightly and felt a sharp unmistakable flicker of anger rise up in him. The dance and the music were strange to his senses, but Lydia Ivanova’s actions were clear. She was moving the way a young female cat moves in front of a likely male when she’s ready to mate, swaying and seductive, seeking out his advances, rubbing and purring and twitching her flanks.

The man was acting uninterested, his body soft and boneless in the strip of yellow light from the window, but he didn’t leave. His eyes hooked into the dancing girl in such a way that it made Chang want to skewer him on the tip of a fishing spear and watch him writhe. It was not only the Black Snakes that slithered toward her. The boneless man’s hands forgot to smoke the cheroot between his fingers, but his half-closed eyes did not forget to watch each graceful dip and rise of her hips. He stayed there.

Like the shadow stayed. The one by the steps up to the terrace, the one merging with the bulk of a water butt, deeper black against black. The one whose breath would end. A gleam from a window glinted on the metal of a shuriken in a poised hand.

Chang drew his knife. He watched over her.

25

‘Mama, is it true my father played the violin?’

‘Where did you hear that?’

‘At the soirée. Is it true?’

‘Yes, it’s true.’

‘Why did you never tell me?’

‘Because he played it so badly.’

‘Did he once throw a violin into a fire in anger?’

Valentina laughed softly to herself. ‘Ah yes, more than once.’

‘So he had a temper?’

‘Da. Yes.’

‘Am I like him?’

Valentina turned back to painting her nails. Her glossy new bob swung over her cheek, hiding her expression from Lydia’s sharp gaze. ‘Every time I look at you, I see his face.’

‘Get out of bed.’

‘No.’

‘Darling, you drive me crazy. You’ve been lying in bed all week.’

‘So?’

‘I don’t understand you. Usually you’re in such a rush to be out and doing things but now… Oh dochenka, you make me spit, you really do. Just because the school term is finished and you’ve got yourself a mountain of books there, it doesn’t mean you can read the rest of your life away.’

‘Why not? I like reading.’

‘Don’t be so wretched. What is that big fat book anyway?’

‘War and Peace.’

‘Oh gospodi! For God’s sake, make it Shakespeare or Dickens or even that imperialist pig Kipling, but please not Tolstoy. Not Russian.’

‘I like Russian.’

‘Don’t be silly, you know nothing Russian.’

‘Exactly. Time I did, don’t you think?’

‘No, I do not. It’s time you got out of bed and went over to Polly’s to eat some of her lily-white mother’s plum pie that you always sing the praises of. Go out. Do something.’

‘No.’

‘Yes.’

‘No.’

‘You must.’

‘Why do you want me out of here? Because you want to jump into bed with Antoine?’

‘Lydia!’

‘Or is it Alfred now?’

‘Lydia, you are a rude and impertinent child. I just want you to be normal, that’s all.’

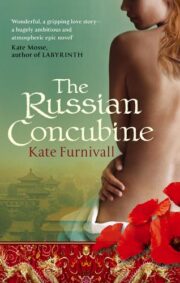

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.