‘Danger from the Black Snake brotherhood.’

He hissed, a hard and angry sound. ‘Thank you for the warning. They threaten me, I know. But how do you hear of the Black Snakes?’

She gave him a lopsided smile. ‘I had a chat with two men who had black snake tattoos on their necks. They dragged me into a car and demanded to know where you were.’

She made light of it, but his heartbeat trailed away to nothing. He dipped his hand into the water to hide the sudden tremble. He must rule the anger, not let it rule him. His dark eyes looked into hers.

‘Lydia Ivanova, listen to me. You must stay out of the Chinese town. Never go near it, and be watchful even in your own settlement. The Black Snakes carry poison in their bite and they are powerful. They kill slowly and savagely, and…’

‘It’s all right. They let me go. Don’t look so fierce.’

She was smiling at him, and his heartbeat returned. She dragged a hand through her hair as if plucking thoughts from her head, and he could feel in the tips of his fingers her desire to talk of other things.

‘Where do you live, Chang An Lo?’

He shook his head. ‘It’s better you do not know.’

‘Oh.’

‘It is safer for you. To know nothing of me.’

‘Not even what job you do?’

‘No.’

She released a little huff of annoyance, puffing out her cheeks as a lizard will sometimes do, then tilted her head and gave him an enticing grin.

‘Will you at least tell me your age? That can do no harm, can it?’

‘No, of course not. I am nineteen.’

Her questions were rude, far too personal, but he knew she did not mean them to be and he took no offence. It was her way. She was a fanqui and to expect subtlety in a Foreign Devil was like expecting toads to bring forth the song of a lark.

‘And your family? Do you have brothers and sisters?’

‘My family is dead. All dead.’

‘Oh, Chang, I’m sorry.’

He took his hands from the water and drew a bullfrog from the mud. ‘Are you hungry, Lydia Ivanova?’

He lit a fire. He baked the frog and also two small fish from the river, all wrapped in leaves, and she ate her share in front of him with relish. He whittled four sticks into rudimentary chopsticks and enjoyed teaching her to use them, touching her fingers, curling them around the sticks. Her laughter when she dropped the fish from them made the branches of the willow trees whisper above their heads and even Lo-shen, the river goddess, must have stopped to listen.

She relaxed, in a way he’d never seen before. Her limbs grew loose; her eyes emerged from their shadows and abandoned that wary look that was as much a part of her as her flaming hair. And he knew what it meant: she felt safe. Safe enough to tell him a tale of when she was eight years old and broke her arm trying to imitate one of the backflips of the street acrobats. A Chinese girl had tied two bamboo chopsticks tight on each side of the break to keep it safe until she reached home. Her mother scolded her but as soon as it was well again, she had arranged for a Russian ballet dancer to teach her daughter the correct way to do a backflip. To demonstrate, Lydia Ivanova jumped to her feet, leaped into the air, and performed a neat flip that sent her skirt flying over her head for a moment in a most undecorous manner. She sat down again and grinned at him. He loved her grin.

He laughed and applauded her. ‘You are Empress of Lizard Creek,’ he said and bowed his head low.

‘I didn’t think Communists approved of empresses,’ she said with a smile and stretched out on her back on the sand, her bare feet trailing in the cool water.

He thought she was teasing him but he was not sure, so he said nothing, just watched her where she lay in the shade, the tip of her tongue between her lips as if tasting the fresh breeze that flickered off the water. Her body was slight and her breasts small, but her feet were too big for Chinese taste. She was so unlike any other he’d ever known. So alien, so fiery, a creature that broke all the rules, yet she brought a strange warmth to his chest that made it hard for him to leave her.

‘I must go,’ he said softly.

She rolled her head to face him. ‘Must you?’

‘Yes. I am to go to a funeral.’

Her amber eyes grew wide. ‘Can I come too?’

‘That is not possible,’ he said curtly.

Her audacity would test the patience of the gods themselves.

They stood at the back of the procession. Trumpets blared out. He could feel the fox girl behind him, sense her excitement as she clung close. She was small and slight like a Chinese youth, and the clothes he’d borrowed for her – white tunic, loose trousers, felt sandals, and wide straw conical hat – made her invisible. But her presence here worried Chang.

Would Yuesheng object? Would the appearance of a fanqui at his funeral give power to the evil spirits that the drums and cymbals and trumpets were driving away? Oh, Yuesheng, my friend, I am indeed bedevilled.

Even the sky was white, the colour of mourning, displaying its grief for Yuesheng. The coffin carriage at the head of the solemn procession was draped in swathes of white silk and drawn by four men all in white, declaring their sorrow. Buddhist priests in saffron robes beat their drums and scattered white petals along the winding route to the temple. Chang felt the girl’s cheek brush his shoulder as the crowd crushed around them.

‘The man in the long white gown and ma-gua,’ he murmured, ‘the one prostrate on the ground behind the coffin, he is Yuesheng’s brother.’

‘Who is the big man in the…?’

‘Hsst! Do not speak. Keep your head down.’ He looked over his shoulder but could see no one paying any attention to them. ‘The big man is Yuesheng’s father.’

The chanting of the priests drowned out their words.

‘What are those people throwing in the air?’

‘It is artificial paper money. To appease the spirits.’

‘Shame it’s not real,’ she whispered as a fifty-dollar note floated past her nose.

‘Hsst!’

She did not speak again. It was good to know the fox could hold its tongue. During the slow progress to the temple, Chang filled his mind with his memories of Yuesheng and the bond they had shared. It had always weighed heavy on Chang’s heart that Yuesheng had not seen or spoken to his father for three years because of the anger he carried against him. Three long years. The ancestors would be displeased that he had hardened his face against his duty of filial respect, but Yuesheng’s father was not a man easy to honour.

In the temple, in front of the bronze statues of Buddha and Kuan Yin, the coffin was placed at the altar. Incense scented the air. Prayers were chanted by monks. White banners, white flowers, delicate food, fruit and sweetmeats, all laid out for Yuesheng. The mourners kowtowed to the ground like a blanket of snow on the temple floor. Then the burning began. In a large bronze urn the monks laced their prayers with the smoke of burned paper objects for Yuesheng to use in the next life: a house, tools and furniture, a sword and rifle, even a car and a set of mah-jongg tiles, and most important of all, foil ingots of gold and silver. Everything devoured by the flames.

Chang watched as the smoke rose to become the breath of the gods, and he felt the beginning of a sense of peace. The knife pain of loss grew less. Yuesheng had died bravely. Now his friend was safe and well cared for, his part in the work was over, but as Chang’s eyes sought out the heavy figure at the front of the mourners, he knew his own work had barely begun.

‘You are the one who brought me my son’s body, and for that I owe you a great debt. Ask what you will.’

The father wore a white headband. His white embroidered padded jacket and trousers made his shoulders and thighs look even broader than they were. The sash at his thick waist was decorated with pearls sewn into the shape of a dragon.

Chang bowed. ‘It was an honour to serve my friend.’

The big man studied him. His mouth was hard and his eyes shrewd. Chang could see no grief in them, but this man did not reveal his emotions lightly.

‘They would have cut off his limbs and scattered them, if you had not carried his body away to me. The Kuomintang does that to frighten others. It could have taken my son’s spirit many years to find them all before returning whole to our ancestors. For that gift, I thank you.’ He bowed his head to Chang.

‘My heart is happy for your son. His spirit will be pleased to know you offer a gift in return.’

The black eyes tightened. ‘Name the gift and it shall be yours.’ Chang took a deliberate step closer and kept his voice low. ‘Your son gave his life for what he believed in, to open the minds of the people of China to the words of Mao Tse…’

‘Do not speak to me of that.’ The father turned his head away in a dismissive gesture, the muscle at the top of his jaw bunched and hard. ‘Just name the gift.’

‘A printing press.’

A harsh intake of breath.

‘Your son’s press was destroyed by the Kuomintang.’

‘My word is given. The printing machine shall be yours.’

Chang bowed, no more than a dip of his head. ‘You do great honour to your son’s memory, Feng Tu Hong.’

Yuesheng’s father turned his broad back on Chang and strode away to the funeral banquet.

He must take the fox home. She had seen enough. If she stayed, she would be discovered. The guests were no longer bowing their heads in grief but were tipping them back to drink maotai, chattering like pigeons. She would be noticed. He glanced over his shoulder to where she was tucked close behind him and wondered what would happen if he lifted off her wide straw hat. Would the fire spirits of her hair sweep through the great crowd of guests and burn the truth from their tongues: that they had offered no kindness to Yuesheng while he lived?

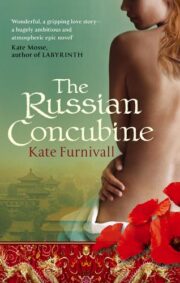

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.