‘There will be no patrol tonight. I have it on good authority.’

‘May your tongue not lie, Englishman. Or neither of us will be alive to watch the sky grow pale.’ He drank another beaker of rotgut, rose heavily from his stump of a seat, and went out on deck in silence.

Except there was no silence here. The vessel creaked and flexed and groaned softly at every touch of a wave as it made good progress downriver. Theo could smell the salt water of the Gulf of Chihli and feel its clean breath sweeping away the stench of rotting fish and kerosene that filled the rattan hut in which he was sitting. The hut had a low curved roof, and the woven material was infested with insects that dropped at intervals into his hair or into the dish of fried prawns. He spied a fat millipede crawling on his shirt, picked it off with disgust, and dropped it in his host’s beaker.

‘You eat more?’ It was the master’s woman. She was small and timid, her eyes never rising to his.

‘Thank you, but no. The sea turns my stomach into a mewling brat that cannot keep down good food. Maybe later, when this is over.’

She nodded but didn’t leave. Theo wondered why. She stood there, plump and greasy in a shapeless tunic, her black hair pulled back from her face and twined up into a loose coil, and she stared in silence at the cat. Theo waited, but no more words came from her. He tried to think what she might want. Food? Unlikely. She cooked fish and rice in a cauldron under another rattan shelter at the stern where, by the look of her, she fed herself well. She would never sit down to eat with the men because the act of eating was regarded by Chinese as ugly in a woman, so it was something she did in private, like pissing in a pot.

No, this was not about food.

‘What is it?’ he asked gently. He saw her swallow hard as if she had a fish bone in her throat. ‘Are you fearful that the guns will come tonight? Because I have promised that they will not attack us while we…’

She was shaking her head and her stubby fingers were twisting the amber beads round her neck into a tight knot. ‘No. Only the gods know what will be tonight.’

‘Then what is troubling you?’

A shout sounded on deck and feet raced past the hut. Quickly she turned to Theo. For the first time her small black eyes flicked up to his and he was shocked by the distress in them.

‘It’s Yeewai,’ she said. ‘It’s not safe for her here among these men. They are brutal. Please take her to the International Settlement where she will be safe. Please, I beg you, master.’ She came so close to him he could smell the grease in her hair and held out a fist to him. When she opened it, four gold sovereigns lay on her palm. ‘Take this. To care for her. Please. It is all I have.’

She glanced nervously in the direction of the opening to the hut, frightened her man would return, and Theo’s eyes followed hers. He was expecting to see a young girl-child standing there, and already he was shaking his head in refusal.

‘Please.’ She took his hand and thrust the gold into it, then turned and seized the cat. She crushed the animal’s battered old face against her own and Theo heard a brief harsh sound issue from the creature’s mouth that he assumed was meant to be a purr, before she threw it into a bamboo box and twisted a length of twine around to hold down the lid. She thrust the box into Theo’s arms.

‘Thank you, master,’ she said in a choked voice, tears flowing down her cheeks.

‘No,’ Theo said and started to push it back at her, but she was gone. He was alone in the hut with a bad-tempered creature called Yeewai. ‘Oh, Christ! Not now. I don’t need this now.’ He placed the bamboo box down on the planks next to the rope and gave it a kick. A growl like the sound of a blast furnace shot back at him and a claw raked his shoe.

The wind blew stronger now and the deck swayed alarmingly under his feet, so that he felt the need to hold on to the wooden rail but would not allow himself that luxury. Beside him the master of the junk stood as solid and steady as one of the rocks that threatened to tear a hole in them if they dared to venture too close to shore. They were watching the mouth of the river, the waves etched in silver as the moon picked out a two-masted schooner with a long dark prow. It had tacked smoothly out of the bay and was gliding up toward them, its white sails spread wide like the wings of a black-necked crane against the night sky.

‘Now,’ Theo muttered under his breath. ‘Now you shall measure the weight of my word.’

‘My life is on your word, Englishman,’ the Chinese skipper snarled.

‘And my life depends on your seamanship.’

The wind carried away his response. Suddenly the crew were readying a small craft to slide into the river, and fifty yards off Theo could see men on the schooner doing the same. Dark figures spoke in urgent whispers, and then the two scows pulled fast through the water toward each other until their port sides rubbed together like dogs greeting one another and a crate passed over their bows. It took no more than ten minutes for the boats to be back aboard the mother vessels and the crate to be hauled away from thieving hands into the rattan hut.

Theo could not bring himself to look at it, so he stayed on deck, but he could hear the junk master slapping his broad thighs and laughing like a hyena. Theo stood in the bows as they skimmed back upriver and was tempted to light a cigarette but thought better of it. Now that they were carrying the contraband they were in real danger, and a glowing cigarette end might be all it took. He was aware that the oil lamp in the hut had been extinguished and they were travelling across the water like a dark shadow, with only the moon’s cold glare to betray them. He stuck a Turkish cheroot in his mouth and left it there, unlit.

He was trusting Mason. And deep in his heart he knew that was a mistake. If that bastard hadn’t done his part, then the skipper was right. Neither of them would see the dawn. Damn him. With an uneasy growl he sucked on the cheroot, tasted its bitter dregs, and then tossed it down into the waves. Self-interest was Mason’s bible. On that Theo had to rely.

But every breath of the way, he prayed for clouds.

The patrol boat came from nowhere. Out of the night. Its engine roared into life and raced at them out of a narrow inlet, pinning the junk in its powerful searchlight and circling it with a fierce surge of bow wave. The junk rocked perilously. Two men leaped overboard. Theo didn’t see them but he heard the splash. In a moment’s madness it occurred to him to do the same, but already it was too late. A rifle in the patrol boat was fired into the air as a warning and the customs officers in their dark uniforms looked ready to back it up with more.

Theo ducked into the hut and before his eyes grew accustomed to the deeper level of darkness, he felt a knife at his back. No words were said. They were not necessary. To hell with Mason and his sworn oath. ‘No patrols tonight, old boy. You’ll be safe, I swear it. They want you there on the boat.’

‘As a hostage to their own safety, I assume.’

Mason had laughed as if Theo had made a joke. ‘Can you blame them?’

No, Theo couldn’t blame them.

A match was struck and the kerosene lamp hissed into life, drenching the air with the stink of it. To Theo’s surprise it was the junk master at the lamp. The knife was in the hand of the woman. Her man was growling something so rough and coarse that Theo couldn’t understand, but he had no need to. The long curved blade in the skipper’s right hand was not there to open the crate at his feet.

‘Sha!’ he shouted to the woman. Kill.

‘The cat,’ Theo said quickly over his shoulder. ‘Yeewai. I’ll take her.’

The woman hesitated for only the beat of a wing but it was enough. Theo had his revolver out of his pocket and pointing straight at the junk master’s heart.

‘Put down the knives. Both of you.’

The skipper froze for a moment, and Theo could see the black eyes calculating the distance across the hut to the Englishman’s throat. That was when he knew he would have to fire. One of them would die right now and it wasn’t going to be him.

‘Master, come quick.’ It was one of the deckhands. ‘Master, come see. The river spirits have driven away the patrol boat.’

It was true. The sound of the engine was fading, the fierce searchlight gone. Blackness seeped back into the hut. Theo lowered the gun and the junk master instantly leaped out on deck.

‘They were bluffing,’ Theo muttered. ‘The patrol boat officers just wanted to let us know.’

‘Know what?’ the woman whispered.

‘That they are aware of what we’re doing.’

‘Is that good?’

‘Good or bad, it makes no difference. Tonight we win.’

She smiled. Her front teeth were missing but for the first time she looked happy.

The shack on the riverbank was foul and airless, but Theo barely noticed. The night was almost over. He was off the water and would soon be in his own bath with Li Mei’s sweet fingers washing the sweat off his back. Relief thundered into his brain and suddenly made him want to kick Feng Tu Hong in the balls. Instead he bowed.

‘It went well?’ Feng asked.

‘Like clockwork.’

‘So the moon did not steal your blood tonight.’

‘As you see, I am here. Your ship and crew are safe to run another night, another collection.’ He rested a foot on the crate that stood between them on the floor, as if it were his to give or take away at whim. It was an illusion. They both knew that. Outside, a cart stood ready.

‘Your government mandarin is indeed a great man,’ Feng bowed courteously.

‘So great that he talks to the gods themselves,’ Theo said and held out his hand.

Feng let his lips spread in what was meant to be a smile, and from a leather satchel on his hip he drew two pouches. He handed them to Theo. Both clinked with coins, but one was heavier than the other.

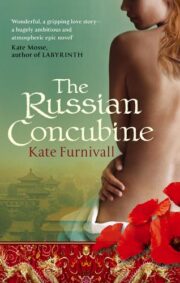

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.