‘He is wrong. Your journalist must be deaf and blind.’

‘And he says the foreigners are China’s only hope for the future if this country is to come out of the Dark Ages and modernise.’

Chang dropped her hand. A surge of anger at the arrogance of the Foreign Devils rose in his throat and he cursed them for their greed and for their ignorance and for their vengeful god who would devour all others. Her golden eyes stared at him in confusion. She didn’t understand and would never understand. What was he doing? He stepped back quickly, leaving her Mr Parker’s lies in her lap, but his fingers did not listen to his head and felt as empty as a river without fish.

‘Did he not tell you, Lydia Ivanova, that the foreigners are cutting off China’s limbs? They demand reparation payments for past rebellions. They cripple our economy and strip us naked.’

‘No.’

‘Nor that the foreigners rub China’s bleeding face in the pig dung by their rule of extraterritorial rights in the cities they stole from us? With these rights the fanqui ignores the laws of China and makes up his own to please himself.’

‘No.’

‘Nor that he wrapped his fist around our customs office and controls our imports. His warships swarm in our seas and our rivers like wasps in a crate of mangoes.’

‘No, Chang An Lo. No, he did not.’ For the first time she seemed to gather fire into her words. ‘But this he did say, that until the people of China break free from their addiction to opium, they will never be anything but a weak feudal nation, always subservient to some kind of overlord’s whim.’

Chang laughed, loud and harsh, the sound raking across the broken walls.

She said nothing, just stared at him, shadows stealing her face from his eyes. Some night creature flitted silently over their heads, but neither looked up.

‘That’s something else your Parker forgot to tell you.’ His voice was so low she had to lean forward to hear, and again he breathed in the scent of her damp hair.

‘What?’

‘That it was the British who first brought opium to China.’

‘I don’t believe you.’

‘It’s true. Ask your journalist man. They brought it in their ships from India. Traded the black paste for our silks and our teas and spices. They brought death to China, not only with their guns. As surely as they brought their God to trample on ours.’

‘I didn’t know.’

‘There is much you don’t know.’ He heard the sorrow in his own voice.

In the long silence that followed, he knew he should leave. This girl was not good for him. She would twist his thoughts with a fanqui’s cunning and bring him dishonour. Yet how could he walk away without tearing the stitching from his soul?

‘Tell me, Chang An Lo,’ she said just as the headlamps of a car swept into their brick shell, revealing the tight grip of her fingers on a coin she must have picked up from the floor, ‘tell me what I don’t know.’

So he knelt down in front of her and started to talk.

That night Yuesheng came to Chang in a dream. The bullet that had smashed through his ribs and torn into his heart was no longer there, but the open hole remained and his face was well fed in the way Chang remembered from before the bad times.

‘Greetings, brother of my heart,’ Yuesheng said through lips that didn’t move. He was dressed in a fine gown with a round embroidered cap on his head and a hooded hunting hawk on his arm.

‘You do me great honour to come to me before your bones are even in the earth. I mourn the loss of my friend and pray you are at peace now.’

‘Yes, I walk with my ancestors in fields thick with corn.’

‘That pleases me.’

‘But my tongue is sour with acid words and I cannot eat or drink till I have emptied them from my mouth.’

‘I wish to hear the words.’

‘Your ears will burn.’

‘Let them burn.’

‘You are Chinese, Chang An Lo. You come from the great and ancient city of Peking. Do not dishonour the spirit of your parents and bring shame on your venerable family name. She is fanqui. She is evil. Each fanqui brings death and sorrow to our people and yet she is bewitching your eyes. You must see clear and straight in this time of danger. Death is coming. It must be hers, not yours.’

Suddenly, with a wet gushing sound, the hole in Yuesheng’s body was filled with boiling black blood that smelled like burned brick, and a high-pitched noise issued from him. It was the sound of a weasel screaming.

18

Theo stood on the bank and swore. The river lay flat as if it had just been ironed and the moonlight stretched long fingers over its surface, ruining all his hopes. The boat wouldn’t come. Not on a night like this.

It was one o’clock in the morning and he had been waiting among the reeds for more than an hour. The earlier rain and heavy clouds had provided the perfect cover, a black soulless night with only the solitary light of an occasional flimsy fishing sampan burning holes in the darkness. But no boat came. Not then. Not now. His eyes were tired of peering into nothingness. He tried to distract himself with thoughts about what was taking place just a mile upriver in Junchow’s harbour. Coastal patrol boats cruised in and out throughout the night, and once he heard the crack of gunfire. It gave him a quick pump of adrenaline.

He was hidden under the drooping boughs of a weeping willow that trailed its leaves in the water among the reeds, and he worried that he was too invisible. What if they couldn’t find him? Damn it, life was always choked with what ifs.

What if he’d said no? No to Mason. No to Feng Tu Hong. What if…?

‘Master come?’

The faint whisper made him jump, but he didn’t hesitate. He accepted the offered hand from the tiny wizened man in the rowboat and climbed in. It was a risk, but Theo was too deeply in to turn back now. In silence, except for the faintest sigh of oars through water, they travelled farther downriver, hugging the bank and seeking out the shadows of the trees. He wasn’t sure what distance they rowed or how long it took, for every now and again the little Chinese river-jack shot the boat deep into the reeds and hung in there until whatever danger it was that startled him had passed.

Theo didn’t speak. Noise carried over water in the still night air and he had no wish for a sudden bullet in the brain, so he sat immobile, one hand on each side of the rickety craft, and waited. With the moonlight camped possessively on the centre of the river, he didn’t see how they could possibly make the planned rendezvous, but this was the first run and he didn’t want it to go wrong. He could taste the anticipation like a shot of brandy in his stomach and however much he tried to feel disgusted, he couldn’t manage it. Too much rested on tonight. He trailed one hand in the water to cool his impatience.

And suddenly it loomed right there in front of him, the curved sweep of a large junk with the long pole to steer at the stern and black sails half furled. It lay in deep shadow in the mouth of an unexpected creek, invisible until you could reach out and touch it. Theo tossed a coin to the Chinese river-jack and leaped aboard.

‘Look, Englishman.’ The master of the junk spoke Mandarin but with a strange guttural accent Theo could barely understand. ‘Watch.’

He grinned at Theo, a wide predatory grin with sharp pointed teeth, then scooped up two fried prawns on the tip of his dagger, flicked them up into the air in a high arc, and caught them both in the cavern that was his mouth.

He offered Theo the knife. ‘Now you.’

The man was wearing a padded jacket, as if the night were cold, and stank like a water buffalo. Theo separated out two good fat prawns from the pile in the wooden dish in front of him, balanced them on the blade of the knife, and tossed them into the air. One fell neatly into his mouth, but the second hit his cheek and skidded onto the floor. Instantly a grey shape darted out from a coil of rope, devoured the prawn, and slunk back to its rope bed. It was a cat. Theo stared. It was a rare sight these days. He assumed it must live permanently on the boat because if it set foot on dry land, it would be skinned and eaten before its paws were even dirty.

His host roared with laughter, unpleasant and insulting, then slammed a fist on the low table between them and emptied the contents of his horn beaker down his throat. Theo did the same. It was an evil-tasting liquid that had the bite of a snake, but he felt it squeeze the life out of his nerves, so he downed a second beaker and grinned back at the junk master.

‘I will ask Feng Tu Hong for your worthless ears on a plate as payment for tonight’s work if you do not show me respect,’ he said in Mandarin and watched the man’s narrow eyes grow dull with fear.

Theo stuck the knife point into the table and left it swaying there. A hooded oil lamp that was slung from a hook just above their heads sent the crucifix shadow of the dagger sliding into Theo’s lap. He reminded himself he didn’t believe in omens.

‘How long before we meet up with the ship?’ he asked.

‘Soon.’

‘When does the tide turn?’

‘Soon.’

Theo shrugged. ‘The moon is high now. The river’s secrets are there for all to view.’

‘So, Englishman, that means tonight we will learn whether your word is worth its weight in silver taels.’

‘And if it’s not?’

The man leaned forward and plucked out the knife. ‘If your word is worth no more than a hutong whore’s promises, then this blade will make a journey of its own.’ He laughed again, his breath ripe in Theo’s face. ‘From here,’ he jabbed the blade toward Theo’s left ear, ‘to there.’ It came to rest under Theo’s right ear.

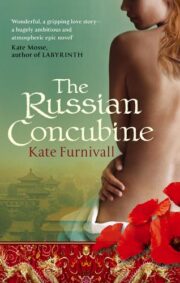

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.