For a moment there was no answer, then a long sigh filled the silence. ‘You know precisely what I’m talking about, Christopher.’

‘Good God, woman, I’m not a damned mind reader.’

‘The American woman. Tonight at the party. Is that the way you’d like Polly to behave?’

‘For Christ’s sake, is that what this is all about and the reason you made me come home early? Don’t be so absurd, Anthea. She was just being friendly and so was I, that’s all. Her husband is a business contact of mine and if only you would be a bit more outgoing, a bit more fun at these…’

‘I saw you both being friendly on the terrace.’

It was said quietly. But the slap that followed it echoed around the hall, and Anthea’s sharp gasp of pain drew Lydia from her hiding place. She stepped forward into the kitchen doorway, but the couple in the hall were too intent on each other to notice her. Mason was hunched forward like a bull, his neck sunk into the shoulders of his rumpled dinner jacket, one arm outstretched and ready to swing again. His wife was leaning back, away from him, one hand to her cheek where a red mark was flaring outward to her ear. The earring was missing.

Her blue eyes were huge and round, just like Polly’s, but full of such despair that Lydia could hold back no longer. She darted forward but too late. Another slap sent Anthea Mason spinning around. She staggered, caught herself on the umbrella stand, and ran into the drawing room, slamming the door after her. Mason stormed into the dining room, where Lydia knew the brandy was kept, and kicked the door shut behind him. Lydia stood there in the middle of the hall, shaking with fury. From inside the drawing room she could hear the muffled sound of crying and she longed to rush in there, but she had enough sense to know she would not be welcome. So she walked back up the stairs, indifferent to how much noise she made, and returned to Polly’s room.

One glance at her friend’s face and Lydia knew Polly had heard enough of what had gone on downstairs. More than enough. Her mouth was pulled so tight it was almost bloodless, and she wouldn’t look at Lydia. She was sitting on the edge of her bed, a doll clutched fiercely against her chest, her breath coming in quick little puffs. Lydia went over, sat down beside her and took one of Polly’s hands in her own. She held it tight. Polly leaned against her and said nothing.

17

Chang was still there when the fox girl came back into the burned-out house. He’d waited for her alone in the darkness, knowing she’d return before she knew it herself. The rain had stopped and a thin sliver of moon shimmered on the wet bricks around him and caught the edge of one of the coins she had discarded so readily. He knew how much money meant to her, but he also knew it would not be the money that drew her back. As soon as she stepped over the threshold, he could see she no longer carried her anger with her or wanted to drive a sword through his heart. He thanked the gods for that. But her limbs seemed to weigh heavy on her and the line of her shoulders was curved down like a camel’s back. It pained him to see it.

She stood by the empty doorway, letting her eyes adjust. ‘Chang An Lo,’ she called out. ‘I can’t see you but I know you are here.’

How did she know? Could she sense his presence as keenly as he sensed hers? He moved away from the wall and into the moonlight.

‘I am honoured by your return, Lydia Ivanova.’ He gave a deep bow to show her that he wanted no more harsh words between them.

‘Why a Communist?’ she asked and slumped down onto a block of concrete that had once been part of a chimney. ‘What makes you crazy enough to want to be a Communist?’

‘Because I believe in equality.’

‘That makes it sound so simple.’

‘It is simple. It is only men with their greed who make it complicated. ’

She gave a strange snort of scorn that took him by surprise. No Chinese woman would ever make such a noise in front of a man.

‘Nothing is ever that simple,’ she said.

‘It can be.’

The mandarins in her Western world had crowded her mind with untruths and blinded her eyes with the mist of deceit, so that she was seeing what they told her to see instead of what was in front of her. Her tongue was quick, but it tasted only the salt of lies. She knew nothing of China, nothing that was true. He moved around to squat down beside the wall again, the bricks solid at his back, and leaned forward to see her face more clearly. He had never known her so still or heard her voice so empty.

‘Do you know,’ he asked in a gentle tone not meant to anger her, ‘that women and children are still sold as slaves? That absent landlords rob the peasants of the food on their tables and the crops in their fields? That villages are stripped of men, seized by the army, leaving the weak and the old to starve in the streets? Do you know these things?’

She looked at him, but her face gave nothing away tonight.

‘China is not going to change,’ she said. ‘It’s too big and too old. I’ve learned at school how emperors have ruled as gods for thousands of years. You can’t…’

‘We can.’ He felt the heat rising in his chest when he thought of what must yet be done. He wanted her to know it. ‘We can make people free, free to think, free to work for an equal wage. Free to own land. The workers of China are treated worse than pigs. They are stamped into the dung like beetles. But the rich eat from gold plates and study in the scrolls of Confucius how to be a Virtuous Man.’ He spat on the ground. ‘Let the Virtuous Man try a day on his hands and knees in the fields. See which matters more to him then, a perfect word in one of Po Chu-i’s poems or a bowl of rice in his belly.’ He picked up a piece of broken brick at his side and crushed it against the wall. ‘Let him eat his poem.’

‘But Chang An Lo, you have eaten poems.’ She spoke quietly, but he could hear the impatience under her words. ‘You are an educated person and know it is the only way forward. You said yourself you came from a wealthy family with tutors and…’

‘That was before my eyes were opened. I saw my family riding on the broken backs of slaves and I was ashamed. Education must be for all. For women as well as men. Not just the rich. It opens the mind to the future, as well as the past.’

He thought of Kuan with her degree in law, so fierce in her determination to open the minds of the workers that she was prepared to work sixteen hours a day on a filthy factory floor where ten employees died each week from machine accidents and exhaustion. This fox girl knew nothing of any of this. She was one of the privileged greedy fanqui who had taken great bites out of his country with their warships and their well-oiled rifles. What was he doing with her? To ask her to change the patterns of her mind would be like asking a tiger to give up its stripes.

He stood up. He would leave her to her scattered coins and her thieving ways. One day she would be caught, one day she would grow careless, however closely he guarded her steps.

‘You’re going?’

‘Yes.’ He bowed to her, low and respectful, and felt something split in his chest.

‘Don’t go.’

He shut his ears and turned his back on her.

‘Then say good-bye to me.’ Her voice seemed to grow emptier, as if she knew he would not return this time, and a small noise escaped from her throat. She held out her hand as the foreigners did.

He walked over to where she sat on the concrete, bent down to take her small hand in his, and as his face came closer to hers, he smelled the rain on her hair. He breathed it in and inhaled it deep into his lungs until the scent of her seemed to fill his mind, the way the river mists fill the night sky. Her hand lay in his and he could not make his fingers release it. The moon stepped back behind a cloud, so that her face was hidden from him but her skin felt warm against his own.

‘And the foreigners?’ Her voice was barely a whisper in the darkness. ‘Tell me, Chang An Lo, what do the Communists aim to do to the fanqui?’

‘Death to the fanqui,’ he said, but he did not wish for her death any more than he wished for his own.

‘Then I must put my faith in Chiang Kai-shek,’ she said.

She was smiling; he could hear it in her voice though he could not see it with his eyes, but he did not want her to say such words, not even in jest. He felt a fleck of anger land on his tongue like ash.

‘The Communists will one day win, Lydia Ivanova, I warn you of that. You Westerners do not see that Chiang Kai-shek is an old tyrant under a new name.’ He spat again to the ground as the devil’s name passed his lips. ‘He has a lust for nothing but power. He proclaimed that he will lead our country to freedom, but he lies. And the Kuomintang Central Committee is a dog that jumps when he cracks the whip. He will destroy China. He strangles at birth all signs of change, yet the foreigners feed him with dollars to make him grow wise, the way an emperor feeds his pet tiger with songbirds to make him sing.’

His hand was gripping her fingers too hard and he could feel her bones fighting each other, but she gave no sign.

‘It will never happen,’ he finished.

‘But the Communists are cold killers,’ she said without withdrawing her hand. ‘They cut out their enemies’ tongues and pour kerosene down their throats. They bring China’s new industries to a halt with their strikes and sabotage. That’s what Mr Parker told me tonight. So why did you give them my necklace money?’

‘For guns. Your Mr Parker is twisting the tail of truth.’

‘No, he’s a journalist.’ She shook her head and he felt a trickle of spray from her wet hair. It flicked on his cheek and set his skin alive. ‘He must know what’s going on, that’s his job,’ she insisted. ‘And he believes Chiang Kai-shek will be the saviour of China.’

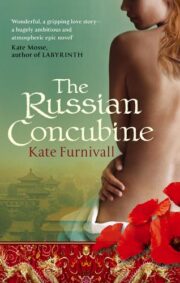

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.