‘Hush, Lydia, don’t be a silly. I love dancing.’

‘You can’t bear men with two left feet. You say it’s like being trampled by a moose.’

‘I shall be protected from that fate this evening because Mr Parker has kindly offered to accompany me and make sure I do not sit like a wallflower on my first night.’

‘No chance of that,’ Parker put in gallantly.

‘Do you dance well, Mr Parker?’ Lydia asked.

‘Passably.’

‘Well, then you are in luck, Mama.’

Her mother gave her a look that was hard to read, then left on Parker’s arm. When they reached the lower landing, Lydia heard Valentina exclaim, ‘Oh dear, I have forgotten something. Would you be an angel and just wait downstairs for me? I won’t be a moment.’ The sound of her footsteps running back up the stairs. The door opened, then slammed shut.

‘You stupid, stupid little fool.’ Valentina’s hand swung out. The slap made Lydia’s head whip back. ‘You could be lying in a police cell right this minute. Among rats and rapists. Don’t you leave this house,’ she hissed, ‘not till I come back.’

And she was gone.

In all her life her mother had never raised a hand to her. Never. The shock of it was still ricocheting through Lydia’s body, making it jump and tremble. She put a hand to her stinging cheek and let out a low guttural moan. She roamed around the room, seeking relief in movement, as if she could outpace her thoughts, and then she spotted the package in the Churston Department Store tissue paper that Parker had left behind in his eagerness to escort her mother. She picked it up, opened it, and found a silver cigarette case inlaid with lapis lazuli and jade.

She started to laugh. The laugh wouldn’t stop; it just kept ripping its way up from her lungs over and over until she was suffocating on her own sense of the absurd. First the necklace and now the cigarette case, both in her grasp but both beyond her reach. Just as Chang An Lo was now. Chang, where are you, what are you doing? Everything she wanted had slipped from her grasp.

When the laughter finally ceased, she felt so empty, she started stuffing biscuits into her mouth, one, then another and another until all the biscuits were gone. Except one. She crushed up the last one, mixed it with the grass and leaves in her paper bag, and went down to Sun Yat-sen.

14

The wall was high and lime-washed, the gate built of black oak and carved with the spirit of Men-shen. To guard against evil. A lion prowled on each gatepost. Theo Willoughby stared into their eyes of stone and felt nothing but hatred for them. When an oil-black crow settled on the head of one, he wanted its talons to tear out the lion’s stone heart. The way his own hands wanted to tear out the heart of Feng Tu Hong.

He summoned the gatekeeper.

‘Mr Willoughby to see Feng Tu Hong.’ He chose not to speak in Mandarin.

The gatekeeper, in grey tunic and straw shoes, bowed low. ‘Feng Tu Hong expect you,’ he said.

The keeper’s wife led Theo through the courtyards. Her pace was pitiful, her feet no longer than a man’s thumb, bound and rebound until they stank of putrefaction under their bandages. Like this hellish country, rotten and secretive. Theo’s eyes were blind to China’s beauty today despite the fact that he was surrounded by it. Each courtyard he passed through brought new delights to caress the senses, cool fountains that soothed the heat from the blood, wind chimes that sang to the soul, statues and strutting peacocks to charm the eye, and everywhere in the dusky evening light stood ghost-white lilies to remind the visitor of his own mortality. In case he should be rash enough to forget it.

‘You devil-sucking gutter-whore!’ The words sliced through the darkness.

Theo halted abruptly. Off to his right in an ornate pavilion, lanterns in the shape of butterflies cast a soft glow over the dark heads of two young women. They were playing mah-jongg. Each one was gilded and groomed and dressed in fine silks, but one was cheating and the other was swearing like a deckhand. In China it is easy to be fooled.

‘You come,’ his guide murmured.

Theo followed. The courtyards were intended to show wealth. The more courtyards, the more silver taels the owner could boast, and as Theo knew only too well, Feng Tu Hong was the kind of man who loved to boast. As he passed under an ornately carved archway strung with dragon lanterns and into the final and grandest courtyard, a figure stepped out of the shadows. He was a man of about thirty with too much of the fire of youth still in his eyes. His hand was on the knife at his belt.

‘I search you,’ he said bluntly.

He was broad and stocky with soft skin, and Theo recognised him immediately.

‘You will have to use that blade on me first, Po Chu.’ Theo spoke in Mandarin. ‘I have not come to be treated like a dog’s whelp. I am here to speak with your father.’

He stepped around the man in his path and marched toward the elegant low building that lay ahead of him, but before he came anywhere near its steps, a blade fashioned like a tiger’s claw was pressing between his shoulder blades.

‘I search,’ the voice said again, harsher this time.

Theo did not care for it. He had no intention of losing face, not here. He swung around so that the knife was now directly over his heart.

‘Kill me,’ he growled.

‘Gladly.’

‘Po Chu, put down that knife at once and beg forgiveness of our guest.’ It was Feng Tu Hong. His deep voice roared around the courtyard and stamped out the faint murmur of voices from the other courtyards.

The blade dropped. Po Chu fell to his knees and bowed his head to the ground.

‘A thousand pardons, my father. I meant only to keep you safe.’

‘It is my honour you must keep safe, you mindless mound of mule dung. Ask forgiveness of our guest.’

‘Honourable father, do not order this. I would tear out my bowels and watch the rats devour them, rather than ask it of this son of a devil.’

Feng took a step closer. Under his loose scarlet robe he had squat powerful legs that could kick a man to death and the shoulders of an ox. He towered over his son, whose forehead was still pressed tight to the tiled floor.

‘Ask,’ he commanded.

A long intake of breath. ‘A thousand pardons, Tiyo Willbee.’

Theo tipped his head in scornful acknowledgment. ‘Don’t make that mistake again, Po Chu, not if you want to live.’ He drew a short horn-handled knife from inside his sleeve and tossed it to the ground.

A hiss escaped from the hunched figure.

His father folded his arms across his broad chest with a grunt of satisfaction. In the swirling shadows of the cat-grey twilight Feng Tu Hong looked like Lei Kung, the great god of thunder, but instead of a bloody hammer in his massive hand, he carried a snake. It was small and black and had eyes as pale as death. It coiled around his wrist and tasted the air for prey.

‘I expected never to see you in this house again, Tiyo Willbee. Not while I live and have strength to slice open your throat.’

‘Neither did I expect to stand once more on this carpet.’ It was an exquisite cream silk floor covering from the finest hand weavers in Tientsin, a gift four years ago from Theo to Feng Tu Hong. ‘But the world changes, Feng. We never know what lies in store for us.’

‘My hatred of you does not change.’

Theo gave him a thin smile. ‘Nor mine of you. But let us put that aside. I am here to speak of business.’

‘What business can a schoolteacher know?’

‘A business that will fill your pockets and open up your heart.’

Feng uttered a snort of disdain. Both knew that when it came to business, he had no heart. ‘Just because you dress like a Chinese’ – he stabbed a thick finger toward Theo’s long maroon gown, felt waistcoat, and silk slippers – ‘and speak our language and study the words of Confucius, don’t imagine that it means you can think like a Chinese or do business like a Chinese. You cannot.’

‘I choose to dress in Chinese clothes for the simple reason that they are cooler in summer and warmer in winter, and they do not choke off the blood to my mind like a tie and collar. So my mind is as free to take the winding path as any Chinese. And I think like a Chinese enough to know that this business I bring to you today is sufficiently important to both of us to bridge the black seas that divide us.’

Feng laughed, a big sound that held no joy. ‘Well spoken, Englishman. But what makes you think I need your business?’ His black eyes flicked around the room and fixed back on Theo’s.

Theo took his meaning. The room could not have been more opulent if it had belonged to Emperor T’ai Tsu himself, but its crass gaudiness grated on Theo’s love of Chinese perfection of line. Everything here was gold and carved and inlaid with precious jewels; even the songbirds in their gilded cage wore pearl collars and drank out of Ming bowls encrusted with emeralds. The chair Theo was sitting in was gold-leafed, with dragons of jade for armrests and diamonds as big as his thumbnail for each eye.

This room was Feng Tu Hong’s boast to the world, as well as his warning. For on each side of the doorway stood two reminders of what he had come from. One was a suit of armour. It was made of thousands of overlapping metal and leather scales, like the skin of a lizard, and its gauntlet grasped a sharpened spear that could rip your heart out. On the other side stood a bear. It was a black Asian bear with a white slash on its chest, rearing up on its hind legs, its jaws gaping to tear your throat to shreds. It was dead. Stuffed and posed. But a reminder nonetheless.

Theo nodded his understanding. At that moment a young girl, no more than twelve or thirteen, came into the room carrying a silver tray.

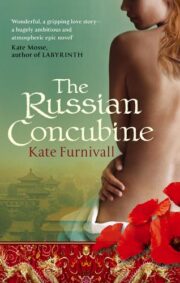

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.