‘Let us pray,’ Parker said and rested his head on his hands, bowing forward against the back of the bench in front.

Lydia did the same.

‘Lord,’ Parker murmured, ‘pardon us all, sinners that we are. Especially forgive this young girl her transgression and bring her the peace that passeth understanding. Dear Lord, guide her with thy Almighty hand, by the grace of Jesus Christ our Saviour, Amen.’

Lydia watched between her fingers as a wood louse crawled toward Parker’s shiny brogue shoe. There was a long silence and she considered making a run for it now that he’d released her hand. But she didn’t. He’d be quick to seize hold of her the moment she moved a muscle from the absurd prayer position, and anyway, she liked it here. The emptiness and the silence. When she closed her eyes she felt as if she were floating up in it. Looking down. Waving good-bye to the rats and the hunger below. Is this what angels feel like? Weightless and carefree and…

She snapped open her eyes. So who on earth would look after her mother and Sun Yat-sen if she drifted away on a fluffy white cloud? God didn’t seem to have done much of a job with the millions of Chinese starving to death out there, so why should she think He would bother with Valentina and a scrawny white rabbit?

She let the silence settle around her again, eyes only half closed.

‘Mr Parker.’

‘Yes?’

‘May I say a prayer too?’

‘Of course. That’s what we’re here for.’

She took a deep breath. ‘Please, Lord, forgive me. Forgive my wicked sin, and make my Mama better from her illness, and while I’m in prison, please don’t let her die, like Papa did.’ She remembered something she had heard Mrs Yeoman say. ‘And bless all Your children in China.’

‘Amen to that.’

After a moment they sat up straight. Parker was looking at her with concern blunting the anger in his brown eyes and placed a hand on her shoulder. ‘Where is it that you live?’

‘What is your name?’

‘Lydia Ivanova.’

‘You say your mother is ill?’

‘Yes, she’s sick in bed. That’s why I had to come into town on my own and why I had to take your wallet, you see. To pay for medicine.’

‘Tell me truly, Lydia, have you ever stolen before?’

Lydia turned a shocked face to his as they rode into the Russian Quarter in a rickshaw. ‘No, Mr Parker, never. Cut my tongue out if I lie.’

He nodded at her with a slight smile, his head making her think of an owl. Round glasses, round face, and a small beak of a nose. But clearly nowhere near as wise as an owl. She was confident that once he’d seen her mother comatose on the bed and their dismal room looking like a bear pit, his heart would melt and he’d let her go. He’d forget about the blasted police and maybe even give her a few dollars for a meal. She sneaked a sideways glance at him. He did have a heart. Didn’t he?

‘Was the watch that was stolen from you very valuable?’ she asked as the rickshaw rattled into her street. It looked desperately shabby even to her eyes.

‘Yes, it was. But that’s not the point. It belonged to my father. He gave it to me before he left for India, where he was killed, and I’ve carried it with me ever since. The thought of it all those years in his waistcoat pocket and then in mine meant something special to me. Now it’s gone.’

Lydia looked away. To hell with him.

She flew up the two flights of stairs. She could hear Parker’s footsteps right behind her. That surprised her. He must be fitter than he looked. She pushed open the door to the attic, darted into the room…

And stopped.

She did not feel Parker bump into her but caught his gasp of surprise.

‘Mama,’ she said, ‘you’re… better.’

‘Darling, what on earth do you mean? There was never anything wrong with me. Nothing at all.’

Nothing at all. Valentina was standing in the middle of the room and despite the darkness of her hair and of her dress, she managed to make the place brighter. Her hair gleamed, soft and perfumed, around her shoulders and she was wearing a navy silk dress with a wide white collar, cut low to emphasize the curve of her breasts. It fitted snugly at her hips but was designed to hang loose elsewhere, cleverly hiding the lack of flesh on her bones. Lydia had never seen it before. She thought her mother looked wonderful. Shining and glossy.

But why now? Why did she have to choose this moment to transform into a bird of paradise? Why, why?

Parker coughed awkwardly.

‘And who is our visitor, Lydia? Aren’t you going to introduce us?’

‘This is Mr Parker, Mama. He wants to meet you.’

Valentina’s smile enveloped him and drew him into her world. She held out her hand, the movement elegant and inviting. He took it in his. ‘Charmed to make your acquaintance, Mr Parker.’ She laughed and it was just for him. ‘Please excuse our sad little abode.’

For the first time Lydia noticed the room. It had changed. It sparkled. Windows thrown open, every surface polished, each cushion in place. A room full of gold and bronze and amber lights, with no trace of a dead body on the floor or a discarded shoe under the table. The air smelled of lavender, and not an ashtray in sight.

This was not what Lydia had planned for him.

‘Mrs Ivanova, it’s a pleasure to meet you. But I’m afraid to say I am not here with good news.’

Valentina’s hands fluttered. ‘Mr Parker, you alarm me.’

‘I apologise for bringing you cause for concern, but your daughter is in trouble.’ Despite his words, his glance at Lydia was remarkably benign, and she began to feel on surer ground. Maybe he would pass over the wallet episode.

‘Lydia?’ Valentina shook her head indulgently, making her dark mane dance. ‘What has she been up to now? Not swimming in the river again.’

‘No. She stole my wallet.’

There was a long silence. Lydia waited for the explosion, but it didn’t come.

‘I apologise for my daughter’s behaviour. I will have words with her, I promise you.’ Valentina spoke in a low, tight voice.

‘She told me that you were ill. That she needed money for medicine.’

‘Do I look ill?’

‘Not at all.’

‘Then she lied.’

‘I’m considering going to the police.’

‘Please, don’t. Please allow her this one mistake. It won’t happen again.’ She swung around to face her daughter. ‘Will it, dochenka?’

‘No, Mama.’

‘Apologise to Mr Parker, Lydia.’

‘Don’t worry, she has already done so. And more importantly, she has asked God for forgiveness too.’

Valentina raised one eyebrow. ‘Has she indeed? I’m so glad to hear it. I know just how much she cares about the state of her young soul.’

Lydia’s cheeks were burning and she scowled at her mother. ‘Mr Parker,’ she said quietly, ‘I do apologise for lying to you, as well as stealing. It was wrong of me, but when I left here, my mother was…’

‘Lydia, darling, why not make Mr Parker a nice cup of tea?’

‘… my mother was out and I was very hungry. I didn’t think straight. I lied because I was frightened. I’m sorry.’

‘Nicely said. I accept your apology, Miss Ivanova. We will forget the matter.’

‘Mr Parker, you are the kindest man in all the world. Isn’t he, Lydia?’

Lydia tried not to laugh and went over to the corner to make tea. She had seen this before, the way a man left his brains on the doorstep the moment he set foot in a room that contained her mother. One flutter of her dark lustrous eyes was all it took. Men were such idiots. Couldn’t they see when they were being plucked and trussed? Or didn’t they care?

‘Come and sit down, Mr Parker,’ Valentina invited with a smooth shift of subject, ‘and tell me what brings you to this extraordinary country.’

He took a seat on the sofa and she placed herself beside him. Not too close, but close enough.

‘I’m a journalist,’ he said, ‘and journalists are always attracted to anything extraordinary.’ He gazed at Valentina and laughed selfconsciously.

Lydia watched him from her corner, the way his whole body was drawn toward her mother; even his spectacles seemed to lean forward. He might be a fool for a petticoat but he had a nice laugh. She listened idly to their chatter, but her thoughts were a jumble.

What exactly had happened here?

Why was her mother all done up in new finery? Where had it come from?

Antoine? It was possible. But it didn’t explain the shine on the room or the lavender in the air.

She placed the tea in their single remaining cup in front of Mr Parker and slipped him a smile. ‘I’m sorry we have no milk.’

He looked mildly taken aback.

‘You must drink it black,’ Valentina laughed, ‘like we Russians do. Much more exotic. You will like it.’

‘Or I could go out and buy some milk for you,’ Lydia offered. ‘But I would need some money.’

‘Lydia!’

But Parker studied Lydia. His gaze travelled over her washed-out dress and her patched sandals and her thin wrists. It was as if he’d only just realised that when she’d said poor, it meant having nothing. Not even milk. From his wallet he pulled two twenty-dollar notes and handed them to her.

‘Yes, go and buy some milk, please. And something to eat. For yourself.’

‘Thank you.’ She left before he changed his mind.

It took no more than ten minutes to get hold of milk and half a pound of Marie biscuits, but when she returned, Valentina and Parker were on their feet ready to leave. Valentina was pulling on a pair of new gloves.

‘Lydochka, if I don’t go now, I will be late for my new job.’

‘Job?’

‘Yes, I start today.’

‘What job?’

‘As a dance hostess.’

‘A dance hostess?’

‘That’s right. Don’t look so surprised.’

‘Where?’

‘At the Mayfair Hotel.’

‘But you’ve always said that dance hostesses were no better than…’

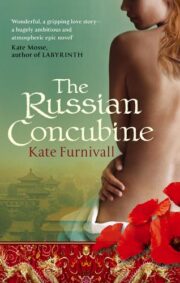

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.