‘I’m as all right as I’ll ever be.’

Lydia kissed her cheek and bundled the sleeping little rabbit into her arms as she slid from the bed.

‘Thank you, darling.’ Valentina’s eyes were closed, the shadows flickering over her face. ‘Thank you. Put out the candle on your way.’

Lydia drew a deep breath and blew out the light.

‘Lydia.’ The word hung in the darkness.

‘Yes?’

‘Don’t bring that vermin into my bed again.’

The next five days were hard. Everywhere Lydia went she could not stop herself from looking for Chang An Lo. Among a sea of Chinese faces, she constantly sought one with an alert way of holding his head and a livid bruise. Any movement at her shoulder made her head turn in expectation. A shout across the street or a shadow in a doorway was all it took. But at the end of five days of staring out of her classroom window in search of a dark figure lingering at the school gates, the hope died.

She had filled her head with excuses for him – that he was ill, the foot infection raging in his blood, or he was hiding out somewhere until the search died down. Or even that he had failed to retrieve the necklace at all and was too worried about loss of face to admit it. But she knew he’d have sent word, somehow. He’d have made sure she wasn’t left in the dark. He knew what the necklace meant to her. Just as she knew what it could mean to him. The image of him whipped and fettered in jail raced through her dreams at night.

And worse. Much worse. In just the same way that her father had protected her and had died for it in the snows of Russia, so now she’d been protected by Chang and he’d died for it. She saw his limp body tossed into a black and raging river, and she woke up moaning. But by daylight she knew better. The International Settlement was a hotbed of gossip and rumour, so if the jewel thief had been caught and the necklace reclaimed, she’d have heard.

He was a thief, damn it. Plain and simple. He’d taken the jewels and gone. So much for honour among thieves. So much for saving someone’s life. She was so angry with him, she wanted to scratch his eyes out and stomp on the foot she’d sewn up with such care, just to see him in pain as she was in pain. Her head was full of a harsh raw buzzing sound like the teeth of a saw biting into metal and she wasn’t sure whether that was rage or starvation. Repeatedly she was told off by Mr Theo for not paying attention in class.

‘A hundred lines, Lydia – I must not dream. Stay in and do them at break time.’

I must not dream.

I must not dream.

I must dream.

I dream.

I must

The words messed up her thoughts and took on colours of their own on the white ruled paper, so that dream seemed sometimes red and sometimes purple, swirling over the page. But not remained black as a mineshaft and she left it out all the way down the rows, making a deep drop for it, until right at the end when Mr Theo was holding out his hand for the paper. Quickly she scribbled in the missing nots. His mouth twitched with amusement, which only made the buzzing louder in her head, so she refused to look at him and stared instead at the ink stain the pen had made on her left forefinger. As black as Chang’s heart.

After school she threw off her uniform and her hat, pulled on an old dress – not the one with the bloodstains, she couldn’t bear to touch that one – and went in search of food for Sun Yat-sen. The park was the place. Any weeds that drew breath in the street were instantly torn up by hungry scavengers, but she’d found a rough bank in Victoria Park, where dandelions had taken over and remained untouched because no Chinese were allowed inside the railings. Sun Yat-sen loved the raggedy leaves and would hop in a flurry of white onto her lap while she fed them to him one by one. She worried about his food more than her own.

When she had filled her crumpled brown paper bag with leaves and grass, she headed over to the vegetable market in the Strand in the hope of picking up a few scraps under the stalls. The day was hot and humid, the pavement scorching the soles of her feet through her thin sandals, so she kept to the shade wherever she could and watched other girls twirling their dainty parasols or disappearing into La Fontaine Café for ice cream or to the Buckingham Tearoom for cool sherbets and cucumber sandwiches without crusts.

Lydia turned her head away. Averted her eyes and her thoughts. Things were not good at home at the moment. Not good at all. Valentina had not left the attic all week, not since the aborted concert, and seemed to be living on nothing but vodka and cigarettes. The musky smell of Antoine’s hair oil hung in the room but he was never there when Lydia came home, just the cushions in a mess on the floor and her mother in various stages of despair.

‘Darling,’ she’d murmured the day before, ‘it is time I joined Frau Helga’s, if she’ll have me.’

‘Don’t talk like that, Mama. Frau Helga’s is a brothel.’

‘So?’

‘It’s full of prostitutes.’

‘I tell you, little one, if no one will pay me for running my fingers over piano keys anymore, then I must earn money by putting my fingers to work elsewhere. That’s all they’re fit for now.’ She had held up her fingers, curled over like broken fans, for her daughter to inspect.

‘Mama, if you put them to work scrubbing the floor and hanging up your clothes, at least this place wouldn’t be such a pigsty.’

‘Poof!’ Valentina had dragged both hands through her wild hair and flounced back to bed, leaving Lydia reading in a chair by the window.

Sun Yat-sen was asleep bonelessly on her shoulder, his nose whispering his dreams into her ear. The book was one from the library, Hardy’s Jude the Obscure, and it was the third time she’d read it. Its abject misery brought her comfort. The room was a mess around her but she ignored it. She had arrived home from school yesterday to find Valentina’s clothes hurled across the floor and left there to be walked over. Signs of another row with Antoine. But this time Lydia refused to pick them up and carefully walked around them instead. It was like walking around dead bodies. And no food in the house. The few things she’d bought to eat with the watch money were long gone.

Lydia knew she should take her new dress up to Mr Liu’s, the beautiful concert frock with the low apricot satin sash. But she didn’t. Each day she told herself she’d do it tomorrow, for certain tomorrow, but the dress continued to hang on a hook on the wall while each day she grew thinner.

The Strand was emptying by the time Lydia arrived. The leaden heat had driven people off the street, but the vegetable market in the big noisy hall at the far end was busier than she’d expected this late in the day. The Strand was the main shopping area in the International Settlement, dominated by the gothic frontage of Churston Department Store where ladies bought their undergarments and gentlemen their humidors and Lydia could browse when it rained.

Today she hurried past it and into the market, in search of a stall closing down for the day, one where broken cabbage leaves or a bruised durian were being thrown into a pig bin as the floor was swept clean. But each time she spotted one, a litter of Chinese street urchins was there before her, squabbling and scrapping over the castoffs like kittens in a sack. After half an hour of patient scouting, she snatched up a corncob that a careless elbow had knocked to the floor and made a quick exit. She bundled the cob inside the paper bag along with the leaves and grass and had just stepped off the kerb to cross the road behind a swaying donkey cart when a hand snaked out and yanked the bag from her grasp.

‘Give that back,’ she shouted and grabbed for the scruff of the thief’s neck.

But the Chinese boy ducked under her arm and was off. His jet-black hair stood up like a scrubbing brush as he wove through the traffic, and though he could be no more than seven or eight years old he nipped in and out with the speed of a weasel. Diving, ducking, twisting. Lydia raced after him, barged around a corner, knocking into a juggler and sending his hoops flying, never taking her eyes off the scrubbing-brush head. Her lungs were pounding but she pushed harder, her legs stretching out in strides twice as long as the weasel’s. She was not going to let Sun Yat-sen go hungry tonight.

Abruptly the boy skidded to a halt. Twenty feet ahead, he turned and faced her. He was small, skin filthy, legs like twigs and an abscess under one eye, but he was very sure of himself. He held up the paper bag for a second, staring at her with his black unblinking eyes, and then opened his fingers and dropped the bag on the ground before backing off a dozen paces.

Only then did Lydia stop and look around. The street was quiet but not empty. A small maroon car with a dented fender was parked halfway down on her side, while two Englishmen were fiddling with a motorbike’s engine across the road. One was telling the other in a loud voice a joke about a mother-in-law and a parrot. This was an English street. It had net curtains. Not an alleyway in old Junchow. This was safe. So why did she feel unease claw its way into her mind? She approached slowly.

‘You filthy thieving devil,’ she yelled at him.

No answer.

Eyes fixed on him, she bent quickly, scooped up the bag from the ground, and held it tight to her chest, feeling the knobbly vegetable with her finger. But before she could work out what was going on, a hand came from behind, clamped over her mouth, and strong arms bundled her into the back of the small car with the dented fender. It all happened in the blink of an eye. But her own eye couldn’t blink. A knife blade was pushed against the top of the socket of her right eye and a harsh voice snarled something in Chinese.

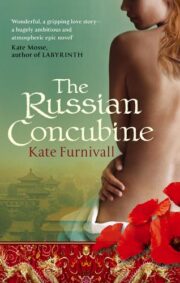

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.