At last the panic passed. Her body was trembling, her skin prickling with sweat, but she could breathe again. And think straight. That was important, the thinking straight.

The yard was very dark, crammed into a space only a few paces wide by high walls, and it smelled of mildew and things that were old. Mrs Zarya kept discarded furniture there that slowly decayed and mingled with the piles of rusty pans and ancient shoes. She was a woman who couldn’t bring herself to throw her things away. Lydia went up to a battered old tea chest that was lying on its side on top of a broken table, with wire mesh stretched across the opening. She put her face close to the wire.

‘Sun Yat-sen,’ she whispered. ‘Are you asleep?’

A shuffling, a snuffling, and then a soft pink nose pressed against hers. She unhooked the mesh and lifted the wriggling little body into her arms, where it settled down contentedly against her ribs, its nose pushed into the crook of her elbow. She stood there, cradling the small sleepy animal. An almost forgotten Russian lullaby from her childhood drifted from her lips and she gazed up at the dozen stars glittering far above her head.

Chang An Lo was gone. She had hidden the necklace in the club and believed him when he said he would bring it to her. But the temptation had been too much for him. She’d made a mistake. She wouldn’t make one again.

She tiptoed back up the stairs. No sound this time, her feet finding their way silently through the dark house, the warm bundle still tucked into her arm and her fingertips caressing the silky fur of its long ears and bony little body, its breath like feathers on her skin. She pushed open the attic door and was surprised to see the dim glow of her mother’s candle flickering behind the bedroom curtain. She scuttled over to her own end of the room, eager to hide Sun Yat-sen out of sight, but when she ducked round her curtain she stopped dead.

‘Mama,’ she said. Nothing more.

Her mother was standing there. Her nightdress askew, she was staring wide-eyed at Lydia’s empty bed. Her hair was a wild tangle around her shoulders and silent tears were pouring down her face. Her thin arms were wrapped tightly around her body as if she were trying to hold all the parts of it together.

‘Mama?’ Lydia whispered again.

Valentina’s head turned. Her mouth fell open. ‘Lydia,’ she cried out, ‘dochenka. I thought they had taken you.’

‘Who? The police?’

‘The soldiers. They came with guns.’

Lydia’s heart was racing. ‘Here? Tonight?’

‘They tore you from your bed and you screamed and screamed and hit one in the face. He pushed a gun into your mouth and knocked your teeth out and they dragged you outside into the snow and…’

‘Mama, Mama.’ Lydia rushed to wrap an arm around her mother’s trembling shoulders and held her close. ‘Hush, Mama, it was a dream. Just a horrible dream.’

Her mother’s body was ice cold and Lydia could feel the spasms that shook it, as though something were cracking up deep inside.

‘Mama,’ she breathed into the sweat-soaked hair. ‘Look at me, I’m here, I’m safe. We’re both safe.’ She drew back her lips. ‘See, I have all my teeth.’

Valentina stared at her daughter’s mouth, her eyes struggling to make sense of the images that crowded her brain.

‘It was a nightmare, Mama. Not real. This is real.’ Lydia kissed her mother’s cheek.

Valentina shook her head, trying to banish the confusion. She touched Lydia’s hair. ‘I thought you were dead.’

‘I’m here. I’m alive. We’re still together in this stinking rat hole with Mrs Zarya still counting her dollars downstairs and the Yeomans’ place still smelling of camphor oil. Nothing has changed.’ She pictured the rubies passing between Chinese hands. ‘Nothing.’

Valentina took a deep breath. Then another.

Lydia led her back to her own bed where the candle burned up the night with an uneven spitting flame. She tucked her between the sheets and gently kissed her forehead. Sun Yat-sen was still huddled against her, and his eyes, pink as a sugar mouse, were huge with alarm, so she kissed his head too, but Valentina did not even notice him.

‘I’ll leave the candle alight for you,’ Lydia murmured. It was a waste. One they could ill afford. But her mother needed it.

‘Stay.’

‘Stay?’

‘Yes. Stay with me.’ Valentina lifted the sheet.

Without a word Lydia slipped in and lay on her back, her mother on one side, her rabbit on the other. She kept very still in case Valentina changed her mind but watched the smoky shadows dance on the ceiling.

‘Your feet are like ice,’ Valentina said. She was calmer now and leaned her head against her daughter’s. ‘You know, I can’t remember the last time we were in bed together.’

‘It was when you were sick. You’d caught an ear infection and had that fever.’

‘Was it? That must be three or four years ago, the time when Constance Yeoman told you I might die.’

‘Yes.’

‘Stupid old witch. It takes more than a fever or even an army of Bolsheviks to kill me off.’ She squeezed her daughter’s hand under the sheets and Lydia held on to it.

‘Tell me about St Petersburg, Mama. About when the tsar came to visit your school.’

‘No, not again.’

‘But I haven’t heard that story since I was eleven.’

‘What a strange memory for dates you have, Lydochka.’

Lydia said nothing. The moment too fragile. Her mother’s guard could come up any minute and then she would be out of reach. Valentina sighed and hummed a snatch of Chopin’s Nocturne in E Flat. Lydia relaxed and felt Sun Yat-sen stretch out against her and rest his tiny chin on her breast. It tickled.

‘It was snowing,’ Valentina began. ‘Madame Irena made us all polish the floor till it gleamed like the ice on the windows and we could see our faces in it. That was instead of our French lesson. We were so excited. My fingers shook so much, I was frightened I couldn’t play. Tatyana Sharapova was sick at her desk and was sent to bed for the day.’

‘Poor Tatyana.’

‘Yes, she missed everything.’

‘But you were the one who should have been sick,’ Lydia prompted.

‘That’s right. I was the one chosen to play for him. The Father of Russia, Tsar Nicholas II. It was a great honour, the greatest honour a fifteen-year-old girl could dream of in those days. He chose us because our school was the Ekaterininsky Institute, the finest in all Russia, even finer than the ones in Kharkov or Moscow. We were the best and we knew it. Proud as princesses we were and carried our heads somewhere up near the clouds.’

‘Did he speak to you?’

‘Of course. He sat down on a big carved chair in the middle of the hall and told me to begin. I’d heard that Chopin was his favourite composer, so I played the Nocturne and poured my heart into it that day. And at the end he made no secret of the tears on his face.’

A tear trickled down Lydia’s cheek and she wasn’t sure who it belonged to.

‘We were all standing in our white capes and pinafores,’ Valentina continued, ‘and he came over to me and kissed my forehead. I remember his beard was bristly on my face and he smelled of hair wax, but the medals on his chest shone so bright I thought they’d been touched by the finger of God.’

‘Tell me what he said.’

‘He said, “Valentina Ivanova, you are a great pianist. One day you shall play the piano at court in the Winter Palace for me and the Dowager Empress, and you shall be the toast of St Petersburg.”’

A contented silence filled the room and Lydia feared her mother might stop there.

‘Did the tsar bring anyone with him?’ she asked, as if she did not know.

‘Yes, an entourage of elite courtiers. They stood over by the door and applauded when I finished.’

‘And was there anyone special among them?’

Valentina took a deep breath. ‘Yes. There was a young man.’

‘What did he look like?’

‘He looked like a Viking warrior. Hair that burned brighter than the sun, it lit up the room, and shoulders that could have carried Thor’s great axe.’ Valentina laughed, a light swaying sound that made Lydia think of the sea and Viking longboats.

‘You fell in love?’

‘Yes,’ Valentina answered, her voice soft and low. ‘I fell in love the moment I set eyes on Jens Friis.’

Lydia shivered with pleasure. It blunted the sharp ache inside her. She closed her eyes and imagined her father’s big smile and his strong arms folded across his broad chest. She tried to remember it, not just imagine it. But couldn’t.

‘There was someone else there too,’ Valentina said.

Lydia snapped open her eyes. This wasn’t part of the story. It ended with her mother falling in love at first sight.

‘Someone you’ve met.’ Valentina was determined to tell more.

‘Who?’

‘Countess Natalia Serova was there. The one who had the nerve to tell you last night that you should speak Russian. But where did speaking Russian get her, I’d like to know? Nowhere. When the Red dogs started biting, she was first in line on the trains out of Russia, her jewels intact, on the Trans-Siberian Railway, and didn’t even wait to learn whether her Muscovite husband was dead or alive before she wedded a French mining engineer here in Junchow. Though he’s off somewhere up north now.’

‘So she has a passport?’

‘Oh yes. A French one, by marriage. One of these days she’ll be in Paris on the Champs-Elysées, sipping champagne and parading her poodles while I rot and die in this miserable hellhole. ’

The story was spoiled. Lydia felt the moment of happiness fade. She lay still for a further minute watching the shadows dance, then said, ‘I think I’ll go back to my own bed now, if you’re all right.’

Her mother made no comment.

‘Are you all right now, Mama?’

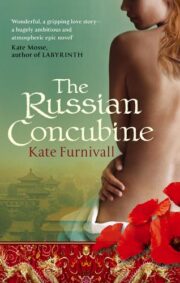

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.