‘Fetch the security guards,’ Parker shouted. ‘We had a robbery here last night. This person is…’

‘Empty your pockets,’ Theo repeated sharply.

For a moment he thought the boy was going to strike. Something in his eyes seemed to struggle free, something wild and angry, but then it was caged once more and the boy lowered his gaze. Without a word he tipped his pocket inside out, spilling its contents onto the tiled floor of the veranda. A large handful of salted peanuts skidded around their feet.

Theo laughed. ‘So much for your jewel thief, Alfred. The boy’s just hungry.’

But Parker was not ready to let go so easily. ‘And your other pockets.’

The boy did as he was told. A length of bamboo twine, a fishing hook wrapped in clay, and a folded sheet of paper covered in Chinese character writing. Theo picked it up and scanned it briefly.

‘What is it?’ Parker asked.

‘Nothing much. A poster for a gathering of some sort.’

But as the boy bent to retrieve his belongings, Theo caught a glimpse of the bone handle of a knife tucked into his belt, and suddenly he was frightened for his friend.

‘Let him go, Alfred. This is nothing to us. The boy was hungry. Most of China is hungry.’

‘A thief is a thief, Theo. Be it peanuts or jewels. Thou shalt not steal, remember?’ But he was no longer angry. His face looked sad, his spectacles sliding halfway down his nose. ‘We owe them that much, Theo. To teach them right from wrong, not just how to lay rail tracks and build factories.’

He reached out to take hold of the boy’s arm, but Theo intervened. He seized Parker’s wrist.

‘Don’t, Alfred. Not this time.’ He turned to the silent figure with the black eyes full of hatred. ‘Go,’ he said quickly in Chinese. ‘And don’t come back.’

The boy set off around the lawn, loping with an uneven stride into the trees that skirted the grounds, then he was gone. To Theo the image was of a creature returning to its jungle, and he wondered what had tempted it out into the open. Certainly not peanuts.

‘You might regret that,’ Parker said with an annoyed little shake of his head.

‘Mercy droppeth like the gentle rain from heaven,’ Theo said cynically and glanced again at the sheet of paper still in his hand. It was actually a Communist pamphlet.

‘Sha! Sha!’ it said. ‘Kill! Kill! Kill the hated imperialists. Kill the traitor Chiang Kai-shek. Long live the Chinese people.’

The words worried Theo more than he cared to admit. Chiang Kai-shek and his Kuomintang Nationalists had seized control and deserved now to be given a chance, if only the Western powers would back him against these troublemakers. The Communists would only do to China what Stalin was doing to Russia – turn it into a barren wasteland. China possessed too much beauty and too much soul to be stripped bare like a common whore. God preserve us from Communists. God and Chiang Kai-shek’s army.

‘Did he say yes?’

‘Yes.’

Li Mei kissed the nape of his neck. ‘I am happy for you, Tiyo. Parker is a good friend to you.’

She laid her cheek against his naked back, but her fingers did not cease their firm circular motion on each side of his spine, digging deep into the muscles. Theo was facedown flat on the floor in the bedroom while Li Mei massaged the tension from his body. He was always amazed at the strength of her fingers and how she knew just where to press the heel of her hand to release another demon from under his skin.

‘Yes, Alfred is a good friend, though some of his views are so narrow they would sit well on Oliver Cromwell.’

‘Oliver Cromwell? Tell me, who is this Oliver? Another friend?’

Theo laughed and felt her pound his shoulder blade with her knuckles.

‘You joke at me, Tiyo.’

‘No, my love, I am in awe of you.’

‘Now you lie. Bad Tiyo.’ She pummelled his buttocks with tight little fists that sent the blood surging to his loins. He rolled over and held her wrists, then stood and scooped her naked body up into his arms. She smelled of sandalwood and somehow of ice cream. He started to carry her down the stairs.

‘Alfred was furious that Mason is so corrupt. Appalled that he was trying to force me to help him break into the opium cartel. I swore to Alfred that just because your father runs it, it doesn’t mean I’m involved in any way. You know how I feel about drugs.’

‘An abomination, that’s what you call opium.’

He smiled and kissed her dark head. ‘Yes, my sweet one. An abomination. So he’s agreed to dig around in the bastard’s past and see if he can find anything that I can use to twist his arm.’

He entered the empty schoolroom, cradling her in his arms.

‘It is good it is Sunday.’ She laughed.

He lifted her higher and sat her, facing him, on his own tall desk in front of the rows of seats.

‘Now,’ he said, ‘when I stand here and talk to my pupils about Vesuvius tomorrow, I shall think of this.’ He leaned forward and kissed her left breast. ‘And this when I describe an equilateral triangle. ’ His lips clung to the nipple of her right breast. ‘And this when I tell the numbskulls about the moist dark heart of Africa.’ He lowered his head and kissed the black bush that rose at the base of her flat stomach.

‘Tiyo,’ she crooned into his hair, ‘Tiyo. Take care. This Mason, he is a man of power.’

‘He is not the only one with power,’ he said, and laughed. Gently he laid her down on the floor.

12

‘What is this?’

Valentina was standing in the middle of the room, pointing a rigid finger at a cardboard box on the floor. Lydia had just come home to find the attic even stuffier than usual. The windows were closed. It smelled different too. She couldn’t work out why.

‘You,’ Valentina said loudly, ‘should be ashamed of yourself.’

Lydia shuffled uncomfortably on the carpet, her mind spinning through answers. Ashamed. Of what? Of Chang? No, not him. So here she was again, back to the lies. Which lie?

‘Mama, I…’

She stared at her mother. Two high spots of colour burned on Valentina’s pale cheeks and her eyes were very dark, her pupils huge, her lashes heavy.

‘Antoine came over,’ Valentina declared, as if it were Lydia’s fault. ‘Look.’ The pointing finger flicked again in the direction of the box. ‘Look in there.’

Lydia approached carelessly. It was a striped hatbox with a bright red bow wrapped around it. She could not imagine why on earth her mother would be cross and making a ridiculous fuss about being given a hat. She loved hats. The bigger the better.

‘Is it a small one?’ she asked as she bent to lift the lid.

‘Oh, yes.’

‘With a feather?’

‘No feathers.’

Lydia removed the lid. Inside crouched a white rabbit.

‘Sun Yat-sen.’

‘What?’

‘Sun Yat-sen.’

‘What kind of name is that for a rabbit?’ Polly exclaimed.

‘He was the father of the Republic. He opened the door to a whole new kind of life for the people of China in 1911,’ Lydia said.

‘Who told you that?’

‘Chang An Lo.’

‘While you were sewing up his foot?’

‘Afterward.’

‘You are so brave, Lydia. I’d have died before I could stick a needle into someone’s flesh.’

‘No, you wouldn’t, Polly. You’d do it if you had to. There’s a lot of things we can do if we have to.’

‘But why not call the rabbit Flopsy or Sugar or even Lewis after Lewis Carroll? Something nice.’

‘No. Sun Yat-sen he is.’

‘But why?’

‘Because he’s opening the door to a whole new kind of life for me.’

‘Don’t be silly, Lyd. He’s only a rabbit. You’ll just sit and cuddle him, like I cuddle Toby.’

‘That’s what I mean, Polly.’

It was one-thirty in the morning. Lydia abandoned her chair at the window. He wasn’t coming.

But he might. Still he might. He could be in hiding somewhere, waiting for the night to…

No. He wasn’t coming.

Her tongue was thick and dry in her mouth. She’d been arguing with herself for hours, eyes glazed with tiredness. No amount of wanting was going to make him come. Chang An Lo, I trusted you. How could I have been so stupid?

In the pitch darkness of the room she made her way across to the sink and splashed cold water into her mouth. A low groan crawled out of her because the pain in her chest was more than she could bear. Chang An Lo had betrayed her. Just thinking the words hurt. Long ago she learned that the only person you can trust is yourself but she’d thought he was different, that they had a bond. They’d saved each other’s lives and she was so sure they had a… a connection between them. Yet it seemed that his promises were worth no more than monkey shit.

He knew that the necklace was her one chance to start again, a bright new life, in London or even in America where they said everyone was equal. A shining life. One without dark corners. Her chance to give back to her mother at least some of what the Reds had stolen from her. A grand piano with ivory keys that sang like angels and the finest mink coat, not one from Mr Liu’s, not second hand, but gleaming and new. Everything new. Everything. New.

She closed her eyes. Standing in the darkness, in bare feet and an old torn petticoat that had once belonged to someone else, she made herself accept that he was gone. And the ruby necklace with him. The shiny new life. With all its happiness. Gone.

She felt her throat tighten. Started to choke. No air inside her. Blindly she felt for the door. It caught her toe, scraped off the skin, but she pulled it open and raced down the two flights of stairs. To the back of the house. A door to the yard. She yanked at the bolt, again and again until at last it rattled free and she burst out into the cool night air. She took a mouthful of it. And another. She forced her lungs to work, to go on working, in and out. But it was hard. She tried to empty her head of the anger and despair and disappointment and fear and fury and all the wanting and needing and longing. And that was harder.

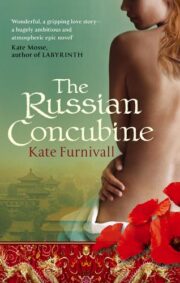

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.