‘Would it help if I did it?’ she asked.

He nodded again. He saw her swallow. Her soft pale throat seemed to quiver in a brief spasm, then settle.

‘You need a doctor.’

‘A doctor costs dollars.’

She said nothing more, but threw off her hat, letting loose the wonderful fox spirit of her hair, the way he’d once loosed the fox from the snare. She leaned over his foot. Not touching. Just looking. He could hear her breathing, in and out, feel it brush the jagged edges of his damaged flesh like the kiss of the river god.

He emptied his mind of the hot pain. Instead he filled it with the sight of the smooth arch of her high forehead and the copper glow of one lock of her hair that curled on the white skin of her neck. Perfection. Not pain. He closed his eyes and she started to sew. How could he tell her he loved her courage?

‘That’s better,’ she said, and he heard the relief in her voice.

She had removed her underskirt, quickly and without embarrassment, cut it into strips with his knife, and bound his foot into a stiff white bundle that would no longer fit inside his shoe. Without asking, she cut the shoe’s rubber sides, then tied it over the bandage with two more strips of cloth. It looked clean and professional. The pain was still there but at last the blood had stopped.

‘Thank you.’ He gave her a small bow with his head.

‘You need sulphur powder or something. I’ve seen Mrs Yeoman use it to dry up sores. I could ask her to…’

‘No, it is not needed. I know someone who has herbs. Thank you again.’

She turned her face away and trailed her hands through the water, fingers splayed out. She watched their movement as if they belonged to someone else, as if she were surprised by what they had done today.

‘Don’t thank me,’ she said. ‘If we go around saving each other’s lives, then that makes us responsible for each other. Don’t you think?’

Chang was stunned. She had robbed his tongue of words. How could a barbarian know such things, such Chinese things? Know that this was the reason he had followed her, watched over her. Because he was responsible for her. How could this girl know that? What kind of mind did she possess that could see so clearly?

He felt the loss of her from his side when she rose to her feet, kicked off her sandals, and waded into the shallows. A golden-headed duck, startled from its slumber in the reeds, paddled off downstream as fast as if a stoat were on its tail, but she scarcely seemed to notice, her hands busy splashing water over the hem of her dress. It was a shapeless garment, washed too many times, and for the first time he saw the blood on it. His blood. Entwined in the fibres of her clothes. In the fibres of her. As she was entwined in the fibres of him.

She was silent. Preoccupied. He studied her as she stood in the creek, her skin rippling with silver stars reflected from the water, the sunlight on her hair making it alive and molten. Her full lips were slightly open as if she would say something, and he wondered what it might be. A heart-shaped face, finely arched brows, and those wide amber eyes, a tiger’s eyes. They pierced deep inside you and hunted out your heart. It was a face no Chinese would find alluring, the nose too long, the mouth too big, the chin too strong. Yet somehow it drew his gaze again and again, and satisfied his eyes in ways he didn’t understand but in ways that contented his heart. But he could see secrets in her face. Secrets made shadows, and her face was full of pale breathless shadows.

He lay back on the warm grass, resting on his elbows.

‘Lydia Ivanova,’ he said quietly. ‘What is it that is such trouble to you?’

She lifted her gaze to his and in that second when their eyes fixed on each other, he felt something tangible form between them. A thread. Silver and bright and woven by the gods. Shimmering between them, as elusive as a ripple in the river, yet as strong as one of the steel cables that held the new bridge over the Peiho.

He lifted a hand and stretched it out to her, as if he would draw her to him. ‘Tell me, Lydia, what lies so heavy on your heart?’

She stood up straight in the water, letting go of the edge of her dress so that it floated around her legs like a fisherman’s net. He saw a decision form in her eyes.

‘Chang An Lo,’ she said, ‘I need your help.’

A breeze swept in off the Peiho River. It carried with it the stench of rotting fish guts. It came from the hundreds of sampans that crowded around the flimsy jetties and pontoons that clogged the banks, but Chang was used to it. It was the stink of boiled cowhide from the tannery behind the godowns around the harbour.

He moved quickly. Shut his mind to the knives in his foot and slipped silently past the noisy, shouting, clattering world of the riverside, where tribes of beggars and boatmen made their homes. The sampans bobbed and jostled each other with their rattan shelters and swaying walkways, while cormorants perched, tethered and starved, on the prows of the fishermen’s boats. Chang knew not to linger. Not here. A blade between ribs, and a body to add to the filth thrown daily into the Peiho, was not unheard of for no more than a pair of shoes.

Out where the great Peiho flowed wider than forty fields, British and French gunboats rode at anchor, their white and red and blue flags fluttering a warning. At the sight of them Chang spat on the ground and trampled it into the dirt. He could see that half a dozen big steamers had docked in the harbour, and near-naked coolies bent double as they struggled up and down the gangplanks under loads that would break the back of an ox. He kept clear of the overseer who strutted with a heavy black stick in his hand and a curse on his tongue, but everywhere men shouted, bells rang, engines roared, camels screamed, and all the time in and out of the chaos wove the rickshaws, as numerous as the black flies that settled over everything.

Chang kept moving. Skirted the quayside. Ducked down an alleyway where a severed hand lay in the dust. On to the godowns. These were huge warehouses that were well guarded by more blue devils, but behind them a row of lean-to shacks had sprung up. Not shacks so much as pig houses, no higher than a man’s waist and built of rotting scraps of driftwood. They looked as if a moth’s wings could blow them away. He approached the third one. Its door was a flap of oilcloth. He pulled it aside.

‘Greetings to you, Tan Wah,’ he murmured softly.

‘May the river snakes seize your miserable tongue,’ came the sharp reply. ‘You have stolen away my soft maidens, skin as sweet as honey on my lips. Whoever you are, I curse you.’

‘Open your eyes, Tan Wah, leave your dreams. Join me in the world where the taste of honey is a rich man’s pleasure and a maiden’s smile a million li away from this dung heap.’

‘Chang An Lo, you young son of a wolf. My friend, forgive the poison of my words. I ask the gods to lift my curse and I invite you to enter my fine palace.’

Chang crouched down, slipped inside the foul-smelling hovel, and sat cross-legged on a bamboo mat that looked as if it had been chewed by rats. In the dim interior he could make out a figure wrapped in layers of newspaper lying on the damp earth floor, his head propped on an old car seat cushion as a pillow.

‘My humble apologies for disturbing your dreams, Tan Wah, but I need some information from you.’

The man in the cocoon of newspaper struggled to sit up. Chang could see he was little more than a handful of bones, his skin the telltale yellow of the opium addict. Beside him lay a long-stemmed clay pipe, which was the source of the sickly smell that choked the airless hut.

‘Information costs money, my friend,’ he said, his eyes barely open. ‘I am sorry but it is so.’

‘Who has money these days?’ Chang demanded. ‘Here, I bring you this instead.’ He placed a large salmon on the ground between them, its scales bright as a rainbow in the dingy kennel. ‘It swam from the creek straight into my arms this morning when it knew I was coming to see you.’

Tan Wah did not touch it. But the narrow slits of his eyes were already calculating its weight in the black paste that would bring the moon and the stars into his home. ‘Ask what you will, Chang An Lo, and I will kick my worthless brain until it finds what you wish to know.’

‘You have a cousin who works at the fanqui’s big club.’

‘At the Ulysses?’

‘That is the one.’

‘Yes, my stupid cousin, Yuen Dun, a cub still with his milk teeth, yet he is growing fat on the foreigners’ dollars while I…’ He closed his mouth and his eyes.

‘My friend, if you would eat the fish instead of trading it for dreams, you might also grow fat.’

The man said nothing but lay back on the floor, picked up the pipe, and cradled it on his chest like a child.

‘Tell me, Tan Wah, where does this stupid cousin of yours live?’

There was a silence, filled only by the sound of fingers stroking the clay stem. Chang waited patiently.

‘In the Street of the Five Frogs.’ It was a faint murmur. ‘Next to the rope maker.’

‘A thousand thanks for your words. I wish you good health, Tan Wah.’ In one swift movement he was crouching on his feet ready to leave. ‘A thousand deaths,’ he said with a smile.

‘A thousand deaths,’ came the response.

‘To the piss-drinking general from Nanking.’

A chuckle, more like a rattle, issued from the newspapers. ‘And to the donkey-fucking Foreign Devils on our shore.’

‘Stay alive, friend. China needs its people.’

But as Chang pushed away the cloth flap, Tan Wah whispered urgently, ‘They are hunting you, Chang An Lo. Do not turn your back.’

‘I know.’

‘It is not good to cross the Black Snake brotherhood. You look as if they have already fed your face to their chow-chows to chew on. I hear that you stole a girl from them and crushed the life out of one of their guardians.’

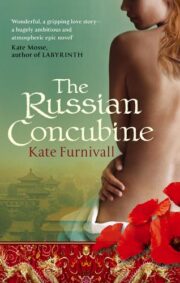

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.