A snarl. It spoke of death.

On the wet grass at his feet a wolf-dog was crouched, its body hunched ready to spring, its teeth bared in a low-throated growl that made Chang’s blood choke in his veins. The hound hungered to tear his heart out.

He did not want to kill the dog, but he would.

Slowly Chang turned his gaze from the animal to the man. He was wearing a blue-devil cape against the rain and was tall, with long gangling limbs and empty cheeks, the kind of tree it was easy to fell. In his hand was a gun. Chang could see his own blood glistening on it. The man’s thin lips were moving but the wind seemed to be roaring in Chang’s ears and he could barely hear the words.

‘Yellow piece of shit.’

‘Thieving Chink.’

‘Peeping Tom.’

‘Don’t you stare at our women, you bloody…’ And the gun rose to strike once more.

Chang dipped to one side and rotated his waist, and like the crack of a bullwhip his leg snapped out in an upward strike. But the dog was fast. It hurled itself between attacker and master and sank its teeth into the vulnerable flesh of Chang’s foot, forcing him onto his back on the wet earth. Pain raced up his leg as fangs tore at bone. But he inhaled, letting go of the tension in his body, and instead controlled the energy of the fear. He released it in one rippling movement that sent his other foot exploding into the face of the hound.

The animal dropped its grip and collapsed on its side without a whimper. Instantly Chang was up on his feet and running before the night had even drawn breath.

‘Take one more step and I put a bullet in your bloody brain.’ Chang stilled his mind. He knew this man was going to kill him for what he’d done to the dog. It had robbed the blue devil of face. So to stay or to flee made no difference, the end would be the same. He felt a knifepoint of regret in his lungs at leaving the girl. Slowly he turned and faced the man, saw the violence in his face and the steadiness of the black eye of the gun.

‘Dong Po, what on earth do you think you’re doing?’

The voice burst through the rain and cut the thread that joined the policeman’s bullet to Chang’s brain. It was the girl.

‘I told you to wait inside the gate, you worthless boy. I shall get Li to give you a good beating for disobedience when we get home.’ She was glaring at Chang.

At that moment Chang’s heart stopped. It took all his strength to prevent a wide smile from growing on his lips, but instead he ducked his head in humble apology.

‘I sorry, mistress, so sorry. No be angry.’ He gestured at the window. ‘I look for you to see okay. So much police, I worry.’

Behind the girl stood another blue devil. He was trying to hold a black umbrella over her head, but the rain and the wind were snatching at it, so that her hair hung in rats’ tails and had turned the colour of old bronze. Over her shoulders was thrown a servant’s thin white jacket, but already it was wet through.

‘Ted, what’s up with the dog?’ The second policeman was middle-aged and heavy.

‘I’m telling you, Sarge, if this yellow bugger has killed my Rex, I’ll…’

‘Ease up, Ted. Look, the dog’s moving, just stunned probably.’ He turned to Chang, noting the blood on his face. ‘Now look, boy,’ he said, not unkindly, ‘I’m not sure what’s gone on here but your mistress got real upset, she did, when she saw you skulking around these windows. She says you were told to wait at the gate, to act as escort, see, for her and her mother when they need one of them rickshaws. Those rickshaw buggers are right dangerous, so you should be ashamed of yourself, letting her down like this.’

Chang stared in silence at his bloodstained foot and nodded.

‘No discipline,’ said the blue devil, ‘that’s the trouble with you lot.’

Chang pictured sending a tiger-paw punch into his face. Would that show him discipline enough? If he’d intended the dog to be dead, it would be dead.

‘Dong Po.’

He looked up into her amber eyes.

‘Get off home right now, you miserable boy. You aren’t to be trusted, so tomorrow you shall be punished.’

She was holding her chin high and could have been the Grand Empress Tzu Hsi of the Middle Kingdom the way she gazed at him with haughty disdain.

‘Officer,’ she said, ‘I apologise for my servant’s behaviour. Please see that he’s thrown out of the gate, will you?’

Then she started walking back along the path as if she were taking a stroll in the sunshine instead of in a raging summer storm. The blue sergeant followed with the umbrella.

‘Mistress,’ Chang called after her against the roar of the wind.

She turned. ‘What is it?’

‘There no need to kill mosquito with cannon,’ he said. ‘Please be merciful. Say where I be punished tomorrow.’

She thought for a second. ‘For that added insolence, it will be at St Saviour’s Hall. To cleanse your wicked soul.’ She stalked off without a backward glance.

The fox girl’s tongue was cunning.

9

‘Mama?’

Silence. Yet Lydia was sure her mother was awake. The attic room was pitch black and the street outside lay quiet, cooler after the storm. From under Lydia’s bed came a faint scratching sound that she knew meant a mouse or a cockroach was on its nightly prowl, so she drew her knees to her chin and curled up in a tight ball.

‘Mama?’

She had heard her mother tossing and turning for hours in her small white cell and once caught the soft sniffing that betrayed tears.

‘Mama?’ she whispered again into the blackness.

‘Mmm?’

‘Mama, if you had all the money in the world to buy yourself one present, what would it be?’

‘A grand piano.’ The words came out with no hesitation, as if they had been waiting on the tip of her tongue.

‘A shiny white one like you said they have in the American hotel on George Street?’

‘No. A black one. An Erard grand.’

‘Like you used to play in St Petersburg?’

‘Just like.’

‘It might not fit in here very well.’

Her mother laughed softly, the sound muffled by the curtains that divided the room. ‘If I could afford an Erard, darling, I could afford a drawing room to put it in. One with hand-woven carpets from Tientsin, beautiful candlesticks of English silver, and flowers on every table filling the room with so much perfume it would rid my nostrils of the filthy stench of poverty.’

Her words seemed to fill the room, making the air suddenly too heavy to breathe. The scratching under the bed ceased. In the silence, Lydia hid her face in her pillow.

‘And you?’ Valentina asked when the silence had lasted so long it seemed she had fallen asleep.

‘Me?’

‘Yes, you. What present would you buy yourself?’

Lydia shut her eyes and pictured it. ‘A passport.’

‘Ah yes, of course, I should have guessed. And where would you travel with this passport of yours, little one?’

‘To England, to London first and then to somewhere called Oxford, which Polly says is so beautiful it makes you want to cry and then…’ her voice grew low and dreamy as if she were already elsewhere, ‘to America to see where they make the films and also to Denmark to find where…’

‘You dream too much, dochenka. It is bad for you.’

Lydia opened her eyes. ‘You brought me up as English, Mama, so of course I want to go to England. But tonight a Russian countess told me…’

‘Who?’

‘Countess Serova. She said…’

‘Pah! That woman is an evil witch. To hell with her and what she said. I don’t want you talking to her again. That world is gone.’

‘No, Mama, listen. She said it is disgraceful that I can’t speak my mother tongue.’

‘Your mother tongue is English, Lydia. Always remember that. Russia is finished, dead and buried. What use to you would learning Russian be? None. Forget it, like I have forgotten it. And forget that countess too. Forget Russia ever existed.’ She paused. ‘You will be happier that way.’

The words flowed out of the darkness, hard and passionate, and beat like hammers on Lydia’s brain, pounding her thoughts into confusion. Part of her longed to be proud of being Russian, the way Countess Serova was proud of her birthright and of her native tongue. But at the same time Lydia wanted so much to be English. As English as Polly. To have a mother who toasted you crumpets for tea and went around on an English bicycle and who gave you a puppy for your birthday and made you say your prayers and bless the king each night. One who sipped sherry instead of vodka.

She put a hand to her mouth. To stop any sounds coming out, in case they were sounds of pain.

‘Lydia.’

Lydia had no idea how long the silence had lasted this time, but she started to breathe heavily as if asleep.

‘Lydia, why did you lie?’

Her chest thumped. Which lie? When? To whom?

‘Don’t pretend you can’t hear me. You lied to the policeman tonight.’

‘I didn’t.’

‘You did.’

‘No, I didn’t.’

A sharp pinging of bedsprings from the other end of the room made Lydia fear that her mother was on her way over to confront her daughter face to face, but no, she was just shifting position impatiently in the darkness.

‘Don’t think I don’t know when you’re lying, Lydia. You tug at your hair. So what were you up to, spinning such a story to Police Commissioner Lacock? What is it you’re trying to hide?’

Lydia felt sick, not for the first time tonight. Her tongue seemed to swell and fill her mouth. The church clock struck three and something squealed at the end of the street. A pig? A dog? More likely a person. The wind had died down, but the stillness didn’t make her feel any better. She started counting backward from ten in her head, a trick she’d learned to ward off panic.

‘What story?’ she asked.

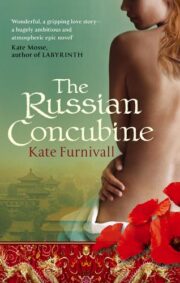

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.