Lydia stared at the floor, unwilling to admit she didn’t understand.

‘Oh, but Lydia doesn’t speak Russian,’ Anthea Mason said helpfully.

The countess raised one skilfully arched eyebrow. ‘No Russian? And why not?’

Lydia felt like digging a hole in the floor and climbing into it. ‘My mother brought me up to speak only English. And a little French,’ she added quickly.

‘That is disgraceful.’

‘Oh, Countess, don’t be so harsh on the girl.’

‘Kakoi koshmar! She should know her mother tongue.’

‘English is my mother tongue,’ Lydia insisted, though her cheeks were burning. ‘I’m proud to speak English.’

‘Good for you,’ said Anthea Mason. ‘Fly the flag, my dear.’

The countess reached out, tucked a finger under Lydia’s chin, and lifted it an inch. ‘That is how you would hold it,’ she said with an amused smile on her lips, ‘if you were at court.’ Her Russian accent was even stronger than Valentina’s, so that the words seemed to roll around inside her mouth, and she gave a little shrug of her shoulders but her cool gaze examined Lydia intently, so that Lydia felt she was being peeled, layer by layer. ‘Yes, you are a lovely child, but…,’ Countess Serova dropped her hand and moved back, ‘far too thin to wear a dress like that. Enjoy your evening.’ She seemed to glide away across the hall with her companion.

‘I heard today that Helen Wills has won Wimbledon,’ Anthea was saying. ‘Isn’t it thrilling?’ She gave an apologetic little wave in Lydia’s direction.

For a full minute Lydia didn’t move. The hall was filling up as the evening grew busier but there was still no sign of her mother. A sharp pain had lodged just behind her breastbone and misery had soiled the new dress like a grubby stain. She was now acutely aware that she was all bones sticking out, her breasts too small and her hair the wrong colour. Too spiky in her mind, as well as her body. She was masquerading in the dress, just as she was masquerading at being English. Oh yes, she spoke it with a perfect English accent, but who did that fool?

At the end of a minute she raised her chin an inch, then went in search of her mother because the recital was due to start at eight-thirty.

The two figures stood close to each other. Too close, it seemed to Lydia. One, small and slender in a blue dress, had her back against the wall of a passageway, the other, broader and needier, was leaning over her, his face almost touching hers, as if he would eat her up.

Lydia froze. She was halfway down a well-lit corridor inside the club, but off to the right ran the narrow passageway that looked as though it led to somewhere like the servants’ quarters or the laundry. Somewhere hidden away. It was dim and over-warm, the large potted palm at its entrance throwing long shadowy fingers snaking along the tiled floor. She knew her mother instantly. But the man leaning over her took longer to place. With a shock she realised it was Mr Mason, Polly’s father. His hands were all over her mother, all over the blue silk. On her thighs, her hips, her throat, her breasts. As if he owned them. And she did nothing to push him away.

Lydia felt a swirl of sickness in her stomach. She longed to turn, to break the pull of it, but couldn’t, so she stood there, watching, unable to drag her eyes away. Her mother stood absolutely still, her back and her head and the palms of her hands pressed against the wall behind her, as if she would climb right through it. When Mason’s mouth seized Valentina’s, she let it happen but the way a doll lets its face be washed. Taking no part, eyes open and glazed. With both his hands clutching her body against his, Mason slid his mouth down her neck to the warm cleft between her breasts, and Lydia heard his groan of pleasure.

A small gasp escaped Lydia’s mouth, she couldn’t help it. Even though it was low and stifled, it was enough to make her mother twist her head. Her huge dark eyes widened when they fixed on her daughter’s and her mouth opened, but no sound came out. Lydia’s legs at last responded and she stepped back out of sight, into the corridor where she raced back around one corner and then another. Somewhere behind her she heard her mother’s voice. ‘Lydia, Lydia.’

That was when she saw someone she knew, a man she was sure she’d met somewhere before. He was heading for the main exit but his face was turned in Lydia’s direction. It was the man whose watch she’d stolen yesterday in the marketplace. Without thinking, she burst through the first door on the left and shut it behind her. The room was small and silent, a cloakroom, full of rows of coats and stoles, capes and Burberrys, as well as racks of top hats and walking canes. Off to one side was a small archway into a separate area where an attendant waited at a counter to receive or retrieve the guests’ outer garb. The attendant was not in sight at the moment but Lydia could hear him talking to someone in Mandarin.

She was trembling, her knees shaking beneath her, her teeth rattling in her head. She took a deep breath, made herself walk over to a glorious red fox wrap that hung nearby. Gently she rested her cheek against it and tried to calm her heaving stomach with the rich warmth of gleaming fur. But it didn’t work. She slid to the floor and wrapped her arms around her shins, rested her forehead on her knees, and tried to make sense of the evening.

Everything had gone wrong. Everything. Somehow everything had changed inside her head. All back to front. Her mother. Her school. Her plans. The way she looked. Even the way she spoke. Nothing was the same. And Mason with her mother. What was that about? What was going on?

She felt tears burn her cheeks and dashed them away furiously. She never cried. Never. Tears were for people like Polly, people who could afford them. With a shake of her head, she rubbed a hand across her mouth, jumped to her feet, and forced herself to think straight. If everything was wrong, then it was up to her to put it right. But how?

With hands still shivering, she brushed the creases from her dress and, more out of habit than intention, started to hunt through the pockets of the coats in the cloakroom. A pair of men’s leather gloves and a Dunhill lighter quickly came to hand but she put them back, even though it hurt to do so. She had nowhere to keep them, no evening bag or pocket, but a lady’s lace handkerchief she tucked into her underclothes; it would sell easily in the market. Next, a heavy black raincoat, still wet from the rain, a bulge in the inner pocket. Her fingers scooped out the contents. A soft pouch of deerskin.

Quickly, before someone comes. Loosen its neck, tip it upside down. Into her hand tumbled a glittering ruby necklace, lying like a pool of fiery blood in the centre of her palm.

8

Chang watched.

They came like a wave. Up from the heart of the settlement. A dark tidal wave of police that suffocated the street. With guns snug on their hips and badges proud on their peaked caps, as threatening as a cobra’s splayed hood. They leaped from cars and trucks, headlights carving the night into neat yellow slices, and they circled the club. A man in black and white finery, with medals bristling on his chest and a single glass lens over his right eye, strode down the steps toward them. He threw orders and gestures around, the way a mandarin scattered gold coins at his daughter’s wedding.

Chang watched, his breath cool and unhurried. But his thoughts probed the darkness, feeling for danger. He slid away. From the shadow of the tree and into the blackness while around him others scampered out of sight. The beggars, the vendor of sunflower seeds and the hot-tea seller, the boy, thin as a twig, performing backflips for pennies, all melted away at the first stink of police boots. The night air turned foul in Chang’s lungs and he could almost hear the cloud of angry nightspirits flitting and flickering past his head as they fled from yet one more barbarian invasion.

The rain still fell, heavier now, as if it would wash them away. It polished the streets and bowed the heads of the blue-uniformed devils, streaked their capes as they stationed themselves along the perimeter wall of the Ulysses Club. Chang watched as the man with the glass at his eye was swallowed up inside the building’s hungry mouth and the heavy doors closed behind him. An officer holding a rifle was placed in front of them. The world was shut out. The occupants shut in.

Chang knew she was in there, the fox girl, walking through its rooms the way she walked through his dreams while he slept. Even by day she appeared in his head, making herself at home there and laughing when he tried to push her out. He closed his eyes and could see her face, her sharp teeth and her flaming hair, her eyes the colour of molten amber, and the way they seemed to gleam from within when she’d looked at him, so bright and curious.

What if she didn’t want to be shut in the white devil’s building? Caged. Trapped. He had to loosen the snare.

He eased away from the wet bricks behind him and set off through the darkness at a low run, as silent and unseen as a cat snaking toward a rat hole.

He crouched. Invisible under a broad-leafed bush, while his eyes adjusted to the blackness at the back of the building. A high stone wall girded its grounds but no streetlights reached out to disturb the habits of the night. His quick ears caught the sharp screech of a creature in pain, in the talons of an owl or the jaws of a weasel, but the rattling of the rain on the leaves drowned out most other sounds. So he crouched and waited patiently.

He did not need to wait long. The round yellow beam of a flashlight announced the patrol of two police officers, with heads bent and shoulders hunched against the heavy rain as if it were an enemy. They hurried past, scarcely a glance around, though the beam danced from bush to bush like a giant firefly. Chang tipped his head back, lifting his face to the downpour, the way he used to do in the waterfall as a child. Water was a state of mind. If you think it your friend when you swim in the river or wash away the dirt, why call it your enemy when it comes from the heavens? From the cup of the gods themselves. Tonight it was their gift to him, to keep him safe from barbarian eyes, and his lips murmured a prayer of thanks to Kuan Yung, the goddess of mercy.

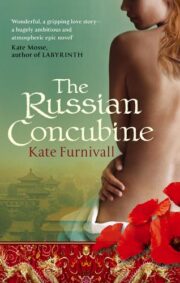

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.