6

Outside the Ulysses Club, the streetlamps of Wellington Road cast yellow pools of light out into the darkness. But the darkness of this country was vast and dense. It claimed for itself the fragile world the foreigners thought was theirs.

The darkness gave sanctuary. To the narrow-eyed thief who stood at the bedside of the young major’s sleeping child while his amah played mah-jongg downstairs. To the stinking honey wagon, the cart piled high with human manure destined for the fields. To the knife at the throat of a white man who thought a debt to a Chinese bookie was not binding.

And to Chang An Lo. As evening closed in, he was invisible in the darkness, his shadowy young figure merged with the mottled trunk of one of the plane trees that lined the road. He didn’t move. Even when a silver streak of lightning carved through the sky and rain sheeted down, making the leaves clatter above his head and the cars turn into glistening black monsters as their headlights swung through the wrought-iron gates of the club. A military guard with peaked cap and rifle checked every entrant.

Chang An Lo leaned his head back against the rough bark and shut his eyes to recapture the sight of the girl as she jumped down from the rickshaw that had carried her here. He pictured again the fire in her hair as it danced around her shoulders, the excitement in her step. He’d watched her face lift to study the giant marble pillars and his sharp eyes noticed the moment’s hesitation of her feet. Were her eyes still as full of astonishment, he wondered, as when he saw her yesterday? In the filthy hutong, the back alley.

Why had she come to that alley?

He’d asked himself that question many times. Had she strayed by accident? But how could you wander into the old Chinese town without noticing? Yet the ways of the fanqui were strange, the paths of their mind smudged and indecipherable. He rubbed a hand over the dense black stubble of his hair, felt the wet sheen of rain on it and pressed his fingers harder into his skull as if he could drag an answer from within it by force alone.

Was it the gods who had brought her to him?

He shook his head, angry with himself. The Europeans were no friend to the Chinese, and the gods of the Middle Kingdom would have nothing to do with them. Chang An Lo himself would have nothing to do with them except to drive their voracious souls back into the sea from which they came, but the strange thing was that when he saw her in the hutong yesterday, he didn’t see a Foreign Devil. Instead he saw a snarling, snapping fox. Like the one he once freed from a snare in the woods. It had sunk its teeth into him and torn a strip of flesh out of his arm, but it had fled to safety. At that time Chang had caught a glimpse of himself in the animal, trapped and fierce and fighting for its freedom.

And now there was this girl. With that same wildness. A fire raging inside her, as well as in her copper hair and in her wide fanqui eyes. She would burn him. He was as certain of it as he’d been that the snared fox would savage him when he touched it. But now he was bound to her, his soul to her soul, and he had no choice. Because he’d saved her life.

In his mind rose the image of the alleyway, a foul degrading sewer that no one would choose to enter. He would have passed it without a glance. But the gods stopped his stride and turned his head. She lit up the whole stinking black hole with her fire. His eyes had never before seen anyone like her.

Abruptly his thoughts were dragged back to the rain and the rumbling night sky, his attention distracted by the sound of footfalls and the brisk tap of a cane, a man passing only a few feet away. He wore a top hat and heavy raincoat, huddled under an umbrella, and hurried past Chang without even knowing he was there. But before he reached the club two shapes threw themselves at his feet on the sodden pavement.

Beggars, a man and a woman. Natives of the old town, their voices raised in high-pitched pleas.

Chang spat on the ground at the sight of them.

The man threw a handful of coins at the ragged creatures with a guttural curse, then brought his cane whistling down on their backs as they grovelled for them. Chang watched him walk away. Up the wide white steps and in through the entrance, so grand it looked like a mandarin’s palace. He didn’t hear the man’s words, but he knew the actions. He’d seen them all his life in China.

For the next hour his gaze was drawn again and again to the tall, brightly lit windows, as a bird is drawn to yellow corn. She was in there, the fox-haired girl. He’d watched her mount the steps with the other woman beside her, but between them the gap of unused air bristled with an anger that made their shoulders stiff and their heads turn away from each other.

He smiled to himself as the rain ran down his face. The fox girl, she had sharp teeth.

7

Lydia moved through the club quickly. There was little time and much to see.

‘Stay here. I won’t be long, ten minutes, that’s all,’ Valentina had said. ‘Don’t move.’

They were standing to one side of the sweeping staircase, where an antique oak settle seemed somewhat at odds with the brilliance of the chandelier overhead and the polished newel post in the shape of a giant acorn. Everything was on such a huge scale: the paintings, the mirrors, even the moustaches. Bigger and better than Lydia had ever seen before. Not even Polly had been inside the club.

‘And don’t speak to anyone,’ Valentina added, her voice sharp as she glanced around at the interested eyes and saw the men murmur to each other. ‘Not to anyone, you hear?’

‘Yes, Mama.’

‘I have to go to the office to see what the arrangements are for this evening.’ She gave a discouraging glare to a young man in evening dress and silk scarf who was drifting closer. ‘Maybe I should take you along with me.’

‘No, Mama, I’m fine here. I like watching everyone.’

‘The trouble is, Lydochka, they like watching you.’ She hesitated, undecided, but Lydia sat down demurely on the settle, hands in lap, so Valentina gave her a squeeze on the shoulder and walked off toward a corridor on the right. As she left, Lydia heard her mutter, ‘I should never have bought her that bloody dress.’

The dress. Lydia touched the soft apricot georgette with her fingertips. She loved it more than her life. She had never owned anything so beautiful. And the cream satin shoes. She lifted a foot and admired it. This was the most perfect moment of her life, sitting here in a beautiful place, dressed in beautiful clothes, while beautiful people looked admiringly at her. Because their eyes were admiring. She could see that.

This was living. Not just surviving. This was… this was being alive, instead of half dead. And for the very first time she thought she really understood a little of the pain that burned in her mother’s heart. To lose all this. It must be like blundering blindly into one of the sewers and making your home with the rats. Home. For a moment Lydia felt the pulse at her wrist start to thump. Home was the attic. But for how much longer? She took a handful of the apricot material and scrunched it up hard in her fist. Her feet slipped under the seat so that the shoes were hidden from view.

Look what I’ve bought you, darling. For tonight. For your birthday.

When Valentina said those words so full of delight after Lydia had rushed home from school this afternoon, Lydia smiled and expected a ribbon for her hair or even her first pair of silk stockings. Not this. This dress. These shoes.

She had frozen. Unable to move. Unable to swallow. ‘Mama,’ she said, her eyes fixed on the dress. ‘What did you use to pay for it?’

‘The money in the blue bowl on the shelf.’

‘Our rent and food money?’

‘Yes, but…’

‘All of it?’

‘Of course. It was expensive. But don’t look so upset.’ Valentina suddenly broke off and her bright eyes grew full of concern. She touched her daughter’s cheek. ‘Don’t worry so, dochenka,’ she said softly. ‘I will be paid well for my concert tonight and maybe it will bring me other bookings, especially with you looking so pretty at my side. See it as an investment in our future. Smile, sweetheart. Don’t you love the dress?’

Lydia’s head nodded but only a tiny movement, and her lips wouldn’t smile however hard she tried. ‘We’ll starve,’ she whispered.

‘What rubbish.’

‘We’ll rot in the gutter when Mrs Zarya throws us out.’

‘Darling, you are being melodramatic. Here, try it on. And the shoes. I still owe payment for the shoes but they are so pretty. Don’t you think?’

‘Yes.’ She could barely breathe.

But the moment the dress floated down over her head, she fell in love with it. Two delicate rows of beading lined the armholes and the geometric neckline, a sash of shimmering satin at the hips and a daring little slit up one side to just above the knee. Lydia twirled round in it, feeling it rustle against her body and give off the faintest scent of apricots. Or was that in her head?

‘Like it, darling?’

‘I love it.’

‘Happy birthday.’

‘Thank you.’

‘Now stop being cross with me.’

‘Mama,’ Lydia said softly, ‘I’m frightened.’

‘Poof, don’t be so silly. I buy you your first elegant dress to make you happy and you say you are frightened. To own something beautiful is not a crime.’ She leaned her dark head against Lydia’s and whispered, ‘Enjoy it, my beautiful young daughter, learn to enjoy what you can in this life.’

But all Lydia could do was shake her head. She loved the dress, yet hated it. And she despised herself for wanting it so much.

‘You make me cross, Lydia Ivanova, cross as an old goat,’ her mother said in a stern voice. ‘You don’t deserve the dress. I shall take it back.’

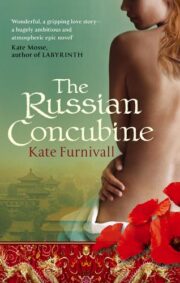

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.