Warrin swallowed his anger and bent carefully to lift Heulwen from the bottom of the boat. The craft tipped and reeled. Heulwen kept her eyes closed but could not feign unconsciousness, for when he laid hold of her, his fingers were bruising and her body contracted from the pain.

Thierry started bailing the boat out again as Warrin manoeuvred himself and his burden carefully on to the rope ladder. ‘What about her husband?’ Thierry asked curiously as he worked. ‘He is bound to scour the city for her.’

‘He won’t find her.’ Warrin paused on the ladder to gain his breath. ‘Not until I’m ready, and by then he’ll be glad to die.’

‘I wouldn’t be too sure of that,’ Thierry said. ‘A word of advice: don’t think you’ve won until you’re standing over his body.’

Warrin’s knuckles whitened on the ladder rung. ‘Get you gone,’ he said through his teeth, ‘now, while you still have the chance.’

‘There speaks a man of decision,’ Thierry retorted. Performing a mocking salute at Warrin’s turned back, he sat down and took up the oars.

Warrin puffed a hard breath and completed the journey up the ladder. Stepping over the vessel’s side he took his burden to an aftward awning — a somewhat flimsy affair of oiled canvas and wooden struts, where he threw Heulwen down on a leaky straw mattress at the far side.

Cursing the rain and hoping that it would have emptied its worst and moved on by dawn, Adam squelched into the house and hung his dripping cloak on a clothing pole near the fire. The men-at-arms were organising to bed down for the night, but the rush dips were still kindled against his return and a trestle stood close to the hearth upon which a platter of cold meat and fruit and a pitcher of wine were laid out.

Adam glanced at the repast and then ignored it. The fare at Fulke’s table had been rich and spicy and the wine potent. Although not drunk, he was not entirely sober and had no wish to begin the morrow’s journey with a blinding headache and churning gut.

He left Sweyn and Austin peeling off their sodden garments and went back out into the downpour and up the outer stairs to the floor above. Elswith opened the door to his knock. ‘My lady, thank the Virg—Oh it’s you, Lord Adam!’ The maid wrung her hands and looked at him with a mingling of relief and consternation.

Adam removed his sling, and picking up a towel from beside the small laver began to rub his hair dry. ‘Where’s your mistress?’ He looked round the room. The travelling chests were packed, all save one small one of oxhide for their personal effects, and the room was tidy, almost as bare as a monk’s cell.

‘Lady Heulwen went down to the stables more than a candle notch since with Sir Thierry. He begged her to come quickly, said that Vaillantif was dying!’

Adam’s hands stopped. ‘What?’

Elswith burst into tears. ‘Oh, my lord, she was cross with me, ordered me to stay here and finish packing…I said it wasn’t decent, but she wouldn’t heed me. I didn’t mean to be insolent, truly I didn’t!’

Adam stared at the maid, thoroughly bewildered. ‘What wasn’t decent? What are you babbling about?’ He threw the towel down.

‘My lady was japing. She tried on some of your clothes and said that she was going to travel in them tomorrow — I begged her not to — and then Sir Thierry came and she went with him without even bothering to change.’ She buried her face in her palms and shook her head from side to side.

‘To the stables?’

Elswith peered at him through her fingers and gave a loud, mucus-laden sniff. ‘Yes, my lord, but it has been a long time now…I was wondering whether to go down, but I did not want her shouting at me again.’

Adam began to feel cold, and it was nothing to do with his wet clothing. ‘Stop snivelling and go and tell Sweyn and Jerold not to unarm,’ he said with quiet intensity, and went back out into the rain.

Vaillantif raised his head from the manger. Munching noisily, he stared at Adam with alert liquid eyes. His cream tail swished softly against his hocks and he pricked his ears. In the next stall, the new black mare was dozing slack-hipped, and beside her Heulwen’s dappled grey was asleep. Except for contented, normal horsy sounds there was silence. Adam stared round, eyes wide, ears straining. Nothing. The cold sensation in the pit of his belly crystallised into a solid lump of fear.

He turned to the groom who had emerged from a empty stall in the stable’s far reaches, knuckling his eyes and yawning. A woman’s voice complained, calling him back, and he gave Adam a sheepish grin. ‘Thought I’d have an early night ready for tomorrow, my lord,’ he said to Adam’s set features.

‘Have Lady Heulwen or Thierry been here tonight?’ Adam demanded curtly.

‘No, sire. Not since your mare was settled in. Is there some trouble?’

Adam ignored the query. ‘Has Vaillantif been all right?’

‘Yes sire.’ The groom gave him a gappy grin. ‘Dancing on all fours he were when we brung the mare in. I reckon as she’ll come into season before long.’

‘Saddle him up.’

‘Now, my lord?’ The man’s eyes widened in dismay.

‘No, in three years’ time!’ Adam snarled. ‘Of course I mean now, you idiot! And you can do the same for Sweyn’s and Sir Jerold’s. Be quick about it. You don’t get paid for doing nothing!’

The man’s face became as blank as a dunce’s slate. He tugged his forelock and scuttled off to find the harness. Adam stalked back to the hall.

Thierry’s cousin Alun was all numb astonishment. ‘Thierry? Take Lady Heulwen?’ He shook his head emphatically. ‘I know he has his wild moments but he would not do such a thing, I know he wouldn’t!’

‘And you have no idea of his whereabouts?’ Adam pressed his hand against the doorpost, his knuckes showing bone-white with pressure.

‘My lord, if I did, I swear I would tell you, if only to prove his innocence.’ He shifted his feet and cleared his throat nervously. ‘Perhaps Lady Heulwen had an errand and he went to escort her?’

‘Then why did he need to use the pretence of a sick horse to lure her from the room?’ Adam retorted.

‘Perhaps it was just an excuse for the maid to hear.’

Adam’s hand flashed down to his sword-hilt, then stopped. Carefully, breathing hard, he transferred his grip to his belt and squeezed the leather as though it were a man’s throat.

Alun said, ‘Thierry has a girl at the keep, a kitchen lass called Sylvie. Probably he’s with her. I know there has been a mistake.’

‘So do I,’ Adam said grimly. ‘Sweyn, Austin, come with me. Jerold, take the men and search the streets.’

‘Yes, my lord.’

Adam collected a brand and set off for the back of the dwelling.

‘It’s Warrin de Mortimer, isn’t it?’ grated Sweyn, pacing beside him.

Adam did not answer, but Sweyn received his reply in the rapid increase of Adam’s stride as though he were propelling himself away from the very thought. Passing the stables, Adam slowed his pace to wait for his bodyguard and said, ‘You’ve had more command of Thierry than I have. What do you think of him?’

Sweyn grunted and gave Adam a sideways look. ‘You’ve seen him fight, my lord.’

‘He’s damned fast in a tight corner,’ Austin contributed.

‘Usually of his own making,’ Sweyn growled. ‘Got no moral backbone. He wenches, he drinks and he gambles. Christ’s balls, how he gambles! And then he gets into a fight.’ The old warrior cleared his throat and spat. ‘Alun’s the steadier one, covers up for him when he can. If you recall, when you took them on it was Alun who did most of the talking.’

‘Is he covering up for him?’ The question was half-rhetorical. They reached the edge of the garden. The rain pattered and dripped. Beyond the orchard, unseen but heard, the river lapped at the wharving.

‘No, I’d say not,’ Sweyn said to his master’s silence, ‘but probably he will try to find him and warn him what’s afoot.’

‘Send one of the men to follow his movements and make sure Alun’s given the chance to break away. Austin, take the message back to Jerold.’

Hunching into the collar of his cloak, the youth saluted and left. Adam paused and leaned against one of the trees and said quietly to the older man, ‘Sweyn, if I stopped to think what might be happening to her, you’d be dealing with a madman.’

Sweyn hesitated, then set his huge hand on Adam’s soaking shoulder and gripped it. ‘We’d all go mad if we stopped to think, lad,’ he said gruffly.

Adam acknowledged Sweyn’s attempt at comfort with a stiff nod, and holding the torch aloft, started off again. His right foot came down on something small and hard that made him catch his breath and swear. He thought it was a broken twig, but the torchlight reflected off a shiny surface instead of the matt darkness of bark. Sweyn stooped and picked up a small metal object and gave it silently to Adam.

It was an engraved silver braid fillet, one of a pair that Heulwen had bought that morning in the market, and Adam recognised it immediately since he had made the final choice for her. ‘It is Heulwen’s,’ he said hoarsely to Sweyn. ‘She would not have come down here in this rain unless she had solid reason — or was forced.’

‘The river. ’ Sweyn began, but Adam had already moved off in that direction at a brisk pace.

The merchant’s wharf was deserted. Adam rested his hand on the weed-slippery mooring post and stared out across the dark water at dark nothing. The torch hissed and sputtered and the wind wavered streamers of heat back into his face. ‘The boat isn’t here,’ he said over his shoulder to Sweyn. ‘There was one moored here when we took these lodgings, and it’s gone. It would be the safest means of abduction; no guards to pass.’

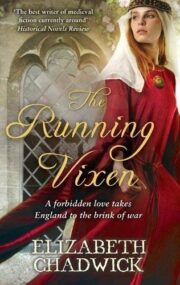

"The Running Vixen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Running Vixen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Running Vixen" друзьям в соцсетях.