Adam set one arm compassionately across Renard’s shoulders. ‘I felt like that the first time too, and the second, and the third. Everyone does, but it is a lesson you have to learn for yourself. No one can tell you.’

Renard’s dark grey eyes went blank. ‘It gets easier then?’ he said through stiff lips.

‘No, but you learn to shut it out; you have to. If you had not killed him, he would have killed you.’ Adam tightened his grip and shook Renard slightly, imparting reassurance. Renard winced and drew a hiss of pain through his teeth, his hand clutching his side. Adam released him, eyes sharpening. ‘You idiot, why didn’t you say you were hurt?’

‘It’s not serious — well at least I don’t think so. Sweyn killed the man before he could put any weight behind his thrust.’ Renard closed his eyes and fought the urge to retch as he saw again the axe cleaving down and the head splicing apart beneath it.

‘Are you fit to climb into a saddle?’ Adam indicated Vaillantif. ‘You’ll have to sit pillion like a wench, but the way this snow’s starting to come down I’d rather reach Thornford before dusk, and the Welsh may well have reinforcements close by. We couldn’t withstand another brawl like this one.’ He mounted up and extended his hand. Renard grimaced through clenched teeth, but hauled himself competently astride, and only when secure did he hang his head and let out his breath in a gasp of pain.

One of the men-at-arms stripped the dun stallion of its harness and loaded it on to the horse bearing the two dead men. The Welsh bodies they left where they had fallen and where they would presently be taken up and borne away by their own people. The snow floated down, covering the land in a white healing blanket, curtaining the horsemen as they rode away, muffling the beat of hooves to silence so that the only sound was the keening of the wind.

Chapter 8

‘Do you believe that I should have approved the match between Heulwen and Warrin?’ Guyon asked his wife.

Judith ceased grooming her hair, put down her comb and turned to her husband. He was sitting before the hearth, looking indolently at ease with a cup of wine in his hand and his feet stretched out resting comfortably against Gwen’s firelit rump, but she had been married to him for too long now to be deceived.

‘What reason could you have had to refuse?’ She rose and came to him. Placing her hand on his shoulder she felt the tension there, and began to work on the knotted muscles. ‘Both of them seem eager for the match. She’s not a child any more, Guy; she’s long been a woman grown.’

He closed his eyes and gave a low-pitched sigh of pleasure at her ministrations, but his mind remained sharp. ‘I know that, love. I also know it hasn’t been easy for you having her here at Ravenstow.’

‘And you wonder if you have given in too easily in the hopes of having a return to peace in your household? ’ she said archly.

‘Most assuredly that is part of it,’ Guyon acknowledged with a laugh, then sobered. ‘I just wonder why Warrin should be so keen to wed her. Men of high estate do not marry for love. Well and good if love grows from a match, but it is not the foremost reason for tying a knot. There have to be others.’

‘Heulwen married for love the first time,’ Judith pointed out.

Guyon snorted. ‘What she thought was love. Moonstruck lust in reality, and I was dotingly led by the nose to arrange a disaster.’

‘Tush, it was a sound business arrangement,’ she objected, leaning round to kiss the corner of his mouth. ‘Ralf ’s skills and our horses. It wasn’t just Heulwen’s pleading that caused you to make the offer.’

‘Perhaps,’ he conceded. ‘But it has given me cause for doubt. Am I doing the right thing this time? Where Heulwen is concerned, I stand too close to see clearly.’

For a time, Judith continued kneading his shoulders in silence while she considered. ‘The blood bond with you and her dowry are reason enough for him to seek her in marriage,’ she said at length. ‘He’s known her for a long time, and he did offer for her before.’

‘Perhaps,’ Guyon said without conviction. ‘But there are other heiresses of similar, if not greater value.’

‘Then mayhap part of her value to him does lie in personal attraction, and that is all to the good. After the way Ralf treated her, Warrin’s pride will be like balm on an open wound.’

Guyon was silent. Judith eyed the back of his neck with exasperation, recognising this mood of old. He would sit on his doubts like a broody hen on a clutch of eggs, and nothing would move him until they either hatched or went stale. How to send them stale? She pursed her lips: after twenty-eight years of marriage, she had several diversions in her armoury — short-term at least. She slid her hands down over his collarbone and chest, leaned round to kiss him again on throat and mouth, let her hair swing down around them, bit him gently.

‘It was snowing on our wedding night, do you remember?’

Guyon’s lids twitched but did not open. He caressed Judith’s hair with a languid hand. ‘Yes, I remember,’ he said, with a smile. ‘You were scared to death.’

She propped her chin on one hand and traced her index finger lightly over his chest. ‘I was too young and badly used to know better,’ she said softly. ‘You gave me the time I needed and for that I’ll always be grateful.’

‘Just grateful?’

‘What do you think?’ She sought teasingly lower and giggled to hear him groan.

‘Jesu, Judith, I’m not young enough to game all night any more!’

‘What would you wager?’

‘Doubtless my life if I made the attempt!’ He laughed, and half lifted his lids to study her. The rich tawny hair was stranded with silver now, and fine lines webbed her eye-corners and spidered around her lips. But she was still attractive, her body trim despite the bearing of five sons and two miscarriages between. Theirs had been a political match, forced upon them both, and begun with mistrust and resentment on both sides; but out of the seeds of potential disaster had grown a deep and abiding love. His pleasure in her was still as keen as it had been in the early days, for Judith had an extensive store of devices and surprises to keep him interested, and he was essentially of a faithful nature, seeing no point in going out to dine on pottage when there was a feast at home.

‘The trouble with Ralf was that he enjoyed pottage,’ he murmured.

‘What?’ Bewildered, Judith stared at him.

‘Nothing. Foolish thoughts aloud. I told you, you’re flogging a dead horse.’ Laughing, he pushed her hand away.

‘Speaking of which, Renard will need another mount before we go to Windsor.’ She kissed his jaw and laid her head on his shoulder. ‘He bids fair to outstrip you in height and he’s not sixteen until Candlemas.’

‘So I’d noticed,’ Guyon said with rueful pride. ‘Starlight can go for use as a remount. There must be at least another five years left in him. He was only a youngster when Miles first had him.’

Judith felt the familiar pang strike her heart as he spoke the name of their eldest son; her firstborn, drowned with his cousin Prince William when the White Ship went down. How long ago was it? Six years, and still as if it were only yesterday she could see Guyon riding into Ravenstow’s bailey with the disastrous news received in Southampton, and she eight months pregnant with William, the wind raw on her face, turning her cheeks as numb as her mind. No grave at which to mourn, just a wide expanse of grey, sullen water.

She nuzzled her cheek against Guyon’s bicep seeking to blot out the pain, and thought of her father the King, whose every hope and scheme had foundered in that vessel. Not only the loss of a son, but the loss of a dynasty in male tail. Miles could never be replaced, but at least she and Guyon had the grace of four surviving sons.

‘I haven’t seen Matilda since she left to become an empress,’ she remarked, thoughts of Henry leading her to thoughts of the small, truculent half-sister whom she had last seen at the age of seven, stamping her foot at Queen Edith and shrieking in a tantrum that she was not going to Germany, that no one could make her.

‘Apparently you are fortunate,’ Guyon said drily. ‘Adam was not impressed.’

‘I feel sorry for her.’ Judith defended Matilda. ‘There cannot have been much joy in her life. A little girl adrift in a strange country, forced into different customs and language, and cut off from her family. I know her husband was kind to her, but to a child of her age he must have seemed ancient.’

‘A replacement for her father then,’ Guyon said sleepily, and yawned.

‘Probably,’ Judith agreed. ‘So when he died, and her real father started making demands on her to come home when it was he who had packed her off in the first place, is it any wonder that she should turn mulish and difficult? After all, he hasn’t recalled her out of loving concern, has he? I’ll wager he rubbed his hands with glee when her poor husband died! She knows very well that if her brother were still alive, or if Queen Adeliza had proved a competent brood mare, she’d still be in Germany, the Dowager Empress and highly respected by people whom she knows and suits. As it is, all the barons are eyeing her with suspicion and muttering into their wine. A mark to a penny there’s another husband being chosen for her, strictly of her father’s choosing.’

She paused to draw breath, aware that her indignation on Matilda’s behalf had carried her too far. Her words, by association, might lead back to the niggling treadmill of the match between Heulwen and Warrin de Mortimer, the very thing she had sought to distract Guyon from in the first place.

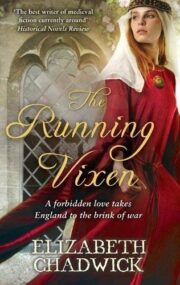

"The Running Vixen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Running Vixen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Running Vixen" друзьям в соцсетях.