Her hands fell from her braids. ‘Adam?’ she repeated weakly. ‘Why does he want to see me?’

Renard gave her a mocking grin, head flung back to avoid the strivings of the pup. ‘Perhaps he wants to arrange another midnight tryst in the solar,’ he suggested.

‘Renard!’ snapped his mother, glaring at him with disfavour. ‘If you spent as much time exercising your brain as you did your tongue, you would have a wit to be feared indeed!’

‘Sorry,’ he said with the graceless joy of one who is not sorry in the least. ‘He’s brought you your horses. You did say you were going to sell them in Windsor, didn’t you? And you’ll have to face him sooner or later.’ He held the pup in the crook of his arm like a baby and wandered over to the sewing trestle to look with idle interest upon his mother’s endeavours.

Judith frowned at him, although she was secretly proud. His height dwarfed hers, although childhood was still stamped on the features of the emerging man. There were crumbs on his upper lip amidst the dark smudge of a soft moustache line. The crimson wool would suit him very well. He was tall like Guyon and dark-haired, but his eyes were the grey impenetrable ones of his grandfather the King. He also possessed his grandfather’s sleight of tongue, married to a lethal adolescent lack of tact. The future lord of Ravenstow and the responsibility, God help her, lay at her feet.

Renard kissed his mother’s cheek and looked across at his half-sister, eyes dancing. ‘Do you want to send me back down with a message and tell him you’re too busy sewing?’

The thought of what Renard might say spurred Heulwen out of one kind of panic and into another. She put the pins carefully aside, resisting the temptation to stick them in her brother instead of his new tunic. ‘No, Renard, that would be a lie, and anyway, I’d be pleased to see him. One misunderstanding does not make for a lifetime’s enmity.’ She widened her eyes sarcastically. ‘What do you imagine happened in the solar? Or perhaps, knowing your mind, I shouldn’t ask. The pup’s just pissed on you.’

‘What?’ Renard looked, swore, dumped the puppy on the floor, and dragged off his tunic to his mother’s stern reprimand about his language. Heulwen made her escape.

It was stupid to be so afraid, she thought as she twisted her way down the turret stairs and entered the great hall. Stupid to feel so tense and queasy. ‘He is my brother,’ she repeated to herself but to no avail. That part of her past was gone for ever, banished by the sight of a lean-muscled warrior in a bathtub. No, she amended, it was not stupid to fear danger or to panic when forced to greet it face to face.

Adam was in the courtyard talking to Eadric, his furred cloak thrown back from his shoulders, the cold sunlight reflecting off his hauberk and the silver pendants studding his swordbelt. The groom had custody of two fine horses — a bay and a piebald. Vaillantif ’s reins were held by Adam himself, and as he spoke to the servant, he caressed the bright sorrel neck, thick now in its full-grown winter fell.

Heulwen took a deep breath, gathered her courage in both hands, and walked across the ward to greet him.

‘You wanted to see me?’ she said to Adam. ‘Will you come within to the hall?’

He hesitated, then inclined his head. Having given Vaillantif ’s bridle to Eadric, he followed Heulwen back across the ward. A woman accosted her with a question about the pigs that were being dissected. While Adam waited, he stared around. A serjeant was drilling his men. The spear butts scraped on gravel and clacked in forested symmetry as their owners responded to bellowed commands. The woman departed with her instructions. Against the forebuilding entrance, two small boys were playing marbles. One of them raised his head and flashed a brilliant blue-green glance at his sister and the visitor.

‘Why aren’t you at your lessons?’ Heulwen demanded sharply. ‘Where’s Brother Alred?’

‘Gone into the town with Papa.’ William made a face. ‘We’ve to do our lessons this afternoon.’ His gaze lit covetously on Adam’s ornate gilded scabbard and the contrastingly austere sword-hilt protruding from it.

Heulwen said to Adam, ‘William wasn’t here last time you visited.’ She turned to the boy: ‘William, this is Adam de Lacey, my foster brother. I don’t think that you’ll remember him.’

Adam crouched down and picked up one of the round, smooth stones, his expression carefully impassive, aware that she had said ‘foster brother’ deliberately.

‘Can I look at your sword?’ William’s eyes were avid with longing. Belatedly he remembered to add ‘please’.

Adam shot the marble at a larger one near the wall. He heard the crack of stone upon stone and briefly closed his eyes, fists clenched upon his knees. Then he stood up and, smiling down at the boy, drew the weapon from its fleece-lined scabbard.

‘William, you shouldn’t be so. ’

‘He’s all right.’ Adam’s voice was relaxed, concealing the tension that gripped him. ‘I was the same at his age about your father’s blade — about any blade come to that, because they were real and mine was made of wood, or whalebone.’

William took it reverently. His small fist closed around the leather-bound grip and he held it up to the light so that the iron gleamed bluishly. Inlaid along the blade in latten was the Latin inscription O Sancta, repeated several times to make a decorative pattern. The pommel was an irregular semicircle of inlaid polished beechwood. ‘Papa says I can have a proper sword of my own next year day,’ William said eagerly.

‘With a proper blunt blade,’ Heulwen added. ‘You do enough damage with the plain wooden one you’ve got now!’

Adam chuckled. ‘I can imagine!’ Gently, with more than a hint of poignant understanding, he took the sword back from the child, slotted it home, tousled the tumbled black curls, and continued with Heulwen into the keep.

She sent a servant to fetch hot wine and offered him a chair on the dais set close to a brazier. He unfastened his cloak and draped it across the trestle; unlatching his scabbard, he placed it on top.

‘Do you want to unarm?’ Heulwen indicated his hauberk as he stretched out his legs to the warmth.

He shook his head. ‘Thank you, but no, it’s only a passing visit, I won’t keep you long.’

Heulwen looked down, wanting to apologise for the way their last encounter had ended but unsure that a reconciliation was in her own best interests. White-hot physical attraction frightened her. She had sat at its blaze before, watched it go out, and shivered over the ashes.

The servant brought the wine and a dish of the cinnamon apple pasties, and returned to his duties. Across the hall at another trestle, Adam’s men sat around a basket of loaves, bowls of salted curd-cheese, and flagons of cider. Watching them Adam said, ‘I’ve returned Ralf ’s stallions so you can decide whether you want to sell them at Windsor.’

Heulwen poured wine for them both, keeping her eyes on her task. ‘What are they worth? Have you had time to find out?’

‘The bay is almost fully trained and sufficiently well bred to fetch you around forty marks,’ he said, his tone brisk and professional. ‘The piebald’s not of the same calibre, but because of his markings you should get around twenty for him. If I continue to school him over the winter, he could fetch a top price of twenty-five.’

‘And Vaillantif?’ she matched his tone.

‘That’s really why I came.’ He transferred his gaze from contemplation of his men and fixed it on her instead. ‘I want to buy him from you, Heulwen. I’ll give you a hundred marks.’

She forgot her circumspection and stared at him in astonishment. ‘How much?’ she gasped

‘It is what he is worth.’ His eyes were bright and intense as he leaned forward in the chair.

‘Adam, no, I cannot accept such a sum from you!’

‘But you would accept it from a complete stranger at Windsor,’ he pointed out.

‘I wouldn’t feel guilty about taking a stranger’s coin.’

He set his jaw. ‘Heulwen, I’m asking you as a boon — as a favour to me. Let me have him. You’ve slapped me in the face once. In Christ’s name, leave me some small shred of pride. Do you know what it cost me to come here today?’

She opened her mouth to speak, changed her mind and drank her wine instead. ‘Yes, I do know,’ she said after a swallow. ‘The same that it cost me to come down from the bower to face you.’

Adam considered her across his own cup and eventually he smiled. ‘Pax? ’ he said gravely.

‘Vobiscum.’ She returned the smile, feeling as though a great dark cloud had been lifted from her horizon. ‘Very well. For the sake of our mutual pride, you can have Vaillantif, but I won’t accept the full price — and before you start arguing, let me say that I owe you for the training and stabling of the other two horses. Eighty marks I’ll take for him, not a penny more.’

‘And if Warrin thinks that you have undersold a part of his future property?’ he asked with an edge to his voice.

‘Then Warrin can go whistle. I’m not. ’ Her voice trailed off and she put her hand to her mouth.

‘What’s wr—’ Adam followed her gaze down the hall and saw, as if conjured from thought, Warrin de Mortimer advancing towards them in the all too solid flesh, his cloak bannering behind him with the vigour of his stride and his brows slanted down in a black scowl.

‘Adam, I will kill you myself if you start anything,’ Heulwen hissed from the side of her mouth, as she rose and prepared to greet her husband designate.

‘Me?’ he said sarcastically. ‘Why should I want to start anything? Do you think I want to be on your conscience for the rest of your life?’

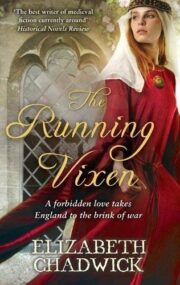

"The Running Vixen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Running Vixen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Running Vixen" друзьям в соцсетях.