What did she see that made her lower her eyes? I felt as if the ceiling were coming down on me. “Tell me.” I grabbed her by the arm, pulled her so she had to face me.

Her eyes looked wild, as if she were in a snare, cornered and fighting for a way out. “The strong must suffer everything, everything! Don’t you understand?” She struggled to break free of my grip, but though she may have been a prophetess she wasn’t much of a wrestler. “I can’t be upset. Let me go! Ukashin!” she called out. Her voice was shrill enough to carry downstairs. “Taras! Andrei!”

“Don’t scream, please.” I let her go, holding both hands up in surrender. “For God’s sake, Mother.”

She only became more agitated. “Ukashin!”

I had to stop her screaming. I couldn’t believe my own mother was afraid of me. It was a nightmare. “Please, I’m not hurting you!” I reached out, but she shrieked again before I could touch her, shrinking from me as though I held a hot torch, a live viper. “Ukashin!”

“I’ll stay away,” I said, backing up until I hit something that clattered—her vanity table. “I’m way over here.” Please, Seryozha, help me. You were always her favorite. Come and deal with this. I was never good with her.

The door opened and light from the hall fell across the carpet. The Master staggered in, stinking of sweat and wine. How huge he looked outlined against the light from the hall, like a genie released from a bottle, filling the doorway. “What’s going on in here?”

My mother cringed before her icons. “She’s been tormenting me.”

He lowered his great bull’s head as if he would charge me. “I see.”

“I just wanted to talk to her.” I still clutched that clear piece of tumbled quartz.

“Forgive us, Mother.” He crossed the room and yanked me out by the arm, shoved me into the hall, and closed off the Mother’s world behind us.

I stood in the hallway holding my wrenched shoulder, hot tears shamelessly streaming, gulping air that hadn’t been stained with that acrid smoke. I wished to God I had never opened that door. I’d been operating under the illusion that I was special, that I could walk a tightrope between worlds, a privileged character, the Daughter. But I was not special in any way. No father, no mother… now I was truly here, fully in the hands of this cosmic bully and his mad priestess. There would be no other future.

79 Andrei Ionian

MY PUNISHMENT WAS TAILOR-MADE to fit the crime. The night after my transgression, the Master stopped me in the hall. “Andrei needs to learn about hunting. Take him with you in the morning.” And turned away. There would be no argument. How appropriate to consign me to Andrei Ionian, depriving me of the one thing I needed after that encounter with my mother: solitude. I needed time to think, to make some plans. Now I would have the professor dogging my days with his steady stream of philosophy and gangly obliviousness.

The following morning, I got him onto a pair of homemade skis, and soon we left the house behind, smoke trickling from its chimneys, the dark wood of the outbuildings slowly diminishing to train-set size, like toys dusted in soap flakes. I needed to sort out my thoughts about my place at Ionia, my responsibility to the baby, and the way Mother had looked at me like someone examining a stamp through a magnifying glass. The way she’d shrieked for Ukashin. But Andrei could not be still. The very air around him crackled with anxiety. For someone who extolled the virtues of the present moment, could Andrei be any less present?

He launched into a lecture about his favorite subject, simultaneous incarnation, the proposition that we live many lives at once in parallel streams of space-time. This was what my mother had been talking about—seeing Seryozha at four, Seryozha as an old man, a soldier, a dog, a dancing master. I only wished it were true. Then I might be back before the revolution, living with my child and my clever husband, hosting Wednesday at-homes in turban and pantaloons, smoking a little cigar and writing my decadent poetry, instead of stranded in this mystical commune, trapping small animals in the bitter cold. But Andrei wasn’t content with imagining it: he wanted it to literally be so. Mathematically provable.

Well, who was I to criticize? My job was to show him hunting, and that’s what I would do. I pulled my scarf over my nose and mouth and kept moving.

“You see, it’s all our perspective.” It was the Ionian catechism—things that appeared separated on the third dimension were simultaneous when seen from the fourth, more so from the fifth, and so on. He panted to keep up with me, his breath a plume of vapor, but the flow of information never stopped. “You have to look at the position which encompasses the highest point of view.”

He was so desperate that I understand. I saw that for an intellectual like him, the need to be understood was a trap. Once caught, he just kept tightening the noose around himself. He would be better off just admiring the beauty of his system for his own sake. I couldn’t help wondering, what was my own trap? Reflexive hope? The yearning for peace? No, those held no allure. Passion. And the need to see what happened. One’s strength, overdone, was one’s weakness.

As I waited for him to catch his breath—a painful sight, hands on his knees, gasping—it occurred to me that this reassignment must be Andrei’s punishment as well as mine. But what had been his crime? Not keeping me from Mother’s room? On the icy, misted air, I could hear the rooster bragging how he’d made the sun rise. I hiked on, trying to get away from the tide of nervous chatter, which resumed as soon as he could speak.

I stopped on top of a rise, alone for a short moment. Overhead in an ancient apple tree, ravens cawed and clicked their strange squirrel sounds and dropped twigs on my head. I no longer saw them as harbingers of doom, but welcomed them as clever companions whose language I could almost decipher. I stroked the apple tree’s trunk, its spiraled bark like a shirt wrung out by a beefy washerwoman. Its deformation probably had saved it from many a woodsman’s ax. It looked like a claw, an old man’s hand. What do you have to tell me, Tree?

Endure, it said.

I used to ride here with Volodya, the two of us on his bad-tempered pony. He’d put me in front and let me hold the reins, tall grass brushing our bare feet. We’d stop to let Carlyle eat the fallen apples, the fruit small and hard. In those days when you looked back at the house, you would always hear music, Mother playing her piano, Olya singing while she hung the wash in the summer sun.

Now all that was gone. Just me and the tiny passenger. What kind of a life was I facing? What did Mother mean, the strong must suffer everything?

Andrei finally managed the hill, his skis splayed in a gawky V. His scarf, tied across his nose and mouth, had grown thick with frost. But still he talked on, about the folds of space-time: “So you’re you now, but also you at eight walking with your mother, going to fetch some sweets. And eighty, leaning on your daughter’s arm.”

“But we still have to live here and now,” I said. “I don’t see why this is so important to you.”

“It’s essential. Vital! If we could figure out the mathematics of the parallel streams, we would be seen as magicians. Time travel, jumping between alternate lives would become a reality. Seeing the intention of the entire structure. That’s what we should be studying, not whirling around with our eyes closed.” He took out a handkerchief and blew his nose vigorously. The crows cawed in response.

But I liked the whirling. Opening the vortex, we called it. It was my favorite thing at Ionia. It made you less hungry, more peaceful, and the room held that beautiful energy. We got along better afterward. “What about the sacred spiral? I would have thought you’d approve.”

“We should be examining the layers of existence. It’s a different order of magnitude.”

“But it’s right out of that book you gave me, The Structure of Reality.” The spiral was the gateway to higher dimensions. What could he object to in its embodiment?

“You’re dancing it. It’s not the same as engaging here.” He knocked on his forehead. “You can draw a motor, too, but it won’t take you to Moscow.” He sighed, whacked a tree trunk with a crude ski pole. “But nobody cares. It’s too much mental work. I’ve failed here if you can’t see how it matters.” I could see I’d offended him.

We started down the hill toward the aspen copse, the trees all talking to each other, their roots entwined. “I wrote a poem about parallel time streams,” I said. He seemed so bitter that no one cared about his cosmic theories, I thought it might cheer him. “Want to hear it?”

“Go on.”

On the pond,

a girl

etches figures in the ice.

Redheaded as an oriole

She poses, arabesque.

Across the park,

a woman

stands on a fourth floor window ledge,

Caught between freedom and despair

Her falling hat frees crimson hair

Passing below,

the crone

seems to recall some still-life story

of her own, but when?

She catches the hat,

Midair.

It’s just her size.

Racing ahead,

the flameheaded tot

giggles, naughtily.

Glancing back at Gran,

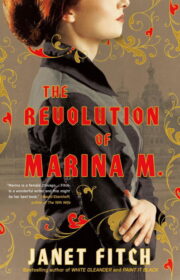

"The Revolution of Marina M." отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Revolution of Marina M.". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Revolution of Marina M." друзьям в соцсетях.