He dare not delay. There were too many waiting to snatch his lands from him. He could not conquer the whole of Ireland as he had planned. Roderick of Connaught would have to wait.

Leaving Hugh de Lacy behind with a garrison to hold what he had gained he sent messengers to the Cardinals telling them that he was sailing at once for England and would in due course arrive in Normandy.

That Christmas the young King Henry decided to remind everyone at his Court that he was indeed their King. His father had sent him to Normandy when he went to Ireland, where he was to act as a kind of regent. ‘A regent,’ stormed Henry to William the Marshall, ‘why should I be a regent? I am a king in my own right.’

William the Marshall, the Earl of Salisbury’s nephew, who had held a post of knight-at-arms to young Henry for some years, was his closest friend and companion. ‘In due course you will be so in every way,’ he reminded him.

‘Not while my father lives, William.’

‘My lord,’ answered William, ‘it is unwise to mention the King’s death.’

‘How can I help mentioning it? It can only be when it happens that I shall be free.’

William the Marshall looked over his shoulder fearfully but Henry burst into laughter.

‘Have no fear. The people here are my friends.’

‘A king never knows who are his friends.’

‘I know that there is not a king in Christendom who has more enemies than my father. His nature is such to arouse enmity.’

‘I would venture to contradict you, my lord.’

‘Have a care, William. Remember I am your King.’

‘And you are my friend also. If I must flatter you as so many do I should cease to be that. What do you wish, my lord, my flattery or my friendship?’

‘You know, William.’

‘I think I do, so I will risk saying that if all men do not love your father there are few who do not respect and fear him; and sometimes it is better to be respected and feared than loved.’

‘The old man has bemused you with his rages.’

‘I beg of you, do not speak of him thus. He is your father and our King.’

‘I am not likely to forget that. But know this, William, he shall not keep me in this state for ever.’

‘My lord, you are young yet. You have won men’s hearts by your nature but you could not afford to stand out against your father.’

‘I did not say I would do that, William. I merely say that I want to be a king in more than name.’

‘But there is already a King of England.’

Henry sighed. ‘Come, let us think of other things. This is my first Christmas as King and I intend to celebrate it as such. This Court shall have no doubt about my rank.’

‘This Court, my lord, knows exactly your rank. You are its King, and it is the first time in England’s history that she has had two Kings.’

‘It was my father’s wish that it should be so, and he can have no one to blame but himself for it. Come, I am determined that my first Christmas as King shall be remembered for ever, so that people will know how merry life will be when there is only one king in England. And I will tell you something, my friend, when I am King and have a son, a crown shall not be put on his head until I am dead.’

William the Marshall was silent, but he wondered, as many had begun to, how Henry II could have made such a major blunder as to have his son crowned King while he still lived.

‘I have it,’ cried young Henry. ‘I shall invite all the knights, counts and nobles together with men of the church to my banquet. They shall have gifts which will prove to them that I shall be a generous king. My father is the most parsimonious man alive. He hates giving anything away. He will never relinquish his hold on one castle while he lives. I will show my subjects here how different I shall be. I want to be as different from my father as I can possibly be. I regret that I share his name.’

‘Would you rather have been a William?’

‘That was my eldest brother. There are more Williams in England and Normandy than any other name, I’ll swear. They are all named after my great-great-grandfather, William the Conqueror. You are one of them, my friend.’

‘I’d say there are as many Henrys.’

‘Nay, William, I’d wager it. I have an idea. At my banquet I shall reparate all the Williams and they shall dine with me in one room. No one who is not a William shall sit down with me. Then you and I will count them and see how many Williams are there. I’ll wager there will be more than a hundred.’

Henry was excited at the prospect and William joined in his enthusiasm, realising that in planning his Christmas celebrations Henry forgot his enmity towards his father.

He was delighted to discover that there were one hundred and ten knights named William and many of other ranks.

He was the only Henry among the Williams who crowded into his chamber. This was called the feast of the Williams.

When his father heard what had happened, he was displeased by what seemed to him childish frivolity. He also heard rumours of his son’s growing dissatisfaction with his state and this was more disturbing than his irresponsibility.

Young Henry left for England soon after Christmas. That banquet had been a great success. It was all very well for his friend William the Marshall to tell him to beware of flatterers. He was popular, good-looking, charming – all things that his father was not, and what William called flattery was in fact the truth.

When he had been at Bures his mother’s uncle, Ralph de Faye, had come to see him bringing with him his friend, Hugh de St Maure, and they had said what accounts they would take back to his mother of his kingly ways.

He had been enchanted by this kinsman and his friend. They had declared themselves quite shocked by the manner in which his father tried to treat him.

‘You might be a child of ten years old by the way the King behaves towards you,’ they said. ‘Why, you are in your seventeenth year. You are a man.’

It was true; he was a man and treated like a boy!

‘You should make your dissatisfaction known,’ Ralph told him.

He knew he should. But how? It was all very well to talk about defying his father when he was not there and quite a different matter when one was confronted by him. Young Henry remembered how the face could flush, the eyes seem to start out of their sockets and the terrible fury begin to rise. Any wise man kept away from that.

Still, they were right. Something should be done, but it would have to be more subtle than confrontation with his father and a demand that he be given his rights.

In the meantime he was going to England and that was where he liked best to be because in England he was a king; and when his father was absent he could delude himself into thinking that he ruled the land.

He was not allowed to delude himself for long. He had not been at Westminster more than a month or so when his father arrived.

Face to face with the older Henry the younger lost his courage. It had always been so. Much as he might rage against him to his friends, his father only had to appear and he was immediately subdued.

‘I hear,’ said the King, ‘that you passed a merry Christmas at Bures.’

‘I think my … our subjects were pleased by the display I gave.’

The elder Henry nodded slowly.

‘You seem to have a fondness for my Norman subjects. That is well because we are leaving shortly for Normandy.’

‘We …’ stammered young Henry.

‘I said we, by which I mean you and I.’

‘You will need me to stay in England while you are in Normandy.’

‘My justiciary Richard de Luci has my complete trust.’

‘Father, I would rather stay here. I have had my fill of Normandy.’

The King raised his eyebrows and his son was alarmed to see the familiar tightening of the lips and flash of eyes which warned any who beheld it that they must be wary, for those were the danger signals.

‘I thought you would wish me …’ began young Henry.

‘I have told you what I wish. You will be ready to leave for Normandy. I desire your company there, my son.’

‘Yes, my lord,’ said the young King quietly.

This was humiliating. Henry secretly raged against the Pope. He had to keep himself under control. He was in a very tricky position. That he, Henry Plantagenet, should be summoned to meet the papal legates was insulting. Yet what could he do? He must act very carefully or the whole world would be against him.

He would have to deal very subtly with those emissaries of the Pope and he wanted to be completely free of anxieties while he did so. Ireland was safe, he believed, even though it was not yet fully conquered. He himself would be in Normandy. Eleanor was in Aquitaine; and he was certainly not going to leave young Henry in England. He would have to be watchful of that young man. He was beginning to see what a great mistake he had made in crowning him King. Why had he done it? To spite Thomas à Becket. To have the boy crowned by Roger of York. Yes, it had been done partly to humiliate Thomas à Becket. Thomas … it always came back to Thomas!

Now he needed some comfort before he left for Normandy and he would go to Rosamund.

He thought there seemed something lacking in her pleasure. She was as deferential as ever, as determined to please and yet there was a certain sadness about her.

He awoke in the night and felt the weight of his trials heavy upon him. He stroked her hair and kissed her into wakefulness.

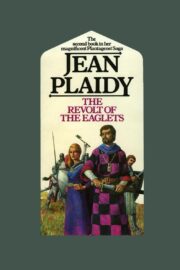

"The Revolt of the Eaglets" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Revolt of the Eaglets". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Revolt of the Eaglets" друзьям в соцсетях.