When she had heard that Thomas had been killed she could not get those words out of her mind. And she kept seeing Henry on those occasions when he had given vent to his rage against the Archbishop. Then he had frightened her with the violence of his fury and only her loving solicitude had prevented his giving way to it. She soothed him at such times by agreeing with him, offering him sympathy, making him realise that whatever he said, whatever he did, she believed him to be right.

And now … Becket.

She could not stop thinking of him. She had heard what had happened at the Cathedral after the death. How pilgrims were already visiting the place, the sick and maimed. They believed that if they kissed the stones on which his blood had been shed they would be blessed and perhaps cured of their sins.

For once she could not say to herself or to the King: You were right in what you did.

Thomas à Becket was between them.

He sensed the change in her. It frustrated him, put a barrier between them. She smiled and was as gracious and loving as ever; he was as ardent; but something had changed in their relationship and they were both aware of it.

There was not the same comfort with Rosamund as there had been.

In the palace at Westminster he visited the nursery. There were only the two youngest of his children there at this time – Joanna in her seventh year and John in his sixth. The fact that he had just made a marriage contract for his youngest son had awakened his interest in him and he wanted to tell the little fellow about his good fortune.

When he strode into the nursery a hushed awe fell upon the place; the nurses and attendants curtsied to the floor and the children watched in wonder. Henry cast a quick glance over the females – a habit which never left him – to see if any of them were worthy of his passing attention; and perhaps because his mind was busy with the change in Rosamund, or perhaps because he was not greatly impressed by any of them, he dismissed them.

The children were looking at a picture book and with them was a girl of some eleven or twelve years. They all rose. The two girls curtsied and young John bowed.

What a pleasant trio. The King felt his mood changing as he surveyed them. His son John was a pretty creature and so was his daughter. In grace and beauty though he had to admit that their companion surpassed them.

He remembered suddenly who she was. Of course she was Alice, daughter of the King of France, and she was being brought up here because she was betrothed to his son Richard.

‘I trust you are pleased to see me,’ said the King.

John smiled; Joanna looked alarmed but Alice replied: ‘It gives us great pleasure, my lord.’

He laid his hand on her soft curling hair.

‘And do you know who I am, little one?’

‘You are the King,’ she answered.

‘Our father,’ added John.

‘You are right,’ said Henry. ‘I have come to see how you are all getting on in your nursery. Come, Joanna, it is time for you to speak.’

‘We get on well, my lord,’ murmured the little girl shyly.

He picked her up and kissed her. Children were charming. Then he picked up John and did the same. When he set him down he looked at Alice. She blushed slightly. ‘And you, my lady,’ he said, ‘I must offer you like treatment, must I not?’

He lifted her in his arms. Her face was close to his. The texture of children’s skin was so fine, so soft. Even beauties like Rosamund could not compare with them. It gave him great pleasure to hold this beautiful child in his arms. He kissed her soft cheek, but he did not put her down. He went on holding her. He looked into her eyes so beautifully set. Richard, he thought, you have a prize in this one. The idea of monk-like Louis siring such a perfect little creature amused him.

John and Joanna were looking up at him. He held Alice against him and kissed her again, this time on the mouth.

‘You kiss Alice more than you kiss us,’ said John.

Henry put the girl down. ‘Well, she is our guest so we must make sure she knows she is welcome.’

‘Is Alice our guest then?’ asked John. ‘They say she is our sister.’

‘She is to be your sister and she is our guest.’ He took one of her ringlets and curled it round his finger. ‘And I want her to know that there was never a more welcome one in my kingdom. What say you to that, little Alice?’

She said: ‘My lord is good.’

He knelt down, feigning to hear her better, but in fact to put his face closer to her own.

‘I like you well,’ he said; and he patted her face and his hands went to her shoulders and moved over her childish unformed body.

He stood up.

‘Now I will sit down and you shall tell me how you progress in your lessons.’ He looked at John whose expression had become a little woebegone.

‘Well, well, my son,’ he said, for his spirits were higher than they had been since he had heard of Becket’s death, ‘we’ll not go too far into the subject if it is not a pleasant one, for this is an occasion for rejoicing.’

He took Alice’s hand in one of his and Joanna’s in the other and led the way to the window. He seated himself there. John leaned against one knee and Joanna against the other. ‘Come, Alice, my dear child,’ he said, and drawing her between his knees held her close to him. ‘Now,’ he said, ‘we are a friendly party. John, my son, I have come to see you because I have some good news for you.’

‘For me, my lord,’ cried John starting to leap up and down.

‘You must not do that,’ said Joanna.

‘Oh, we will let him express a little joy, daughter,’ said the King, ‘for it is a most joyful matter. I have a bride for him.’

‘A bride,’ said John. ‘What is that?’

‘He is too young to understand,’ said Alice.

‘Of course,’ said the King tenderly stroking her arm. ‘But you are not, my little one. You have been betrothed have you not … to my son Richard?’

‘Yes, my lord,’ said Alice.

‘You are too young as yet to go to him,’ went on the King and was amazed at the relief he felt. It would be unendurable to allow this beautiful child to go to some bumbling boy. Richard of course was handsome, but he was too young yet.

‘It will be soon though,’ said Alice.

‘No,’ said the King firmly. ‘There is some time yet.’

‘What about me?’ said John.

‘Listen to our young bridegroom. Joanna, Alice, my dears, listen to him!’

‘You said it was my bride, Father.’

‘So it is, my son. I have found you a bride who will bring much good to you and us, and her father and I have agreed that when you are old enough you shall be married. Her name is … why, she has the prettiest name in the world. What do you think it is? Alice! The same as my dear daughter here. Alice, I have already grown to love that name.’

She smiled delightedly. A little dimple appeared in her cheek when she did so.

‘You are a dear child,’ he said, ‘and I love you.’ He held her tightly against him and kissed her warmly on the cheek.

John was asking impatient questions. How big was his bride? Could she play games? Was she pretty? Was she good at her lessons?

‘She is all these things,’ said the King, ‘and she is very happy to be my daughter and your wife.’

John laughed delightedly. He was a charming little fellow, his youngest son. The others had always resented him in some way. That was their mother’s influence, he was sure. It was very different in the nursery now. He must visit it more often.

Of course his illegitimate son Geoffrey was no longer there. He was being tutored in knighthood. A fine boy, Geoffrey. He had always preferred him to Eleanor’s brood. But his son Henry was so handsome that he would have liked there to be a closer bond between them. As for Richard he was so much his mother’s boy that it seemed they could never feel anything but enmity for each other.

John was different – the youngest child whose love for his father had never been tainted by his mother’s venom.

From now on John would be a favourite of his. He would visit the nursery frequently, and it would not be a duty but a real pleasure. The main reason was that enchanting little creature Alice. A little beauty in the making if he knew anything and from the experience he had had he should know a good deal.

Dear sweet creature, what good she had done him. She had stopped him thinking of the changed attitude of Rosamund and chief of all the murder of Thomas à Becket.

He would be ready to sail for Ireland in August. So far he had kept the papal legates at bay. They would not let the matter rest there, he knew. What would they want of him? Some sort of penance he supposed and if he refused to make it – excommunication. It was not good for a King to suffer that. His subjects were superstitious and if they feared that the hand of God was against him they would turn from him and even those who remained loyal would lose heart. He believed that when men went into battle they must be well equipped for the fight, not only materially but spiritually. They must believe in victory if they were to achieve it. This had been one of the firm beliefs of his great-grandfather, William the Conqueror, who insisted on seeing good in omens when other men feared they might be evil. I only believe in omens when they are good ones, his grandfather, Henry I, had said; and he had proved himself to be one of the most astute rulers ever known.

Therefore he wanted no excommunication. But time was a good ally. The longer the delay between the murder and the bringing home of the guilt the better. Passions cooled and as long as there were not too many miracles at the shrine of Canterbury, he could weather this storm as he had so many others.

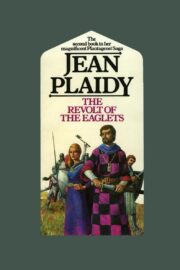

"The Revolt of the Eaglets" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Revolt of the Eaglets". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Revolt of the Eaglets" друзьям в соцсетях.