‘My Henry was angry over Bertrand de Born,’ said Matilda. ‘He wrote love poems to me. Henry discovered and banished him from the Court.’

‘He is a great poet,’ said Eleanor. ‘He is compared with Bernard de Ventadour. I would not have his verses sung in Salisbury though, because he did much to harm your brother Richard.’

‘You know why. He fell in love with my brother Henry.’

‘I thought he was in love with you?’

‘He made verses to me but it was Henry whom he loved. If you had seen the verses he wrote to Henry you would have realised how much he loved him. He thought my brother the most beautiful creature he had ever seen and you know how these poets worship beauty. When my father had taken his castle and he stood before him, his prisoner, my father goaded him with this much flaunted cleverness and asked him what had happened to his wit now. Do you know what he replied. “The day your valiant son died I lost consciousness, wits and direction.”’

‘At which your father laughed him to scorn I doubt not.’

‘Nay, Mother, so deeply moved was he, that he restored his castle to him.’

‘He can be sentimental still about his sons,’ mused Eleanor.

‘He loved Henry dearly. Henry was always his favourite. Again and again Henry played him false and every time he forgave him and wanted to start again. He wanted Henry to love him. His death was a great blow to him.’

Eleanor played the lute and Matilda sang some of the songs which had come to Normandy from the Court of France and Aquitaine. They told of the conflict between the King’s sons and the love of knights for their ladies.

In due course Matilda’s child was born. The confinement was easy and the little boy was called William.

Eleanor, who loved little babies, delighted in caring for him.

Christmas was approaching.

To Eleanor’s amazement and secret delight, a message from the King arrived. He was summoning his sons to Westminster and he invited his wife to join them there. Matilda with her husband and children would accompany the Queen and it should be a family reunion.

The grey mists hung over Westminster on that November day, and in the palace there was an air of expectancy. This was an occasion which would be remembered by all concerned for as long as they lived. The King, the Queen and their sons would be together there.

When Eleanor came riding into the capital the people watched her in silence. This Queen had been a captive for ten years. She amazed them as she had in the days of her youth. There was something about her which could attract all eyes even now. She was an old woman but she was a beautiful one still; and the years had not robbed her of her voluptuous charm. In her gown of scarlet lined with miniver, adjusted to her special taste and with that unique talent which had stylised all her clothes, she looked magnificent.

The watchers were overawed.

Then came the King – so different from his Queen, yet, though he lacked her elegance there was about him a dignity which must impress all who beheld him. His cloak might be short and worn askew, his hair was greying and combed to hide the baldness, although by his garments he might be mistaken for a man of little significance, his bearing and demeanour proclaimed him the King.

She was waiting for him and they studied each other for some moments in silence.

By God’s eyes, he thought, she is a beautiful woman still. How well she hides her age!

The years have buffeted him, she thought gleefully. Why, Henry, you are an old man now. Where is the golden youth who took my fancy? How grey your hair is and no amount of dressing it can hide the fact that it is thinning. Does your temper still flare up? Do you suffer the same rages? Do you lie on the floor and kick the table legs? Do you bite the rushes? But what was the point in mocking? She knew that he was still the King and that men trembled before him.

He bowed to her and she inclined her head.

‘Welcome to Westminster,’ he said.

‘I thank you for your welcome and for the gifts you sent to me.’

‘It is long since we have met,’ he said. ‘Now let it be in amity.’

‘As you wish. You, my lord, now decide in what mood we meet.’

‘There must be a show of friendship between us,’ said the King. He turned away. ‘Grief has brought us together.’

They stood looking at each other and then the memory of Henry, their dead son, seemed too much for either of them to bear.

The King lowered his eyes and she saw the sadness of his face. He said: ‘Eleanor, our son …’

‘He is dead,’ she said. ‘My beautiful son is dead.’

‘My son too, Eleanor. Our son.’

She held out her hand and he took it and suddenly it was as though the years were swept away and they were lovers again as they had been at the time of Henry’s birth.

‘He was such a lovely boy,’ she said.

‘I never saw one more handsome.’

‘I cannot believe he has gone.’

‘My son, my son,’ mourned Henry. ‘For long he fought against me, but I always loved him.’

She might have said: If you had loved him you would have given him what he most wanted. He asked for lands to govern. You could have given him Normandy … or England … whichever you preferred. But no, you must keep your hands on everything. You would give nothing away. Even as she reproached him she knew she must be fair. How right he was not to have given power to the fair feckless youth.

‘We loved him, both of us,’ she said. ‘He was our son. We must pray for him, Henry. Together we must pray for him.’

‘None understands my grief,’ he said.

‘I understand it because I share it.’

They looked at each other and he lifted her hand to his lips and kissed it.

Their grief had indeed brought them together.

But not for long. They were enemies, natural enemies. Both knew the bonds must loosen. They could not go on mourning for ever for their dead son. It was not for mourning that Henry had allowed her to come. She quickly realised that. He had not released her from her prison because he wished to show some regard for her, because he had repented his harshness towards her. No, he had his motive as Henry always would.

He had brought her here for varying reasons that did not concern her comfort or well being.

In the first place she had heard through Richard that Sancho of Navarre had requested it and he wished to be on good terms with Navarre. The main reason, though, was that Henry’s death had made the reshuffle of the royal heritage necessary and he needed her acquiescence on certain points, mainly of course the re-allocation of Aquitaine.

She was overjoyed when Richard arrived at Westminster. Her eyes glowed with pride at the sight of this tall man who had the look of a hero.

They embraced each other and Richard’s eyes glowed with a tenderness rare in him.

‘Oh, my beloved son!’ cried Eleanor. ‘How long the years have been!’

‘I have thought of you constantly,’ Richard told her, and because she knew her son so well she could believe him. Her dear bold honest Richard who did not dissemble as the rest of her family did. Richard on whom she could rely; whose love and trust in her matched hers for him.

‘We must talk alone,’ she whispered to him.

‘I will see that we do,’ he replied.

He came to her bedchamber and she felt young again as she had when he was but a child and she had loved him so dearly and beyond her other children, as she still did.

‘You know why your father has brought me here?’

He nodded. ‘He wants to take Aquitaine from me and give it to John.’

‘You are the heir to the throne of England now, Richard, England, Normandy and Anjou.’

‘He has said nothing of making me his heir.’

‘There is no need for that. You are the eldest now and the rightful heir. Even he cannot go against the law.’

‘He is capable of anything.’

‘Not of this. It would never be permitted. It would plunge the country into war.’

‘He is not averse to war.’

‘You do not know him. He has always deplored war. He hates wasting the money it demands. Have you not seen that if there is a chance to evade war he will evade it? He likes to win by deceit and cunning. He has done it again and again. That, my son, is what is known as being a great king.’

‘I would never stoop to it. I would win by the sword.’

‘You are a born fighter, Richard. A man of honesty. There could not be one more unlike your father. Perhaps that is why I love you.’

‘What think you of him? He has aged, has he not?’

‘Yes, he has aged. But I remember him as a young man … a boy almost when I married him … not twenty. He was never handsome as you and Henry and Geoffrey … and even John.’

‘We get our handsome looks from you, Mother.’

‘’Tis true. Although your grandfather of Anjou was reckoned to be one of the most handsome men of his day. Geoffrey the Fair they called him.’ She smiled reminiscently. ‘I knew him well … for a time very well. A man of great charm and good looks but no great strength. Not like his son. But what has your father become now? An old man … a stout old man. He always tended to put on weight. That was why he would take his meals standing and in such a manner as to suggest he did so out of necessity rather than pleasure. Of course that unrestrained vitality of his kept down his corpulence in his youth but it was bound to catch up with him. I notice he often uses a stick when walking now.’

‘One of his horses kicked him and he has a toe nail which has turned inwards and causes him pain now and then.’

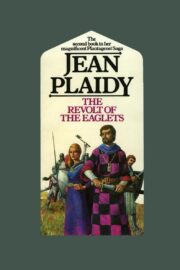

"The Revolt of the Eaglets" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Revolt of the Eaglets". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Revolt of the Eaglets" друзьям в соцсетях.