He wished that he could spend more time with Alice.

‘But now I am in England,’ he told her, ‘I shall see you more often. Will you always be so eager to see me?’

She assured him that she would.

He did not tell her that her betrothed Richard was asking that she go to him. He did not believe in spoiling such moments. Besides he had other matters with which to occupy him. He was particularly interested in his son Henry, whom he determined to keep beside him. This was not only because he did not trust him, he genuinely wanted to tutor him in the art of kingship. Young Henry had many good qualities. He was very good looking and quite charming. He had these assets which had never been his father’s. But he was frivolous and lacked his father’s dedication. He did not yet understand that to govern a kingdom – and particularly one which was so widespread – a ruler must never allow pleasure to stand in the way of his duty to his crown. He thought fleetingly of his Alice. Well, he compromised, hardly ever. And if the secret came out that he had taken Richard’s betrothed as his mistress, he would overcome that as he had other troubles. He would insist on a divorce. He would offer Louis marriage for his daughter … marriage to the King of England. And nothing would please him more.

Besides, when one had years of good rule behind one, one could take risks which an inexperienced man could not take.

So he would deal with this matter of his delightful Alice when the time came.

One of his first duties in England would be to visit the shrine of St Thomas, to pay homage to the saint who was now his good friend and working on his behalf in Heaven. There was now a new Archbishop, Richard, Prior of Dover, who had been unanimously elected and had held office for nearly a year. On the day he had been elected news had come from the Pope that Thomas à Becket’s name had been added to the list of saints.

Richard it seemed would not be a troublemaker, and for this the King was grateful. He could congratulate himself that everything had worked out very well.

As he travelled to Canterbury with young Henry beside him he received sad news from Count Humbert of Maurienne. His little daughter Alice who had been betrothed to Prince John had died suddenly. The King was momentarily dismayed and then it occurred to him that with John’s better prospects he might make a more advantageous match. It so often happened that these betrothals came to nothing. Children were affianced in their cradles and so it was small wonder that events occurred while they were growing up to prevent their marriages ever taking place.

John was now a free bargaining counter and his father would be alert for a more advantageous proposition.

And now to Canterbury.

The King watched his son as they rode. Too handsome, a little petulant still. And how insistent he had been that his homage should be accepted. Why was that? Had he really learned the folly of his ways?

He was surprised to find within himself a softness for his family. He would have liked a gentle wife – Alice of course – and a brood of sons and daughters who admired and loved him and thought only to serve him. Surely that was not asking too much? It was natural that fathers and sons should work together.

Something had gone wrong in the family. He had from necessity had to absent himself for long periods at a time, and Eleanor … It all came back to Eleanor. It was a great pity that he had ever married her. But was it? What of Aquitaine? She had been the richest heiress in Europe and he had been counted lucky to get her.

If he divorced her, he would lose Aquitaine. A sobering thought.

But this was not the time to think of that matter.

They were approaching Canterbury.

‘See my son there before us, the tower and spires of the Cathedral. I can never see it without emotion.’

‘That is not to be wondered at, Father,’ replied young Henry, ‘considering what happened there.’

‘It pleases me that I have made my peace with Thomas à Becket. We are now friends as we were in the beginning of our relationship. You and I are friends too, my son. Our strength is in our unity. Always remember that. I want you to know it and all England to know it. That is why I am going to make it known that you and I have sworn the oath of allegiance to each other. Who would dare come against us when we stand together?’

‘All know that we are friends, Father.’

‘Those close to us, yes … but I want all to know, so I am going to make a public declaration, that none may be in any doubt.’

‘What do you mean by this, Father?’

‘Never fear, my son, you shall see.’

Henry did see.

The King spent some time with his new Archbishop and declared himself pleased with him.

He told the Archbishop that he wished him to summon all the bishops of Westminster and he himself should accompany them. He would command all knights and barons to be present for he had something of importance to impart to them.

‘What is this conference, Father?’ asked young Henry.

‘You will see in good time,’ he was told.

There in the hall of the palace the King and his son were seated side by side on the dais and the elder Henry addressed the company.

He had summoned them for an express purpose.

‘You see me here with my son,’ he said, ‘and that there is amity between us. You know full well that but a short time ago the situation was very different. But I have excellent news for you. My son, King Henry, came to me at Bures and with tears and much emotion he humbly begged for mercy. He asked me to forgive him for what he did to me before, during and after the war. In all humility he begged that I, his father, would accept his homage and all allegiance declaring that he could not believe I had forgiven him if I did not. I was touched by this. My pity was great for I saw how remorseful he was to so humble himself before me. I put aside my grievances against him and I allowed him to pay homage to me. On holy relics he swore that he would bear me faith against all men and abide by my counsel and that he would order his household and all his state by my advice and henceforth in all things.’

The young King felt a violent resentment rising in him. It was true that he had promised this but that his father should have arranged this public declaration was humiliating in the extreme.

He had brought him here that the leading men of the nation should know that although he bore the title of King there was only one King of England and every man among them – including his son – was his subject.

His resentment flared up. He wanted to stand up and cry out that he had begged his father to accept his homage not because he had wished to serve him, but because he feared what might happen to him if he did not make such a declaration.

He would not endure such treatment. He had sworn his oath but he would await his opportunity.

The King felt it was good to be in England. He would always be King of England before anything else and this land was more important to him than any other, born and bred in Anjou though he had been. To lose England would be the greatest disaster which could befall a descendant of the Conqueror. There would be no danger of this if it were not for the fact that he must guard his lands so far away.

He kept young Henry with him, trying to win his affection. He was sorry for the young man and, though he was suspicious of him, wanted to be a father to him. He was learning that even a king could not command affection. He had tried to explain why he had made that public declaration of Henry’s homage to him. It was not to humiliate him. It was to show the people that they had sworn to be friends.

‘Was it not enough,’ asked young Henry, ‘that I had given you my oath?’

‘It was better that all should know you had given me your oath.’

‘I felt humiliated.’

‘Never be humiliated because you do your duty to your father. Be proud that you had the courage to confess your fault and glad that your father had the magnanimity to forgive you and take you back into his heart.’

He would have his son sit beside him at table and ride beside him in battle. He would have had the young man sleep in his room if it were not for the fact that Henry was a husband and he himself often preferred another bedfellow.

Alice, dear sweet Alice! She was changing; her body filling out as she was growing out of childhood into womanhood.

One day when he visited her she had disturbing news.

‘My lord,’ she said, ‘I believe I am pregnant with your child.’

He felt a mingling of horror and pleasure. Something would have to be done now. What? How could he write to the King of France and tell him that he had got his daughter with child? How could he tell Richard that his affianced bride was about to be a mother?

He looked at her and drew her to him holding her fast so that she might not see the expression in his face.

He had known that there was this possibility and had refused to look it straight in the face. He knew that when it happened there would be some change in his way of life, for Alice could not stay at the palace and bear a child which would be known to be his. And even if it were not – what a scandal there would be if the affianced bride of his son Richard should be in such a condition, when she had not been married and nowhere near her affianced husband for years.

How much was whispered already? His visits to this palace would have been noted. There must be many who were aware of his relationship with Alice. It was true that none would dare expose the secret for fear of his anger, but they would whisper of it.

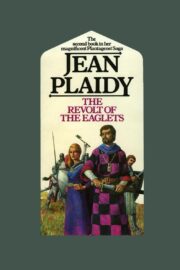

"The Revolt of the Eaglets" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Revolt of the Eaglets". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Revolt of the Eaglets" друзьям в соцсетях.