Young Henry was at his Court and with him was Philip of Flanders. A clever young man, this Count – energetic and eager to vanquish old Henry. And he was right when he said that the objective should be Normandy.

‘There should be no delay,’ said Flanders to Louis. ‘For depend upon it if we are to strike we must do so quickly. When the old warrior has settled his English affairs he will cross on the first favourable wind.’

Louis agreed that the objective should be Rouen, the first city of Normandy, for if Rouen fell it would have such an effect on the rest of Normandy that conquest would be made easy.

They would surprise the city and lay siege to it. This they did with great effect and the people of Rouen waited in their town for the coming of Henry, who, they were sure, could not delay long when he knew what was happening to their city.

Throughout his life Louis had been plagued by his religious training which had more than once intruded on his military designs. The siege was progressing favourably but it seemed likely that the coming of Henry to the rescue would not be long delayed. Louis then remembered that the Feast of St Lawrence was at hand and he did not see how he could do battle on such a day, so he declared a truce. There should be no fighting for a whole day and night. Rouen might consider itself released from siege for a day.

When this news reached the city the people went wild with excitement. It was an example, they said, of Louis’s ineffectual generalship. The King of England must be on his way to save them and every hour was important to them. The folly of the King of France must surely have saved them.

So delighted were they that there was singing and dancing in the streets. They believed that the siege of Rouen was all but over. They threw open the gates of the city and some of the knights staged a tournament in the fields outside the city walls.

The French soldiers watched the proceedings with dismay, but none was more put out than Philip of Flanders.

So incensed was he that he forgot his reverence for the crown of France and stormed into the King’s tent. Louis looked pained, but he was well known for his mildness and he bade the Count of Flanders have his say.

‘My lord King,’ cried Philip, ‘the King of England is on his way. He cannot be long delayed. You may depend upon it news has reached him of the state of siege which exists in Rouen. In permitting this truce you give him an opportunity to come in time to save the city.’

‘If he comes we will face him.’

‘We shall lose Rouen.’

‘St Lawrence in whose honour we have called this truce will aid us.’

‘And what of St Thomas à Becket whom he will summon to his aid?’

‘St Thomas would never aid him.’

‘But he has done penance at his shrine. He has allowed himself to be whipped.’

‘He is his murderer.’

‘It was not his hand that struck the blow and see what success he has had in England since his penance.’

Louis was a little shaken. He had great faith in St Thomas à Becket. But it was he, Louis, who had given the Archbishop sanctuary in France and it had never been necessary for him to do penance at his shrine.

‘My lord King,’ implored Philip of Flanders, ‘if this truce goes on through the day and night we shall lose Rouen.’

‘I have given my word and said my prayers to St Lawrence.’

‘St Lawrence can do nothing against the King of England,’ said Philip almost impatiently, and he added: ‘My lord, might it not be that this opportunity comes through St Lawrence? The city gates are wide open; the knights are sporting in their tournament. Could this not be the time to go into the attack?’

Louis was horrified. ‘I have given my word.’

Philip of Flanders tried to hide his scorn. All his life the King of France had lost opportunities on the battlefield. Was he now doing the same?

Philip wrung his hands. He went away and left the King of France saying his prayers to St Lawrence. Shortly after, Philip returned to the King’s camp and with him came young Henry. The young King threw himself on his knees before the King of France.

‘My lord, hear me,’ he cried. ‘My kingdom is at stake. We can take Rouen now if we surprise the city. Soon my father will be here with his troops. We must take the city before he comes.’

‘I have declared a truce,’ persisted Louis.

The two young men joined in their entreaties. They pointed out to him what victory would mean. Was he going to throw it away because of a promise? It might be that if he did not give way many French soldiers would lose their lives.

‘Then,’ he said, ‘let us exploit the situation. Let us make ready to take the city while the gates are open to us.’

Before he could change his mind Philip and Henry hurried away to give orders that immediate preparations should be made for capturing the city.

Rouen might have been taken with the utmost ease but for the fact that a group of young men had dared two of their number to climb the church tower. This they did and as they were poised there, they could see beyond the city to those fields where the French army was encamped and it was obvious to them that preparations were in progress for an immediate attack.

Coming down they told what they had seen and within a few minutes the church bells were ringing out a warning. This was the sound for alarm. The knights at their tournament heard it; they hurried into the city; the gates were closed; boiling pitch was prepared and carried to the battlements. Everyone was ready for action and determined to hold Rouen with an even greater determination because of the perfidy of the French in violating a truce which they had proclaimed.

Thus when Philip of Flanders and young Henry led the attack they were repulsed. The surprise was lacking; the citizens were ready for them and their little strategy might never have been.

All through the night the battle raged and the next day the watchers from the city’s walls gave a great shout of joy for the King of England’s army was seen approaching. The siege would soon be over.

In a short time the English were within sight of the French and the battle was about to begin. Louis, who was not averse to besieging a town, disliked the thought of hand-to-hand battle. He had never lost his revulsion to bloodshed and he now heartily wished that he had never embarked on the campaign to take Rouen. When he heard that the English had already attacked his rear-guard and inflicted severe casualties, he was so sure he could not win in a hand-to-hand fight that he sent messengers to Henry to ask for a truce and request that he might retire with his troops some miles from the town where he and the King could parley.

Not realising at this stage that the French had perfidiously broken the truce they had made with the citizens of Rouen and secretly not wishing to do battle with an army in which his son was fighting against him, Henry agreed to allow the French to withdraw.

He was not surprised nor was he displeased when news was brought to him that during the night they had fled and had not stopped riding until they crossed the borders of France.

Henry laughed aloud. It was always good to force a retreat without the loss of blood. That was an easy victory. He only had to appear, to strike terror into his opponents. This would teach young Henry a lesson. He would see that it was not easy to oppose his father.

What rejoicing there was when he entered his city of Rouen! He praised those valiant men and women who had withstood the siege. He sent for the young men who had climbed the tower and when he heard their story he embraced them.

‘You did well,’ he said. ‘It shall not be forgotten.’

Whether it would or not remained to be seen, for Henry was one who often forgot his promises; but he could always make people happy because they had won his approval to such an extent that he made the promise.

He went into the church and gave thanks to God and St Thomas à Becket, for he was certain that it was the Archbishop who had sent those men up to the tower and had saved his city of Rouen.

Richard, the King’s second son, was not yet eighteen. More warlike than his brothers, he exulted in the necessity to take up arms. He was determined to excel on the battlefield and to hold Aquitaine against his father. He hated his father. It was true that his brothers were impatient with the old King, that they believed, he had cheated them of their inheritance, that they had taken up arms against him, but none of them hated him as Richard did.

All his life he had seen his father as the devil – the evil genius of their life. His mother had believed this and she was wise and clever and he loved her even as he hated his father.

He longed to be with her, but she was her husband’s captive. When Richard thought of that he was so filled with fury that he longed to kill his father. And he would, he promised himself. How gleefully he would cut off his head and send it to his mother. She would appreciate that. Together they would make a ballad of it; they would sing it in harmony.

He had a double mission now – it was not only to defeat his father and become true ruler of Aquitaine but to set his mother free. He wished that he were older. He was a born fighter but no one took so young a man seriously, and his father had created an aura about himself; he was becoming known as the invincible lion. Yet he was ageing, and it would not always be so. The King of France was against him; so were his other sons, Henry and Geoffrey. Surely he could not stand out for ever against such opposition? And when the Archbishop had been murdered it seemed as though the whole world was against him. Could people have admired him for performing that humiliating penance? Richard could not believe this could be so. Surely he had demeaned himself, and yet since he had done it, he had had great success in England. Attempts to take it from him had failed. But it would be different in Normandy and Aquitaine. He was not going to win there.

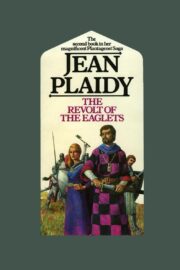

"The Revolt of the Eaglets" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Revolt of the Eaglets". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Revolt of the Eaglets" друзьям в соцсетях.