This was a ruler’s nightmare, when his dominions were so scattered and trouble arose in several places at once.

One of his men came in to tell him that a knight was without who wished to have urgent speech with him.

He commanded that he should be brought to him. Fresh trouble? he wondered. Where would the next rebellion be?

But this man’s news was different.

‘My lord,’ he explained, ‘we were riding near to Chartres when we came upon a party of Poitevin knights. We were of the opinion that they were riding to join the enemy so we captured them.’

The King nodded. The right act but scarcely one to report to him.

‘There was one among them, my lord, who aroused our suspicions. We formed the opinion that she was a woman.’

A woman. The King grimaced, but the knight’s next words made him stare at him in amazement.

‘She proved to be the Queen, my lord.’

‘The Queen! My wife!’ cried Henry.

‘’Twas so, my lord. She admitted it and there was indeed no doubt.’

Henry started to laugh. He stopped abruptly. ‘Where is she?’

‘We have brought her to you, my lord, not knowing your wishes.’

Henry went to the knight and slapped him heartily on the back. ‘You did right,’ he said. ‘By God’s eyes, I promise you I’ll remember you for this deed. She is here then. Bring her to me. I would have speech with my captive.’

It was indeed Eleanor. She stood there before him, anger in her eyes, defiance, hatred, everything he remembered so well.

‘Leave us,’ he commanded. Then he stared at her and gave vent to loud laughter.

‘So you have joined the army, eh?’

‘It behoves all men and women to fight against tyranny.’

‘Brave words from a prisoner. Captured, eh? Where were you going?’

‘To join my sons.’

‘And you were going into battle with them against their father?’

‘Nothing would please me more.’

‘You are a little old for such activities. These are not the days when you rode out to the Holy Land and had great sport on the way with your uncle and the infidels. You see what happens? You are captured before you reach your objective. I’ll wager you were on your way to the Court of France. Did you hope that now that you are old your first husband might be more to your taste than he was in your lustier days?’

‘It surprises me not that Henry the Lecher’s thoughts run always in one direction. My project was to gain for my sons that which is their right.’

‘You talk nonsense. I am the King. What I hold I hold by right and conquest. You are a foolish woman and you shall learn this for you are my prisoner and I swear that you shall never again be free while I live to make discord between me and my sons.’

‘What do you mean? You will throw me into a dungeon?’

‘What I intend to do you will know ere long.’

‘Do you think your sons will allow you to insult their mother?’

‘My sons will learn, as their mother will, who is the King and ruler of them all.’

She came towards him, her arm uplifted. He caught her in his strong grip and she cried out in pain. Their faces were close, hers distorted by hatred, his triumphant. He thought: My luck has changed. This is the greatest good fortune. She can make no more trouble for me. And when the world knows that she is my prisoner they will realise that Henry Plantagenet is still the man he was and even the wrath of Heaven does not dismay him.

He shouted to the guards at his door.

‘Take this woman,’ he said. ‘Keep her in close confinement. Guard her. It will go ill with any if she escapes.’

Eleanor looked over her shoulder at him as she was dragged away, but the venom in her expression only made him laugh.

Those were uneasy months which followed. Richard de Luci with Humphrey de Bohun, now Constable of England, had held back the Scottish invasion and had been able to establish a truce with William of Scotland. Henry had held at bay the rebellions which had sprung up over Normandy and Anjou with alarming frequency.

He was constantly afraid that Eleanor would get away. He was determined to take her to England and see that she was incarcerated in a prison there from which she could not escape.

He could not help feeling that some power was against him and it occurred to him that until he confessed his guilt in Thomas’s murder and asked forgiveness for this ill luck would be his.

There was a glimmer of brightness when the Earl of Leicester who had landed in England was completely routed by Henry’s supporters. The King was exultant. This would show young Henry that he could not defeat his father as easily as he believed. And what were his sons thinking now that he held their mother captive?

While he was congratulating himself that he was going to suppress all those who rose against him, urgent messengers arrived from England.

At first the King listened to their warnings but decided that his presence was needed in Normandy, but as they became more insistent he realised that it would be folly for him to stay in Normandy to protect his possessions there while he lost England.

He made up his mind that he would cross to England without delay taking with him his captive Queen for he imagined what havoc she could cause if left behind. She might prevail on someone to release her and if she were free he could expect trouble from her direction. The safest place for Eleanor was in the stronghold of some castle and her guardian should be someone whom he could trust.

He would also take with him Marguerite, young Henry’s wife, who by good fortune was in his custody, for her very relationship with his son would make her his enemy.

He had another matter very firmly in his mind. He must stop this chain of disaster. He would no longer pretend he was guiltless of Becket’s murder, for it seemed very likely that the events of the last year were due to what had happened in Canterbury Cathedral. It seemed to him that not until he obtained absolution could he hope for better fortune.

His kingdom, as well as his soul, was in peril.

He must save them both.

He was thoughtful as he rode to the coast. He fancied that what he was about to do would be smiled on by Heaven and once it was done – distasteful as it was – he would cease to be plagued by ill luck.

A gale was blowing and he could see the fear in his companions’ faces but he was determined to delay no longer. He was going to do what should have been done a year ago and only when it was completed would he be safe from his enemies.

‘My lord,’ said his advisers, ‘we cannot sail in this wind.’

‘We are putting to sea without delay,’ he told them.

They were dismayed but they dared not disobey and when they were ready to sail it seemed that the wind changed. It was behind them and blew them across the Channel. The King was pleased.

‘You see,’ he declared, ‘you may always trust my judgement.’

Exultantly he went to see the Queen.

‘So here you are!’ he said. ‘Far from your troubadours! You will not find your jailers so ready to sing to you.’

‘Think not,’ she answered, ‘that my sons will allow me to remain your prisoner.’

‘They must take care that they may not soon be in like case. By God’s eyes, I will teach all what it means to rebel against me.’

‘Take care that they do not teach you what happens to tyrants.’

‘You are too bold, Madam, for a woman who is in the hands of her enemy.’

‘Not for long.’

‘For as long as I shall live, my lady.’

‘It was an ill day for me when I first set eyes on you.’

‘Take pleasure, Madam, in knowing that that day is even more regretted by me.’

How strong he is, she thought, with grudging admiration. Every inch a king. And her mind went back to the days when she had determined to marry him and how she had longed for the time when they could be together.

‘I can assure you that your regret could not be greater than mine,’ she told him. ‘But you are a deceitful man for you led me to believe that once I was important to you.’

‘It was before I learned to know you.’

‘Aye, and I also had bitter lessons to learn. If you had not been such a lecher we might have worked together.’

‘You, Madam, are scarce in a position to criticise others for that fault. Before our marriage you took strange bedfellows.’

‘Never such a tyrant as my second husband.’

‘We waste time, and I have none to spare. I sent for you to tell you that you are to be taken to Salisbury Castle and there you will remain until it pleases me to change your residence. But think not that you will go free. You have offended me too much. You have proved yourself to be a traitor, and though you are my wife shall be treated as such.’

It occurred to him that he might bargain with her for a divorce. Would that be wise? To have her free to communicate with his sons? No. This was not the time to speak of divorce when he was currying favour with Heaven by doing penance for his part in Becket’s murder.

He must be quiet about that matter for a while. Moreover what if he procured a divorce? Could he marry Alice? And what of Rosamund? Clearly it was better at this time to say nothing of divorce – not to think of divorce. His mind must be free to consider Becket’s murder and the fact that he deplored it and repented for any part he might have had in bringing it about.

He watched his wife through narrowed eyes. Traitor! Any king was justified in imprisoning a traitor who threatened his realm … even though that traitor should prove to be his own wife.

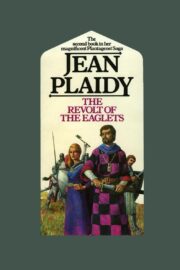

"The Revolt of the Eaglets" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Revolt of the Eaglets". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Revolt of the Eaglets" друзьям в соцсетях.