Chapter III

THE KING AND QUEEN

The King set out for Normandy accompanied by his son who made little effort to disguise his displeasure. The boy was distinctly sullen, but his father’s thoughts were occupied with too many other matters to concern himself greatly with young Henry.

He could not stop thinking of the adorable Alice and what a pleasure it would be to get back to her. He would take her from the nursery and install her in the palace. There would have to be some secrecy of course. He had to think of Rosamund to whom he was still devoted; but Rosamund must know that he could not have married her even if he divorced Eleanor, although he had once contemplated this and mentioned it to her. Perhaps he had been wrong in that and it was due to this that she had become obsessed by the idea that she was living in sin. He remembered tenderly so many aspects of their relationship. He still needed Rosamund but he wanted Alice with an intense desire which could not be held in check. Alice, daughter of old Louis, King of France! That old monk! It amused him really. Alice – conceived not in passion but because of the duty to France to get a child. And this perfect creature had been produced for his pleasure. If I made her Queen of England Louis would not object. Only Eleanor stood in his way. It might well be that Eleanor would like to marry again. She had always been a very energetic woman. What was she doing in Aquitaine surrounded by her troubadours? How many of them did she take to her bed? Women like Eleanor were never too old.

There were other less pleasant matters to take his mind off a future shared with an eager-to-please Alice minus sour Eleanor and a docile understanding Rosamund in the background of his life.

No sooner had he landed in Normandy than messages arrived from those Cardinals Theodwine and Albert to the effect that they were waiting for him at the Monastery of Savigny.

In ill humour so that all men feared to approach him lest he fly into a temper over the slightest fault, the King rode to the monastery. That he, the King of England, should be so summoned was inconceivable. And yet not so. He had to face the fact that the Pope was more powerful in Christendom than the King of England. Was that not what the quarrel between himself and Thomas à Becket had been about?

Inwardly he cursed the Pope, as coldly he greeted the Cardinals. He had come far, he told them irritably, and at great inconvenience, to see them. He had been engaged on an important campaign in Ireland. Out of respect for and honour to His Holiness he had come, but he would like them to state what it was the Pope wished of him without delay for matters of importance demanded his attention.

‘This,’ Cardinal Theodwine told him, ‘is of the utmost importance, my lord King. It concerns not your temporal power but the very existence of your soul.’

Henry was a little shaken. He never doubted for a moment that he could outride any earthly storm, but the thought of the unknown could rouse fear in most men; and living the life he did how could he be sure that he might not any day come face to face with death? It was never far from the battlefield and a King might become a victim of the assassin’s lance or arrow at a moment’s notice. Every night retiring to his bed, he would be justified in fearing that he might never see the light of day.

Thomas had been cut down in the full flush of spiritual glory. A curse on Thomas! There was no escape from him.

‘What will be required of me?’ he growled.

‘It would be necessary to perform some penance.’

‘Penance! I! For what reason? Do you hold me guilty of this murder?’

‘Those who did the deed were your men. They acted on your orders.’

‘I gave no such orders, nor shall I permit it to be said that I did.’

‘My lord, it will be necessary for you to swear to that.’

‘Necessary! Who makes such rules? You forget, sir, that you speak to the King of England.’

‘We act on the instructions of His Holiness the Pope.’

‘I tell you I am master here.’

‘We come from the spiritual master of us all,’ answered the Cardinals.

‘I would remind you that these are my lands and you would be well advised to remember it.’

He was fighting to control his temper. He could feel the blood rushing to his head.

Cardinal Albert said: ‘We will leave you, my lord, to consider what must be done. We will confer again tomorrow.’

In the chamber they had set aside for him he clenched his fists and bit them until they were red and blue with his teeth marks.

‘By God’s arms, eyes and teeth!’ he cried. ‘Thomas, you will not let me rest. I would to God I had never seen you. Why could you not have died in your bed?’

He was too wise and shrewd to believe he could defy the Pope. If he did, as soon as he left Normandy the rebellions would start. He would have to stay here to hold them in check. And what would be happening in England while he did that? He had his enemies there. Excommunication, a loss of his lands. No, he must be wise. There was nothing for it. He must give way.

It was in a chastened mood that he met the Cardinals on the next day.

‘Well,’ he cried, ‘what is it you desire of me?’

‘We desire this, my lord. You must hold the Holy Gospels in your hand while you swear that you did not order nor wish the death of Thomas à Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury.’

Henry was thoughtful. Of course he had wished it. Who would not have wished the death of a man who caused so much trouble? He had demanded of his knights why they did not rid him of the tiresome cleric. But, he assured himself, I did not wish the murder of Thomas. He was my dear friend, and I would to God he had not been so brutally killed in the Cathedral.

He took the gospels in his hands. It’s true, Thomas, he thought. I would we were together again as we used to be when we roamed the countryside together. I always wanted that. It was only when you became my Archbishop that there was this trouble between us.

They were demanding of him some sort of penance. Why, if he had had no part in the murder? It was easier to grant what they asked than to swear on the holy book.

‘My lord, the Pope asks that you support two hundred knights for the defence of Jerusalem for a year.’

‘I will do this,’ said Henry. It was always simple to promise money for there were invariably so many reasons why such promises could not be kept.

‘You will allow appeals to be made freely to the Pope.’

Now they were tampering with the Constitutions of Clarendon over which he and Thomas had quarrelled. Well, if it must be, it must. He would have to extricate himself from this unpleasant affair as quickly as possible and get on with the important business of safeguarding his realm.

‘You must restore the possessions of the See of Canterbury so that they are as they were before the Archbishop left England.’

‘Yes,’ he agreed.

Finally, English Bishops must not be asked to take the Oath he had demanded of them at Clarendon; and those who had taken it must be freed from any obligation to keep it.

He must put an end to this humiliating situation. He must make his peace with the Pope.

He could have murdered those Cardinals. He could have gone into battle against the Pope. But he was not called the most shrewd king in Europe for nothing. He knew when concessions had to be made and this was one of those occasions.

He had settled the matter, he believed, once and for all.

And Thomas, my beloved friend and hated enemy, you in your shrine at Canterbury have defeated the King of England on his throne. The battle is over, Thomas, and I can say with truth that I wish with all my heart that it had never been necessary to indulge in it.

He left Savigny with rising spirits. He was free of Thomas.

There was news from Eleanor. Richard was now of an age to be officially declared Duke of Aquitaine, and she believed that the ceremony of establishing him as such should no longer be delayed.

He agreed with her. Let Richard be the acknowledged Duke of Aquitaine. When he considered what he had done to Richard’s betrothed it soothed his conscience a little to agree readily to his acquisition of Aquitaine. Eleanor was for once pleased with him, and when they met at Poitiers she was quite gracious to him.

Richard viewed him with suspicion. It was almost as though he knew how his father had betrayed him with Alice. But no, Richard had always disliked him and he had always disliked Richard. It seemed strange that a man could feel so about such a good-looking son of such promise, for Richard excelled in horsemanship, swordsmanship and chivalry far more than any of his brothers. He was a poet too, so perhaps it was because he was very much his mother’s son that his father could not like him.

With the thought of Alice always in his mind now he liked him even less as he must one whom he had wronged so deeply, for if he were completely honest he could not rid himself of the thought that it might be necessary for Alice to be Richard’s bride after all. He would delay it as long as possible. In any case it was a matter about which he did not wish to think.

It was a grand ceremony at Poitiers where this fifteen-year-old golden boy took the abbot’s seat in the Abbey of Saint-Hilaire where he accepted the lance and banner of the Dukes of Aquitaine, the insignia of his new office.

How the people cheered! And Eleanor looked on, softened for once by her affection and pride in this favourite of all her sons.

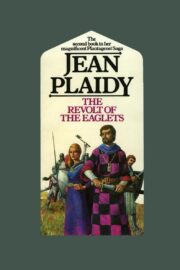

"The Revolt of the Eaglets" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Revolt of the Eaglets". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Revolt of the Eaglets" друзьям в соцсетях.