She agreed to it, but added after a moment’s reflection, “And yet if he does so, who can tell what horrors may next be in store for me?”

“None, upon my honor.”

“Very pretty, my lord, but I have frequently been forced to observe the remarkable disparity that exists between my notions of what is horrid, and yours. Are you ever put out of countenance?”

“Very often.”

She smiled a little archly. “Will you think me very saucy, my lord, if I say that that confession gives me an excessively odd idea of the life you must lead at the Hall? For you have treated as the merest commonplaces every shocking event that has occurred in the last week, from your cousin’s death at Nicky’s hands, to the discovery that you have stumbled upon a dangerous treason. These things appear not to have the power to disturb the tone of your mind! I envy you!”

“Well,” he said reflectively, “two of my sisters and my brother Harry were forever doing such outrageous things that I think I must have grown out of the way of being very much surprised at anything.”

She laughed and rose rather shakily to her feet. He put his hand under her elbow to assist her, and escorted her to the door. She parted from him in the hall, declining his offer to take her upstairs. “Indeed, I am quite well now! You do not mean to go to London again, I hope?”

“No, I am fixed in Sussex for some time, I believe. You have only to send a message over to the Hall if you should wish to speak with me. May I again impress upon you that you have no need to feel any further alarm?”

She looked quizzical, but as the doctor just then appeared at the head of the stairs, returned no answer but went up, leaning on the banister rail and saying,

“You mean to scold me, Dr. Greenlaw, but indeed I am going to my room, and I have drunk all that horrid mixture!”

“I am glad of it, ma’am. I can assure you you will be the better for it. I shall call tomorrow to see how you are going on, if you please.”

She thanked trim. He waited for her to pass him and then went on down the stairs to where Carlyon stood in the hall. “If you will pardon an old man who has known you from your cradle, my lord,” he said bluntly, “I do not understand how that lady came by that bruise on her head, but I will go bail there is some devilment afoot here!”

“I will readily pardon you, but if this is intended as a reproach to me it falls wide of the mark. I assure you I did not give Mrs. Cheviot her bruise.”

The doctor smiled grimly. “Very well, my lord, I know how to hold my tongue, I hope.”

“How do you find Mrs. Cheviot?”

“Oh, she will do well enough! Someone struck her a stunning blow, however—for all you may say she fell and so hit her head, my lord.”

“And your other patient?”

The doctor grunted. “I can find nothing amiss with him beyond a pronounced irritation of the nerves. I have prescribed a few drops of laudanum, but as for sore throats, I see no sign of such a thing!” He looked up under his brows and added, “Master Nick would have me scare him away with a tale of smallpox in the village, but you may tell him, my lord, that whatever it may be that has occurred at Highnoons, it has given him a pronounced dislike of the place, so that I fancy he will not be plaguing Mrs. Cheviot for much longer. As for Master Nick himself, your lordship will like to know that I constrained him to let me take a look at his shoulder when he caught up with me today, and I find it healing just as it should.”

“Why, thank you! He was always one to mend quickly.”

“Fortunately for himself!” Greenlaw said, in his sardonic way. “He tells me you had my Lord and Lady Flint with you for a night. I trust her ladyship enjoys her customary health?”

He lingered for a few minutes inquiring after the various members of Carlyon’s family, and then put on his coat and departed. Carlyon went back into the bookroom.

Here Nicky found him some fifteen minutes later. Nicky came in with a worried frown on his face, saying that he had been whistling and calling to Bouncer all through the home wood and feared he must have strayed on to Sir Matthew’s land.

“Then you had best recover him without any loss of time,” Carlyon said.

“Yes, I know I had, and I have the greatest dread that he may be caught in a trap, or perhaps shot by one of those brutes of keepers. For Sir Matthew swore he would tell them to shoot him if he disturbed his birds, and—”

“Well, I fancy Sir Matthew will not proceed to those lengths, but you should certainly go to look for him or you will find yourself quite in Sir Matthew’s ill graces.”

“I don’t care for that if only poor old Bouncer is not in trouble. You know, he did once get stuck in a fox’s earth, Ned, and had to be dug out. I own, I would wish to set out to search for him at once, only do you ought?”

“Most decidedly I do.”

“Yes, but there is Francis Cheviot to be thought of, after all!” Nicky reminded him.

“I am sure Bouncer is more important than Francis Cheviot.”

“I should just think he was! Why, he is worth a dozen of him! Only fancy, Ned, he barks at Francis whenever he sees him! And I did not teach him to do so! He is most intelligent! I have not let him bite Francis though, because with such a mean fellow there’s no saying what might come of it. I do wish he would come in!”

“From my knowledge of him, he is not at all likely to do so before nightfall.”

“Ned, I cannot be dawdling here when he may be caught in some trap!”

“My dear boy, there is no reason why you should.”

“Very well then, I shall go out after him. But I warn you, Ned, it may be hours before I find the old fellow, and while I am gone Francis may be up to some more of his tricks!”

“Unlikely, I think.”

“Of course,” said Nicky huffily, “if you do not choose to tell me what you have in your head you need not, but I think it pretty shabby of you!”

Not receiving any other answer to this than an amused look, he left the room with a dignified gait and was soon striding off in the direction of Sir Matthew Kendal’s lands. Carlyon left the bookroom and desired Barrow to send for his chaise from the stables. Miss Beccles found him drawing on his gloves in the hall, and said diffidently and a little anxiously, “You are leaving us, my lord?”

He smiled and nodded.

“I dare say there is no need for you to remain, sir?” she ventured.

“None, I believe. I have already begged Mrs. Cheviot to think no more of what has happened here today.”

“I am sure if you feel it to be safe for her to remain here, my lord, it must be so indeed,” she said simply.

His eyes lit with amusement but he let it pass, merely bowing and saying in a perfectly grave tone, “You are very good, Miss Beccles.”

“Oh, no! When it is you, my lord, who—Indeed, I am all obligation! Such distinguishing observance! Never backward in the least attention! I am sure we may place every dependence upon your lordship’s judgment. And as for—Well, I am sure when dear Mrs. Cheviot has been in a pucker, I have said to her a dozen times: “Depend upon it, my love, when his lordship comes, everything will be in a way to be settled!’”

He looked a trifle rueful. “And what does Mrs. Cheviot commonly reply, ma’am?”

The poor lady colored up and became entangled in a riot of half sentences from which it emerged that although dear Mrs. Cheviot had a mind capable of every exertion, indeed something more of quickness than most females, the awkwardness of her situation had inclined her to indulge lately in odd humors.

“I fear Mrs. Cheviot has no very high idea of my management,” he remarked.

“Oh, my lord, I am sure—I She has a kind of sportive playfulness which—But your lordship has such a superior understanding! I need not make the least excuse for the occasional liveliness of Mrs. Cheviot’s manners!”

“Not the least,” he agreed. “Does she abuse me soundly?”

“You know it is her way to indulge in a good deal of raillery, my lord!” Miss Beccles explained earnestly. “Then she has been so much on the fidgets, you know! I am sure it is no wonder! But with every disposition in the world to fancy herself able to contrive all without assistance, and perhaps with a little distaste of submitting to authority, it cannot be called in question that she can only be comfortable when your lordship is so obliging as to advise her how she should go on.”

He held out his hand. “Thank you. I depend upon your good offices, Miss Beccles. Good-by! I shall be at Highnoons again tomorrow.”

He was gone, leaving her to blink after him in bewilderment.

Less than an hour later, having assured herself that Elinor lay deeply and peacefully asleep, Miss Beccles, herself conscious of being very much exhausted by the events of the morning, went downstairs with the intention of desiring Mrs. Barrow to send some tea and bread and butter to the parlor on a tray. She was brought up short by the sight of Francis Cheviot standing in the hall enveloped in his fur-lined cloak, a muffler swathed about his throat, and his hat already in his hand. He was giving Barrow some languid directions, but he turned when he heard the governess’s footsteps on the stairs and said, “Ah, I am happy to have this opportunity of addressing you, ma’am! I would not have you sent for, in case you should be ministering to poor dear Mrs. Cheviot, but I am glad you are come—very glad! And how does the sufferer find herself?”

“Mrs. Cheviot is asleep, sir, I thank you,” she replied, dropping him a prim little curtsy.

“One hoped she might be. ‘Great nature’s second course,’ you know. Upon no account in the world will I have her disturbed!”

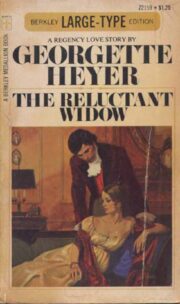

"The Reluctant Widow" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Reluctant Widow". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Reluctant Widow" друзьям в соцсетях.