“I’m in the hall,” his voice answered her, a trifle faintly but reassuringly cheerful. “The devil’s in it that I missed the fellow!”

She hurried down the stairs, holding the lamp up, and saw him rather unsteadily picking himself up. “Nicky! Good God, do not tell me he did indeed come back?”

“Come back? Of course he did!” Nicky said, cautiously feeling his shoulder. “What’s more, I should have had him if you would not keep a damned suit of armor in the stupidest place anyone ever thought of!

Oh, I beg pardon! But indeed it is enough to try the patience of a saint!”

“Nicky, you are hurt!” she cried, quite horrified. “Oh, if I had dreamed that anything was likely to happen I would never—My poor boy, lean on me! Did he fire at you? I heard two shots and I was never more shocked in my life! Good God, you are bleeding! Let me help you into a chair this instant!”

“I think he winged me,” said Nicky, allowing himself to be assisted to a tattered leather chair and sinking down into it. “I never touched him, but I did shatter his lantern, and that would have been pretty fair shooting, I can tell you, if I had been aiming at it. But it is the most cursed mischance, Cousin! I have no notion who he was or what he wanted, except that he was making for the bookroom, which I guessed he would be in any event.”

“Oh, never mind that!” she said, setting the lamp down on the table and running to shut the front door.

“As long as you are not badly wounded! Oh, what in the world will Lord Carlyon say to this? I am culpably to blame!”

Nicky grinned feebly. “Hell say it was just like me to make such a botch of it. Don’t be in a taking! It’s only a scratch!”

By this time Barrow had appeared on the scene, a tallow candle held waveringly in one hand and on his face an expression compound of amazement and consternation. He was sketchily attired in breeches and his nightshirt, but he forgot this unconventional raiment when he saw Nicky clutching one hand to his left shoulder and came hurrying down the stairs, clucking with dismay. He was almost immediately followed by his spouse, scolding and exclaiming at once. Between them, she and Elinor eased the coat from Nicky’s shoulders and laid bare a wound which, though it bled nastily, Mrs. Barrow announced to be not by any means desperate.

“I believe you are right!” Elinor said, with a sigh of relief. “It is too high to have touched any fatal spot! But a doctor must be fetched instantly!”

“Oh, fudge! It’s nothing!” Nicky said, trying to shake them off.

“Be still, Master Nicky, will you?” said Mrs. Barrow. “Likely you have the ball lodged in you! But who fired at you? Sakes alive, what is the world acoming to? Barrow, don’t stand there gawping! Fetch some of Mr. Eustace’s brandy to me straight, man! Oh, dear, what a hem setout this is, to be sure!”

Elinor, meanwhile, had snatched Barrow’s candle from him and had hurried into the bookroom. She came back with one of the tablecloths she had been mending in her hand, and began to tear it into serviceable strips. Nicky was looking very faint and had his eyes closed, but he revived when Barrow forced some brandy down his throat, choked, coughed, and again said that it was only a scratch. Elinor ordered Barrow to support him upstairs to the spare bedroom, and followed anxiously in their wake carrying the torn cloth and the brandy bottle. By the time Nicky had been laid upon the bed Mrs. Barrow had fetched a bowl of water and was ready to bathe his wound. She and Elinor stanched the bleeding and bound the shoulder as tightly as they could. The patient smiled sweetly up at them and murmured, “What a rout you do make! I shall be as right as a trivet by morning.”

“Great boast, small roast!” grunted Barrow, covering him with the quilt. “I’d best ride for the doctor, no question. But who shot you, Master Nicky? Don’t tell me that plaguey Frenchy was in the house again, because I double-bolted every door, and so I’ll swear to, sure as check!”

“I don’t know if it was he or another,” Nicky replied, shifting uneasily on his pillows. “I didn’t mean to tell you, but he came in by a secret stair that goes down the bakehouse chimney. I found it this morning.”

Mrs. Barrow gave a scream and dropped the strip of linen she was rolling into a bandage.

“Do-adone, Martha!” said Barrow, happy to be able to take a lofty tone with her. “Master Nicky’s gammoning you. That old stair’s been shut this many a year!”

“Well, it has not,” said Nicky, nettled to find that Barrow knew of his discovery. “And I’m not gammoning you! I was in that room where the entrance to it is and I saw this fellow come out of the cupboard.”

Mrs. Barrow sat down plump upon the nearest chair and expressed her conviction that she was unlikely ever to recover from the shock her nerves had sustained,

“You shouldn’t ought to have stayed there without me to see you didn’t come to no harm, Master Nick!” said Barrow. “The cat’s in the cream pot now, surely, for what his lordship will have to say about this night’s work I daren’t, for my ears, think on! If it ain’t like you, sir, to be flying at all game, and never no thought taken to what may come of it! Ah, well, I’ll saddle one of the horses and fetch Dr. Greenlaw to you straight!”

“But what in the name of heaven can anyone want in this house?” demanded Elinor.

“There’s no saying what any Frenchy may want,” said Barrow austerely, “but you can lay your life, ma’am, it ain’t anything good.”

Chapter IX

It was fully an hour later when the welcome sound of voices in the hall informed Elinor that the doctor had arrived at Highnoons. She had found time to dress herself. Mrs. Barrow had roused the obliging wench from the Hall and told her to make up the smoldering fire in the kitchen and to set water on it to boil, while she herself, taking a high tone with Nicky, bullied and coaxed him into permitting her to undress him and get him between sheets. He was so much discomfited by some of the more embarrassing reminiscences of his extreme youth which she saw fit to recall to his memory that his protests lacked conviction, and she had less trouble with him than might have been expected.

Dr. Greenlaw opened his eyes a little at sight of Elinor, but bowed to her very civilly before turning his attention to his patient.

Nicky smiled at him. “You are never done with us, Greenlaw!” he remarked.

“Very true, Mr. Nick, but I am sorry to find you in this case,” replied the doctor, beginning to unwind the bandages. “What scrape are you in now, pray?”

“The devil’s in it that I don’t precisely know,” Confessed Nicky. “But if only I had not missed the fellow I should not care!”

“Barrow has been babbling some nonsense about Frenchmen. Was it a housebreaker, sir?”

“Yes, of course,” Nicky said, with a warning glance cast in Elinor’s direction. “Well, what’s the damage? It’s only a scratch, isn’t it?”

“Ay, you were born under a lucky star, sir, as I have told you before,” said Greenlaw, opening a case of horrid-looking instruments.

“Yes, when I fell off the stable roof and broke my leg,” said Nicky, eying his preparations with some misgiving. “What are you meaning to do to me, you murderer?”

“I must extract the ball, Mr. Nicky, and I fear I shall hurt you a trifle. Some hot water, ma’am, if I might trouble you!”

“I have it here,” Elinor said, picking up the brass can from before the fire and hoping that she did not look as queasy as she was beginning to feel.

But she and Nicky alike underwent the ordeal with great fortitude, Elinor by dint of turning her eyes away from the doctor’s probing hands, and Nicky by gritting his teeth and bracing every muscle. The doctor encouraged them both with a gentle flow of irrelevant conversation to which neither attended. Elinor was glad to discover that he was deft and quick. The ball was not deeply lodged and was soon extracted, and the wound washed and dressed with basilicum powder. Greenlaw bound it up comfortably, measured out a cordial, and obliged Nicky to swallow it. “There, you will do very well, sir!” he said, drawing the bedclothes over his patient. “I shan’t bleed you.”

“No, that you won’t!” retorted Nicky, faint but indomitable.

“Until tomorrow,” finished Greenlaw grimly.

He then beckoned Elinor out of the room, gave her a few instructions, told her that as Nicky would in all probability sleep soundly now for several hours she might as well go back to her bed, and, after promising to return later in the day, took himself off. Nicky did indeed seem sleepy, so as soon as she had taken the precaution of locking the door into the room that gave access to the secret stair, Elinor retired to her own room again and once more went to bed.

It was long before she slept, however. Aside from his desperate behavior, the return of her mysterious visitor most seriously alarmed her. That he did indeed want something from Highnoons was now established, and since his conduct clearly indicated that he would stop at nothing to obtain it she was unable to view with the smallest equanimity a continued sojourn in the house. The scutter of a mouse across the floor made her jump nearly out of her skin, and she was kept awake for a long time by an uncontrollable anxiety to strain her ears on the chance of catching any alien noise in the house. Her dreams, when she did at last fall asleep, were troubled, and she arose in the morning feeling very little rested and considerably incensed with Carlyon for having placed her at Highnoons.

Nicky, whom she found sitting up in bed and partaking of a substantial breakfast, seemed to be little the worse for his adventure. Mrs. Barrow had fashioned a sling for his left arm and whenever he did not need the use of this arm he gratified her by slipping it into the sling. He too had been thinking over the night’s adventure, and he greeted Elinor with the pleasing suggestion that his assailant had been a French spy.

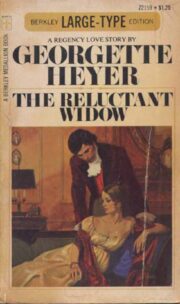

"The Reluctant Widow" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Reluctant Widow". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Reluctant Widow" друзьям в соцсетях.