‘I have not seen you at the Court before,’ he said.

‘It is not surprising since I am lately come,’ she answered.

‘And what think you of it?’

‘It is a sad Court in a way. The threat of the English invaders hangs over it still.’

‘Ah yes,’ he sighed. ‘But it has improved has it not? In the last two years there has been change.’

‘A slow change,’ said Agnès.

‘And you think it should be quicker?’

‘But of course, my lord.’

‘The King should bestir himself, you think?’

‘Aye, that he should. He should rid himself of ministers who impede him, and act for himself.’

‘You are not of the Court, but lately come, you say, yet you tell the King’s minsters how they should act.’

‘Not his ministers. But I think the King should rouse himself. He should take the governing of the country in hand. He should be a King in truth.’

‘Which he is not at the moment?’

‘As you said I am a simple girl from the country, but I listen, I think; and I know what has happened. We had a brief glory when the Maid came and drove the besiegers from Orléans and had the Dauphin made King at Rheims...and then...’

‘Yes, my lady, and then?’

‘Then it stopped.’

‘There were no more miracles, you mean. The Maid lost her powers and then the English burned her as a witch.’

‘They should never have been allowed to.’

‘Nay, you speak truth there. And do you think that is why God no longer seems on the side of the French?’

‘He is not on the side of the English either.’

‘In fact He has shut the gates of Heaven and is leaving us to our own devices.’

‘I think...’

‘Yes, my lady, what do you think?’

‘I think that God would help France again if France helped herself

She stood up.

‘So you are going now?’

‘Yes, I must return to my charges.’

‘Who are your charges?’

‘The children of the Duchess of Lorraine. Yolande and Margaret.’

‘So you are in that lady’s train. Shall you be in the gardens tomorrow?’

She looked at him steadily.

‘I would be here, if you wished it.’

‘That is gracious of you.’

She laughed then. ‘Nay, all would say it is gracious of you. I know who you are. Sire.’

He was amazed. She had not behaved as though in the presence of the King. And all the time she had known him!

She was quite unabashed by her own temerity. ‘I have known you long,’ she said. ‘I thought of you often...during the difficult days. I should have been very happy to have been at Rheims on the day they crowned you.’

‘You are a strange girl,’ he said. ‘What is your name?’

‘It is Agnès Sorel.’

‘Agnès Sorel,’ he repeated. ‘I have enjoyed our talk. I shall see you again.’

She saw him again. He was attracted by her. She was in the first place outstandingly beautiful, and in a serene way, quite different from the flamboyant beauties of his Court. She cared about the country. That was what amazed him. There was no sign of coquetry. She must have thought him extremely ugly, which he undoubtedly was, and old too, for he appeared to be older than his years and she was very young. He was astonished by how much she knew of the country’s affairs.

By the end of the second meeting he was more fascinated than he had been at the first. Her frank manner, her complete indifference to his royalty enchanted him. He could not stop looking at her. He discovered she was more beautiful every time he saw her. But chiefly he discovered a peace in her company which he had never known before.

He talked to the woman he admired more than any other. She was his mother-in-law Yolande of Anjou who was a frequent visitor at the Court and who had been one of his closest friends ever since he had known her. He was closer to her than to his wife. He was in fact glad that he had married Marie because the marriage had brought him Yolande.

‘Do you know the young girl who travelled in your daughter-in-law’s train? She is in charge of the little girls.’

‘Oh, Agnès, you mean. She’s a delightful creature is she not?’

He was relieved that his mother-in-law shared his views.

‘I find her so,’ he said.

‘You have made her acquaintance...personally then?’

‘Yes. But not as you might think. She is not the sort of girl for a quick encounter today and to be forgotten tomorrow.’

‘I would agree with that.’

‘Her conversation is amazing in one who has lived her life in the country.’

‘She has a bright intelligence and a rather unusual beauty.’

‘That was my opinion.’

‘Have you...plans concerning this girl?’

The King was silent.

‘I find myself thinking of her often but not...in the usual way.’

‘I see,’ said Yolande thoughtfully. She was thinking that it would be good for him to have a mistress of good reputation. If Charles were ever going to win the respect of his people he would have to change. He would have to develop confidence in himself; he would have to act more forcefully; he would have to be extricated from ministers whose one aim was to enrich themselves. He was fond of women; he listened to women. Yolande regarded that as a virtue. She believed that if Charles could be surrounded by wise people, if he could be aroused from his lethargy, if it could be brought home to him that he had the makings of a great monarch in him, he could become one.

She went on thoughtfully: ‘I think the girl would be an asset to our Court. She has a certain grace. I noticed it myself. She could become a member of Marie’s household. I will speak to her.’

‘As always you are my very good friend.’

‘Leave it to me,’ said Yolande.

It may have seemed strange, she ruminated, that she should introduce into her daughter’s household a young girl who was very likely destined to become the King’s mistress. But Yolande was far-seeing. How much better for the King to have one good woman to whom he was devoted than a succession of furtive fumblings with serving girls which was ruining his health in any case as well as undermining his dignity. Yolande looking into the future could see the day arrive when Charles could be a great King. She must therefore allow no obstacles to stand in his way. He needed guidance until he found the way he must go; and he would succeed, Yolande believed. She knew men; she knew how to govern; she herself had acted as Regent of Anjou for her eldest son Louis who was in Naples trying to keep hold of the crown there. In her wisdom she believed that Charles needed as many steadying influences as could be found. And it seemed to her that this beautiful and wise young girl could well be one of them. She could mould Agnès, become her friend. Charles was not the only one who sensed rare qualities in this girl. It was worth giving the matter a try.

Isabelle, realizing that no help could be obtained from the King, prepared to return to the palace in Nancy where her own mother was in charge.

When she went she left Agnès Sorel behind. Agnès had become Maid of Honour to the Queen of France.

Meanwhile René was finding a certain amount of enjoyment in captivity. He had never been one to care for battles. His position forced him into a situation which his inclination would have been to avoid if there had been a choice. Yolande had seen that he had been brought up to reverence the laws of chivalry, and these often made heavy demands on a man.

However, at Dijon, he had leisure and he was free of making war. The laws of chivalry demanded that he must be treated with the utmost respect which resulted in the fact that, strictly confined as he was, he was more of a guest at Dijon than a prisoner.

Although he was closely guarded he could go where he liked within the castle and he found pleasure in the chapel where there was a great deal of glass some of which had been decorated with exquisite paintings. René was a painter of some ability; he was also a poet and a musician; how often had he deplored his inability to devote himself to these activities which he loved. Now here was a chance. He had so much admired the paintings in the chapel that he would like to paint on glass himself. Glass was found for him and paints provided and in a short time René was passing the days of his captivity in a very pleasant fashion.

Time flew. He had completed a portrait of the late Duke John of Burgundy, who had been known as the Fearless; and so pleased was he with it that he did another of the Duke’s son, the present Duke Philip.

He then painted miniatures of other members of the family and looked forward to each day when he could continue with his work.

When he heard that the Duke of Burgundy had announced his intention of visiting Dijon he scarcely heard the news; he was so intent on getting the right texture for the hair of the subject of one of his paintings.

Duke Philip arrived and expecting to find an abject René of Anjou begging for his release was surprised to find the captive intent on his work.

The Duke looked at the painting. ‘Why it is beautiful,’ he said. ‘I had no idea you were an artist.’

‘Oh,’ said René modestly, ‘it passes the time.’

He talked of the way he mixed his paints and the subjects who pleased him most.

‘You seem to have found an agreeable way in which to spend your captivity,’ said the Duke.

‘An artist,’ explained René, ‘can never truly become the captive of anything but his own imagination.’

‘So an artist can be content wherever he is.’

‘While engaged in the act of creation most certainly.’

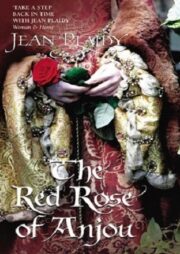

"The Red Rose of Anjou" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Rose of Anjou". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Rose of Anjou" друзьям в соцсетях.