Edmund’s brother Jasper is supposed to live a few miles away at Pembroke Castle, but he is rarely there. He is either at the royal court, trying to hold together the irritable accord between the York family and the king, in the interests of the peace of England, or he is with us. Whether he is riding out to visit the king, or coming home, his face grave with worry that the king has slipped into his trance again, he always manages to find a road that passes by Lamphey and to come for his dinner.

At dinner, my husband Edmund talks only to his brother Jasper. Neither of them say so much as one word to me, but I have to listen to the two of them worrying that Richard, Duke of York, will make a claim on the throne on his own account. He is advised by Richard Neville, the Earl of Warwick, and these two, Warwick and York, are men of too vast an ambition to obey a sleeping king. There are many who say that the country cannot even be safe in the hands of a regent, and if the king does not wake, then England cannot survive the dozen years before his son is old enough to rule. Someone will have to take the throne; we cannot be governed by a sleeping king and a baby.

“We can’t endure another long regency; we have to have a king,” Jasper says. “I wish to God you had married and bedded her years ago. At least we would be ahead of the game now.”

I flush and look down at my plate, heaped with overcooked and unrecognizable bits of game. They hunt better than they farm in Wales, and every meal brings some skinny bird or beast to the table in butchered portions. I long for fast days when we have only fish, and I impose extra fast days on myself to escape the sticky mess of dinner. Everyone stabs what they want with their dagger from a common plate, and sops up the gravy with a hunk of bread. They wipe their hands on their breeches, and their mouths on their coat cuffs. Even at the high table we are served our meat on trenchers of bread that are eaten up at the end of the meal. There are no plates laid on the table. Napkins are obviously too French; they count it a patriotic duty to wipe their mouths on their sleeves, and they all bring their own spoons as if they were heirlooms, tucked inside their boots.

I take a little piece of meat and nibble at it. The smell of grease turns my stomach. Now they are talking, in front of me as if I were deaf, of my fertility and the possibility that if the queen is driven from England, or her baby dies, then my son will be one of the king’s likely heirs.

“You think the queen will let that happen? You think Margaret of Anjou won’t fight for England? She knows her duty better than that,” Edmund says with a laugh. “There are even those who say that she was too determined to be stopped by a sleeping husband. They say she got the baby without the king. Some say she got a stable boy to mount her rather than leave the royal cradle empty and her husband dreaming.”

I put my hands to my hot cheeks. This is unbearable, but nobody notices my discomfort.

“Not another word,” Jasper says flatly. “She is a great lady, and I fear for her and her child. You get an heir for yourself, and don’t repeat gossip to me. The confidence of York with his quiver of four boys grows every day. We need to show them there is a true Lancaster heir-in-waiting; we need to keep their ambitions down. The Staffords and the Hollands have heirs already. Where’s the Tudor-Beaufort boy?”

Edmund laughs shortly and reaches for more wine. “I try every night,” he says. “Trust me. I don’t skimp my duty. She may be little more than a child herself, with no liking for the act, but I do what I have to.”

For the first time, Jasper glances over to me, as if he is wondering what I make of this bleak description of married life. I meet his gaze blankly with my teeth gritted. I don’t want his sympathy. This is my martyrdom. Marriage to his brother in this peasant palace in horrible Wales is my martyrdom; I offer it up, and I know that God will reward me.

Edmund tells his brother nothing more than the truth. Every single night of our life, he comes to my room, slightly unsteady from the wine at dinner that he throws down his throat like a sot. Every night, he gets into bed beside me, and takes a handful of my nightgown as if it were not the finest Valenciennes lace hemmed by my little-girl stitches, and holds it aside so he can push himself against me. Every night I grit my teeth and say not one word of protest, not even a whimper of pain, as he takes me without kindness or courtesy; and every night, moments later, he gets up from my bed and throws on his gown and goes without a word of thanks or farewell. I say nothing, not one word, from beginning to end, and neither does he. If it were lawful for a woman to hate her husband, I would hate him as a rapist. But hatred would make the baby malformed, so I make sure I do not hate him, not even in secret. Instead, I slide from the bed the minute he has gone and kneel at the foot of it, still smelling his rancid sweat, still feeling the burning pain between my legs, and I pray to Our Lady who had the good fortune to be spared all this by the kindly visit of the bodiless Holy Ghost. I pray to Her to forgive Edmund Tudor for being such a torturer to me, her child, especially favored by God. I, who am without sin, and certainly without lust. Months into marriage I am as far away from desire as I was when I was a little girl; and it seems to me that there is nothing more likely to cure a woman of lust than marriage. Now I understand what the saint meant when he said that it was better to marry than to burn. In my experience, if you marry, you certainly won’t burn.

SUMMER 1456

One long year of loneliness and disgust and pain, and now I have another burden to bear. Edmund’s old nursemaid becomes so impatient for another Tudor boy that she comes to me every month to ask if I am bleeding, as if I were a favorite mare at stud. She is longing for me to say no, for then she can count on her fat old fingers and see that her precious boy has done his duty. For months I can disappoint her and see her wizened old face fall, but at the end of June I can tell her that I have not bled, and she kneels down in my own privy chamber and thanks God and the Virgin Mary that the House of Tudor will have an heir and that England is saved for the House of Lancaster.

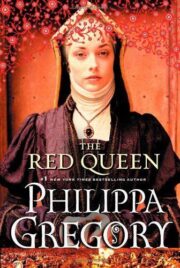

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.