“Does Richard know of Henry’s plans?” I ask, one evening before he is utterly sodden with the wine that my cellars are forced to yield to him.

“He has spies all over Henry’s little court, of course,” Stanley replies. “And a spy network which passes news from one end of the country to the other. A fishing boat could not land in Penzance now without Richard learning of it the next day. But your son has grown into a cautious and clever young man. As far as I know, he keeps his counsel and makes plans only with his uncle Jasper. He takes no one else into his confidence; Richard never refers to any intelligence from Brittany that is not obvious news. It is clear that they will equip ships and come again, as soon as they are able. But they will be set back by their failure last year. They have lost their sponsor a small fortune; perhaps he will not want to risk another fleet for them. Most people think the Duke of Brittany will have to give them up and hand them over to France. Once in the power of the French king they could be lost, they could be made. More than that, Richard doesn’t know.”

I nod.

“Did you hear that Thomas Grey, Elizabeth Woodville’s son, ran from your son’s court and was trying to get home to England?”

“No!” I am shocked. “Why would he do that? Why would he want to leave Henry?”

My husband smiles at me over his wineglass. “It seems that his mother commanded him to come home and make his peace with Richard, just as she and the girls have done. Doesn’t look as if she believes that Richard killed the boys, does it? Doesn’t look like she thinks Henry is a horse worth backing anymore. Why else would she hope for a full reconciliation with the king? Looks like she wants to sever her ties with Henry Tudor.”

“Who knows what she thinks?” I say irritably. “She is a fickle woman with no loyalty to anyone but her own interest. And no sense.”

“Your son Henry Tudor caught Thomas Grey on the road and took him back again,” my husband remarks. “So now, they are holding him as a prisoner. He is more a hostage than a supporter to their court. It doesn’t bode well for the betrothal of your son and the princess though, does it? I assume she will reject the betrothal, just as her half brother has denied his fealty. That must hurt your cause, as well as humiliating Henry. Looks like the House of York has turned against you.”

“She can’t deny her betrothal,” I snap. “Her mother swore to it, and so did I. And Henry has sworn to it before God in the cathedral at Rennes. She will have to get a dispensation from the pope himself if she wants to get out of it. And anyway, why would she want to get out of it?”

My husband’s smile grows broader. “She has a suitor,” he says quietly.

“She has no right to have a suitor; she is betrothed to my son.”

“Yes, but she has all the same.”

“Some grubby page, I daresay.”

He chuckles as if at a private jest. “Oh no. Not exactly.”

“No nobleman would stoop to marry her. She is declared a bastard, is publicly betrothed to my son, and her uncle has promised her only a moderate dowry. Why would anyone want her? She is shamed three times over.”

“For her beauty? She is radiant, you know. And her charm-she has the most delightful smile, you really can’t look away from her. And she has a merry heart, and a pure soul. She is a lovely girl, a real princess in every way. It is as if she came out of sanctuary and simply came alive in the world. I think he is just simply in love with her.”

“Who is this fool?”

He glows with amusement. “Her suitor, the one I am telling you about.”

“So who is this lovestruck idiot?”

“King Richard himself.”

For a moment I am silenced. I cannot imagine such wickedness, such a ruling of lust. “He is her uncle!”

“They could get a papal dispensation.”

“He is married.”

“You said yourself that Queen Anne is infertile and unlikely to make old bones. He could ask her to step aside; it wouldn’t be unreasonable. He needs another heir-his own son is ill again. He needs another boy to secure his line, and the Riverses are famously fertile. Think of Queen Elizabeth’s performance in the marriage bed of England!”

My sour face tells him I am thinking of it. “She is young enough to be his daughter!”

“As you yourself know, that is hardly an obstacle, but in any case, it isn’t true. There are only fourteen years between them.”

“He is the murderer of her brothers, and the destruction of her house!”

“Now you, of all people, know that is not true. Not even the common people believe that Richard killed the boys, now that the queen is reconciled with him and living in the country, and the princesses are at his court.”

I rise from the table; I am so disturbed I forget even to say grace. “He can’t intend to marry her; he must mean only to seduce her and shame her, to make her unfit for Henry.”

“Unfit for Henry!” He laughs aloud. “As though Henry is in a position to choose! As though he is such a catch himself! As though you have not tied him to the princess just as you say she is tied to him.”

“Richard will make her his whore to shame her and her whole family.”

“I don’t think so. I think he loves her, truly. I think King Richard is in love with Princess Elizabeth, and it is the first time in his life he has ever been in love. You see him look at her, and he seems just filled with wonder. It is an extraordinary thing to see, as if he had discovered the meaning of life in her. It is as if she were his white rose, truly.”

“And she?” I spit. “Does she show proper distance? Is she a princess in her self-respect? She should think only of her purity and her virtue, if she is a princess and hopes to be queen.”

“She adores him,” he says simply. “It shows. She lights up when he comes in the room, and when she dances she throws him a little private smile and he can’t take his eyes off her. They are a couple in love, and anyone but a fool would see it is simply that, nothing more-and certainly nothing less.”

“Then she is no better than a whore,” I say, going from the room as I cannot bear to hear another word. “And I shall write to her mother and give her my sympathy, and my prayers for her daughter who has fallen into shame. But I cannot be surprised at the two of them. The mother is a whore; and it turns out that the daughter is no better.”

I close the door on his mocking laughter, and I find to my surprise that I am shaking, and that there are tears on my cheeks.

Next day, a messenger comes from the court for my husband, and he does not have the courtesy to send it on to me, so I have to go down to the stable yard, like a maid-in-waiting, to find him calling out his men and ordering them into the saddle. “What is happening?”

“I am going back to court. I have had a message.”

“I was waiting for you to send the messenger on to me.”

“It was my business. Not yours.”

I close my lips on an undutiful retort. Since he was granted my lands and my fortune he has not hesitated to behave as my master. I submit to his rudeness with the grace from Our Lady, and I know that She will make note of it.

“Husband, will you tell me please if there is danger or trouble in the land? I must be allowed an answer to that.”

“There is loss,” he says briefly. “There is loss in the land. King Richard’s son, the little Prince Edward, is dead.”

“God rest his soul,” I say piously, while my head spins with excitement.

“Amen. And so I must go back to court. We will be in mourning. It will strike Richard hard, I don’t doubt. Only one child ever born to them, and now he is gone.”

I nod. Now there is only Richard himself between my boy and the throne; there is no other heir but my son. We spoke of the heartbeats that blocked my son’s path to the throne, and now all the boys of York are dead. It is time for the Lancaster boy. “So Richard has no heir,” I breathe. “We serve a childless king.”

My husband’s dark eyes are on my face; he smiles as if he is amused by my ambition. “Unless he marries the York princess,” he teases me gently. “And they are fertile stock, remember. Her mother gave birth almost every year. Say Elizabeth of York gives him a quiver full of princes and the support of the Rivers family, and the love of the York affinity? He has no son from Anne-what should now stop him putting her aside? She might give him a divorce at once, and retire to a nunnery.”

“Why don’t you go back to court?” I ask, too angry to mind my tongue. “You go back to your faithless master and his York whore.”

“I will go.” He swings up into the saddle. “But I will leave you with Ned Parton over there.” He gestures to a young man standing beside a big black horse. “He is my messenger. He speaks three languages, including Breton, should you want to send him to Brittany. He has a safe pass through this country, through France and Flanders, signed by me as Constable of England. You can trust him to send messages to anyone you like, and no one can stop him or take them from him. King Richard may appear to be my master, but I don’t forget your son and his ambitions, and he is only one step from the throne this morning, and my beloved stepson as always.”

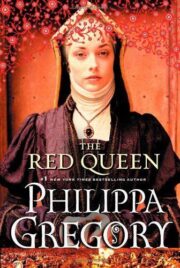

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.