SPRING 1484

All the winter and all of the spring, I meditate on their wrongdoing, and I find I am glad that the queen is still locked in sanctuary. While I am imprisoned in my own home, I think of her, trapped in the gloomy crypt beside the river, facing her defeat in the darkness. But then, in the spring, I have a letter from my husband.

King Richard and Elizabeth Woodville have come to an accord. She has accepted the writ of Parliament that she was never married to the late king, and King Richard has sworn that she and her daughters will be safe to come out of sanctuary. She is going into the keeping of John Nesfield and will live in his manor at Heytesbury in Wiltshire, and the girls are to go to court and serve as ladies-in-waiting to Queen Anne until marriages can be arranged for them. He knows that your son declared his betrothal to the Princess Elizabeth, but you and your son are disregarded. Elizabeth Woodville seems to have accepted defeat, and she seems reconciled to the deaths of her two sons. She never speaks of either.

And-at this time of reconciliation-I ordered a private search of the Tower so that the bodies of the princes might be found and their deaths blamed on the Duke of Buckingham (and not on you), but the stair where you said they were buried has not been disturbed and there is no sign of them. I have let it be spread about that their bodies were buried and then taken away by a remorseful priest and laid to rest in the deepest waters of the Thames-appropriate, I thought, for sons of the House of Rivers. This seems to conclude the story as well as any other version, and no one has contradicted this with any more inconvenient details. Your three murderers, if they did the deed at all, are staying quiet.

I shall come to visit you shortly-the court is joyous in its triumph in the fine weather and the newly released Princess Elizabeth of York is the little queen of the court. She is the most charming girl, as beautiful as her mother was; half the court is besotted with her, and she will certainly be married very well within the year. A girl so exquisite will not be hard to match.

Stanley

This letter irritates me so intensely that I cannot even pray for the rest of the day. I have to take my horse and ride to the end of the parkland and all around the perimeter-the limit of my freedom-hardly seeing the bobbing yellow heads of the daffodils, nor the young lambs in the fields, before I can recover my temper. The suggestion that the princes are not dead and buried, which undoubtedly they are, and his further layering of lies with his exhumation and water burial in the Thames story-which merely creates further questions-would be enough to enrage me, but to couple it with news of the freedom of Queen Elizabeth and the triumph of her daughter at the court of the man who should be their enemy till death: this shocks me to the core.

How can the queen bring herself to forge an agreement with the man she should accuse of killing her sons? It is a mystery to me, an abomination. And how can that girl go dancing round her uncle’s court as if he were not the murderer of her brothers and the jailer of her girlhood? I cannot comprehend it. The queen is, as she always has been, steeped in vanity and lives only for her own comfort and pleasure. No surprise to me at all that she should settle for a handsome manor and-no doubt-a good pension and a pleasant livelihood. She cannot be grieving for her boys at all, if she will take her freedom from the hands of their murderer.

Heytesbury Manor indeed! I know that house, and she will be luxuriously comfortable there, and I don’t doubt that John Nesfield will allow her to order anything she wants. Men always fall over themselves to oblige Elizabeth Woodville because they are fools for a pretty face, and though she led a rebellion in which good men died and which cost me everything; it seems that she is to get off scot-free.

And her daughter must be a thousand times worse, to accept freedom under these terms and to go to court and order fine dresses, and serve as lady-in-waiting to a usurping queen, sitting on the throne that had been her mother’s! Words fail me, my prayers fail me, I am stunned into silence by the falseness and the vanity of the York queen and the York princess, and the only thing I can think of is how can I punish them for getting free, when I am ruined and imprisoned? It cannot be right, after all we have gone through, that the York queen once again comes out of danger and sanctuary and lives in a beautiful house in the heart of England, raises her daughters, and sees them married well among her friends and neighbors. It cannot be right that the York princess is a favorite at the court, the darling of her uncle, the sweetheart of the people, and I thrown down. God cannot really want these women to lead peaceful, happy lives while my son is in exile. It cannot be His will. He must want justice, He must want to see them punished, He must want to see their downfall. He must long for the burning of the brand. He must desire the scent of the smoke of their sacrifice. And, God knows, I would be His willing instrument if He would just put the weapon in my obedient hand.

APRIL 1484

My husband comes to visit me as the king is on a spring progress, traveling to Nottingham, where he will make his headquarters this year, readying for the invasion of my son that he knows must come this year, or the next, or the year after. Thomas Stanley rides out on my lands every day, as greedy for the chase as if it were his own game to kill-and then I remember that it is. Everything belongs to him now. He eats well at night and drinks deeply of the rare wines laid down in the cellar by Henry Stafford, for me and for my son, and which now belong to him. I thank God that I am not attached to worldly goods, as other women are, or I would look at the march of bottles along the table with deep resentment. But I thank Our Lady; my mind is fixed on the will of God and the success of my son.

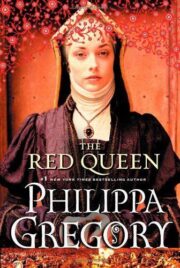

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.